Argentine Political Expressionist Artist Luis Felipe “Yuyo” Noé has died, and with him goes a central figure in 20th-century Argentine art. He was, without a doubt, a foundational artist in the history of local art: co-founder of the Nueva Figuración movement, a theorist of chaos as method and aesthetic, and an acute thinker of Argentina’s political and existential decomposition. But he was also a violent, misogynistic figure, aggressive toward his peers—particularly toward the women who dared to challenge his authority.

Argentine legendary artist Yuyo Noé died and the cultural sector mourns him but he was a violent, misogynistic figure, aggressive toward his peers—particularly toward the women who dared to challenge his authority.

Tweet

In this sense, his death should not serve as an excuse for sanctification. To pay tribute is not to absolve. And criticism does not diminish a legacy—it makes it more legible.

Bohemian masculinity as a form of exclusion

Yuyo Noé embodied a distinctly porteño form of cultural masculinity: exalted, chaotic, authoritarian in its disorder. The archetype of the “male artist” who turns excess into a virtue, ego into politics, and mistreatment into performance. Within this model, women were systematically sidelined—if not outright abused. The case of Martha Traba is emblematic. She lucidly questioned Noé’s self-referentiality, his aestheticization of chaos as an excuse to avoid political engagement, and his lack of interest in the material conditions of artistic production in Latin America. Noé dismissed her with sarcasm: “Traba had a view that was too ideological; she lacked artistic sensitivity. She wanted to do sociology with paintings.” A classic move from the patriarchal playbook: reduce the critical woman to a killjoy who just doesn’t “get” pure art.

Argentine-Colombian art critic Martha Traba lucidly questioned Noé’s self-referentiality, his aestheticization of chaos as an excuse to avoid political engagement and he insulted her.

Tweet

This gesture of delegitimization repeated itself throughout his career. He was known for his outbursts, for public tantrums, for mistreating female colleagues in institutional and academic settings. He was celebrated for “saying what he thinks,” when in fact he exercised class and gender violence with total impunity. That symbolic violence isn’t an anecdote—it’s part of the system of consecration that sustained him.

The work: between chaos and over-legitimation

Noé’s first major cycle—Introducción a la esperanza (1963), created with Deira, Macció, and De la Vega—opened new possibilities for Argentine painting. It blended the grotesque, the political, and the gestural in a language that dismantled modernist narrative without lapsing into cynicism. Yet even then, a recurring gesture emerges: the aestheticization of chaos as a signature style, a kind of “trademark” that disguises formulaic repetition.

In Argentina 78, for example, his reading of the dictatorship and the World Cup is rendered through overloaded iconography—a baroque painting style that seeks to denounce horror while never relinquishing visual spectacle. The work reads more as a document of personal anguish than as any effective political intervention. The same is true of his Entropías and Revuélquese y viva series, where chaos becomes a style, a form of decoration, rather than a political tool.

Noé’s work reads more as a document of personal anguish than as any effective political intervention.

Tweet

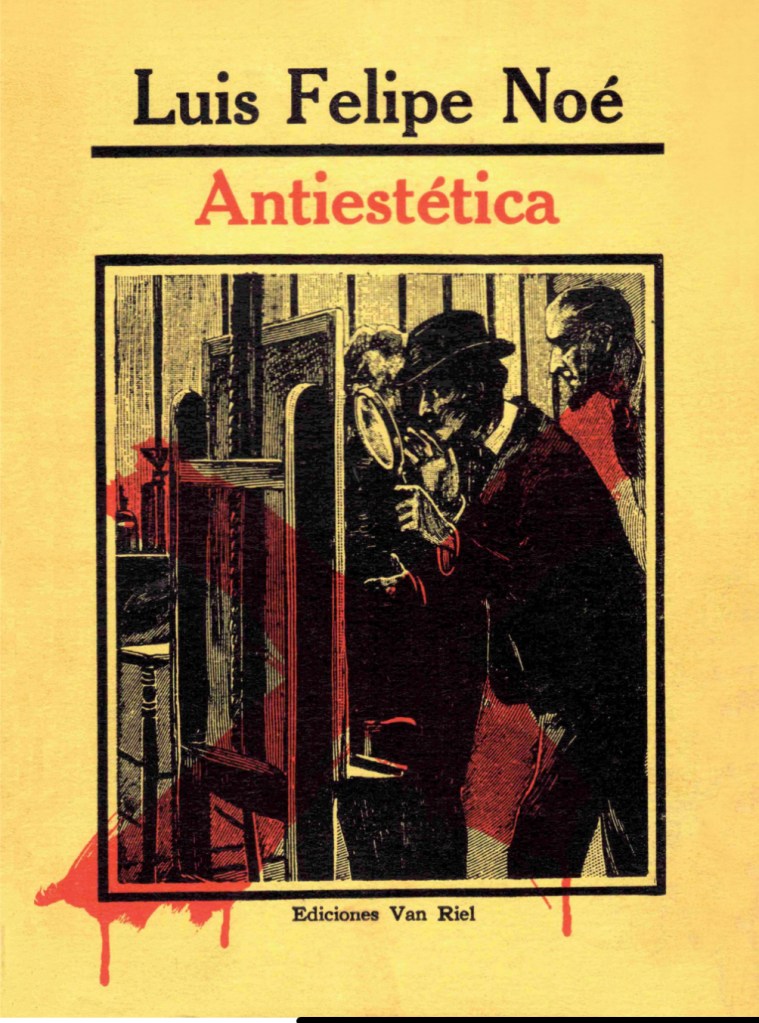

Noé was able to theorize his own work intelligently, particularly in books like Antiestética (1965) and El arte entre la tecnología y la rebelión (1991). But even there, his thinking revolves around a masculine authorial subjectivity presented as universal. Women are largely absent: as artists, as theorists, as interlocutors.

Family legacy: from chaos to sadism

This notion of creation—as the violent imposition of a vision—finds a direct echo in the work of his son, Gaspar Noé. In Irreversible (2002), the director turns a woman’s suffering (the rape of Monica Bellucci) into a technical spectacle: long take, spinning camera, reversed narrative time. Jonathan Romney wrote in The Independent: “Irreversible flirts with the aestheticization of rape, presenting violence against women not to critique it but to fetishize it.” The result isn’t a denunciation but rather sadism dressed up as philosophy. A clear genealogy: from painterly chaos to cinematic cruelty.

The present: women defending the patriarch

But perhaps the most telling symptom isn’t in the past, but in the present. After Noé’s death, many women artists and curators rushed to express unconditional admiration. Diana Aisenberg wrote that “Yuyo was a father to us all,” and in her elegy failed to mention a single controversy or exclusion. María Teresa Constantin remembered him on Instagram as “the last great Argentine artist,” adding that “artists should be judged by their work, not their character.” Even Marina de Caro, in a letter published in Otra Parte, spoke of his “infinite generosity” without once interrogating the role he played in sustaining an exclusionary canon.

Mostly female artists have been co-opted by a prestige system that rewards loyalty to the symbolic father like Noé. Now, they mourn him with filial terminology.

Tweet

These defenses are not innocent. They reflect how many women have been co-opted by a prestige system that rewards loyalty to the symbolic father. Noé—like so many others—was the patriarch who let them in, in exchange for silence. The canon is not upheld by men alone: it is also maintained by women who choose exceptionalism over rupture.

Noé was the patriarch who let these crying female artists let in, in exchange for silence. The canon is not upheld by men alone: it is also maintained by women who choose exceptionalism over rupture.

Tweet

Critical homage

To honor Noé means not buying into the mythology of the chaotic genius. It means recognizing his place without romanticizing his violence. It means asking how many women artists were written out of the story while he was elevated to sacred figurehood. And perhaps it’s time to begin crafting an Argentine art history that needs neither fathers nor martyrs—but memory, dissent, and new ways of making.

Deja una respuesta