To Read It in English Scroll Down

Si querés leer la nota en Clarín sobre mi entrevista a Martí sobre haters y blogueros premium, hacé click aquí/ If you want to read the Clarín article about my interview with Martí on haters and premium bloggers, click here.

Ayer no escribí. Fui invitado por JP, el marido de Agustina, por Agustina misma y por su hijo —un adolescente luminoso, brillante, de esos que todavía creen que la inteligencia puede ser un lugar de libertad— a ver One Battle After Another en el Odeon de Dún Laoghaire.

Tweet

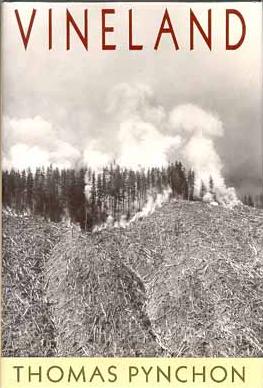

Ayer no escribí. Fui invitado por JP, el marido de Agustina, por Agustina misma y por su hijo —un adolescente luminoso, brillante, de esos que todavía creen que la inteligencia puede ser un lugar de libertad— a ver One Battle After Another en el Odeon de Dún Laoghaire. Dirigida por Paul Thomas Anderson, quien adapta libremente elementos de Vineland de Thomas Pynchon, la película narra cómo un grupo de antiguos revolucionarios debe reunirse cuando, dieciséis años después, reaparece un enemigo que los obliga a rescatar a la hija de uno de sus miembros. Leonardo DiCaprio, Sean Penn, Teyana Taylor, Benicio del Toro y Regina Hall integran su elenco principal.

Caminamos los cuatro hasta el cine. Ayer no escribí porque elegí aceptar esa invitación. Y en esa elección hubo algo que más tarde entendería como una lección sobre el tiempo: dejar que el día se pliegue, que abandone su productividad forzada. Que exista sin prometer. En Buenos Aires o en Londres, cada desplazamiento está medido por una meta; en Dublín, en cambio, uno puede caminar hacia una película como si caminara hacia una pausa. Dún Laoghaire tiene ese aire de elegancia que sobrevivió a la pobreza para invertirla, una mezcla de fin de siglo y estacionamiento costero que me resulta familiar, aunque en Hastings esa familiaridad se invierta, como si Inglaterra misma funcionara al revés. A mitad del camino, JP me señaló un edificio de ladrillo y dijo que allí había vivido un músico conocido, “un tipo que se negaba a terminar sus canciones”. Le respondí que eso me parecía un gesto político. Se rió.

Entramos al Odeon. El vestíbulo estaba casi vacío. Compramos pochoclos que ninguno terminó. El hijo de JP —cuya mente navega entre Virgilio y Godard— me explicó, con entusiasmo contagioso, cómo One Battle After Another juega con el mito de la revolución como repetición infinita, con ese código que DiCaprio olvida al hacer el llamado que activaría al grupo revolucionario y sus estrategias de cuidado mutuo. En la película, el olvido como negación y la elasticidad del tiempo como disenso son el eje del argumento. Lo escuché y pensé que ese joven, tal vez sin saberlo, ya había formulado el corazón de lo que Édouard Glissant teorizaba: que la historia no es lineal sino archipiélago, que cada generación hereda el olvido como un modo de empezar de nuevo.

One Battle After Another juega con el mito de la revolución como repetición infinita, con ese código que DiCaprio olvida al hacer el llamado que activaría al grupo revolucionario y sus estrategias de cuidado mutuo. El olvido como negación y la elasticidad del tiempo como disenso son el eje del argumento.

Tweet

La película nos dejó en silencio. Caminamos de vuelta por la costa, los cuatro, con el mar a la izquierda y las luces de los barcos temblando como recuerdos que todavía no se deciden a desaparecer. Hablamos poco. JP dijo que el filme le había recordado ciertas revueltas de los ochenta, “cuando aún se creía que cambiar el sistema era posible”. Su hijo contestó que quizá el problema no es el sistema, sino el calendario: seguimos midiendo el cambio con relojes viejos. Yo no dije nada. Pensaba que ese intercambio, tan breve, valía más que cualquier conversación sobre arte contemporáneo que hubiera tenido en los últimos meses. Luego Agustina comentó que la verdad nunca está en el ahora, al menos para cierta gente. Nulla veritas in nunc. Qué es escribir, si no eso: estar presente en una escena sin intervenir, registrar el ritmo con que el tiempo se desordena.

Luego Agustina comentó que la verdad nunca está en el ahora, al menos para cierta gente. Nulla veritas in nunc. Qué es escribir, si no eso: estar presente en una escena sin intervenir, registrar el ritmo con que el tiempo se desordena.

Tweet

Lo que Thomas Pynchon nos enseña, filtrado por la película de Anderson, es lo productivo del resquebrajamiento de la cronología. Cuando llegamos a la casa, me quedé pensando en la figura de la hija de la guerrillera —interpretada por Willa Ferguson— que repite el mandato genético de la revolución, la posibilidad de un cambio que no rompe el tiempo sino que lo hace tambalear. Esa herencia es problemática, no por revolucionaria sino por potencialmente eugenésica. En la Argentina kirchnerista tuvimos una élite moral marcada por la sangre de los caídos y su descendencia. Tal vez el futuro del arte esté ahí: en quienes entienden que el presente no necesita héroes ni linajes morales fundados por héroes, sino interrupciones de esas herencias. Quizá eso sea lo que Glissant quiso decir: la historia del mundo moderno impuso una cronología lineal y colonial que convierte el tiempo en instrumento de dominación. Frente a eso, propone una poética de la relación, donde el tiempo se fragmenta y se vuelve archipielágico: no progresa, sino que se entrelaza, se repite y se reinventa desde la memoria.

Tal vez el futuro del arte esté ahí: en quienes entienden que el presente no necesita héroes ni linajes morales fundados por héroes, sino interrupciones de esas herencias. La historia impuso una cronología lineal y colonial que convierte el tiempo en instrumento de dominación.

Tweet

El bucle y la memoria: de Lucas Martí a Pynchon

Hay una frase en la canción de Lucas Martí —esa que se repite como una plegaria: “Olvidándonos, olvidándonos. Todos desearíamos empezar de nuevo, ser hombres de nuevo, ser hombres más nuevos.”— que me persigue desde que la escuché. No es sólo el eco de una culpa colectiva o de un deseo de purificación; es algo más profundo: la conciencia de que el tiempo del arte y el tiempo del poder ya no coinciden. Martí no busca una redención. Busca un ritmo que se sale de la cronología.

Lucas Martí en su Políticamente de izquierdas, aristocráticamente de derechas no busca una redención. Busca un ritmo que se sale de la cronología.

Tweet

En su nuevo disco, Políticamente de izquierdas, aristocráticamente de derechas, hay un tono que no pertenece a la ironía habitual del pop argentino: un cansancio lúcido, una percepción de que el presente se ha vuelto un campo minado de repeticiones. “Toca castigar al mundo, lo dejamos para vos”, canta, y la frase funciona como diagnóstico de época. El castigo se privatizó. Cada uno administra el suyo. Lo que en el siglo XX eran utopías colectivas se volvió una psicología de la autodestrucción. La música de Martí —como antes la literatura de Pynchon— no describe esa transformación, la encarna: repite para desgastar, canta para producir grietas en el tiempo.

Thomas Pynchon, ese escritor invisible que desde los años sesenta convirtió la paranoia en método literario, entendió antes que nadie que el poder moderno no se limita a dominar los cuerpos, sino el flujo temporal. En novelas como Gravity’s Rainbow o Vineland, el pasado no desaparece: se configura como simulacro, como parodia o como trauma que reaparece en otra frecuencia. En Vineland —publicada en 1990—, el sueño de la revolución norteamericana de los setenta se encuentra con la maquinaria mediática de la era Reagan. La vigilancia de los 80s reemplaza al ideal, la memoria se mercantiliza y los antiguos militantes se descubren viviendo dentro del espectáculo que juraron destruir. Pynchon convierte esa coexistencia de tiempos —la utopía y su ruina— en su materia narrativa. Vineland no avanza; circula. Los personajes orbitan alrededor de un pasado que no se deja clausurar. El resultado es una escritura en loop, donde cada intento de recordar se transforma en otra forma de olvido. Es un mundo donde el archivo sustituye a la experiencia, donde la revolución sobrevive como imagen.

Lucas Martí, en su disco, hace algo similar pero desde otro registro. La repetición no es aquí un artificio posmoderno, sino un gesto de resistencia. En una época que exige novedad constante, repetir es una forma de negarse al mandato de la productividad. Su música, con esas capas de loops y coros que se disuelven, trabaja como una memoria que se rehúsa a avanzar. Ahí radica su potencia: el pop no como superficie ligera, sino como experimento temporal. Si Pynchon escribió Vineland para mostrar cómo la televisión y la cultura del espectáculo habían convertido la rebeldía en programación, Martí responde desde otro lado: desde el agotamiento de esa programación. Canta desde los restos. Donde Pynchon diagnosticaba la colonización del tiempo, Martí la padece como experiencia íntima. Sus canciones no buscan destruir el orden, sino habitar su fatiga.

i Pynchon escribió Vineland para mostrar cómo la televisión y la cultura del espectáculo habían convertido la rebeldía en programación, Martí responde desde otro lado: desde el agotamiento de esa programación. Canta desde los restos.

Tweet

Ese cansancio estetizado tiene algo político. Cuando Glissant habla de romper el tiempo lineal, no se refiere a detener el progreso, sino a liberarlo del dominio colonial del reloj. Martí, sin saberlo, comparte esa intuición: sus letras se mueven en una temporalidad que no quiere llegar a ninguna parte. De hecho, el verbo que más aparece en el disco es “olvidar”. Y olvidar, en su caso, no es rendición: es un modo de salir del régimen de la memoria oficial, esa que clasifica, archiva y castiga.

Escuchando el disco en Dublín, la conexión con Pynchon me resultó inevitable. Vineland describe una América que intentó borrar su propio pasado revolucionario y terminó convertida en caricatura de sí misma. El disco de Martí podría ser la banda sonora de ese proceso: la Argentina cultural de los últimos años, donde el arte oficial se confunde con el discurso policial del orden, repite la misma estructura. El castigo como forma de gobierno, la amnesia como política de Estado, la ironía como refugio. Lo interesante es que ni Pynchon ni Martí se instalan en la denuncia. No hay moral en sus obras. Hay estructura. Ambos proponen una ética del desajuste: vivir en un presente donde los tiempos no se alinean, donde el pasado no ofrece guía y el futuro no promete nada. Es la condición archipiélago de Glissant, pero traducida a la cultura pop y a la narrativa del siglo XXI. En ese sentido, la pregunta ya no es “¿dónde está el arte?”, sino cuándo se produce una grieta en la cronología que el poder impone. Cuándo una canción, una novela o incluso una escena en la calle logran torcer el tiempo y suspender, por un segundo, la obediencia. Martí canta esa suspensión; Pynchon la escribe; y en ambos casos, la revolución no aparece como evento, sino como interrupción.

Lo interesante es que ni Pynchon ni Martí se instalan en la denuncia. No hay moral en sus obras. Hay estructura. Ambos proponen una ética del desajuste: vivir en un presente donde los tiempos no se alinean, donde el pasado no ofrece guía y el futuro no promete nada

Tweet

Mientras caminaba anoche por Dún Laoghaire, pensé que tal vez esa era la verdadera herencia estética del siglo XX: haber descubierto que toda forma de libertad depende de un pequeño acto de asincronía. De salirse del ritmo. Dejar que el tiempo se vuelva irregular. En esa irregularidad, Martí y Pynchon se encuentran —el músico y el novelista, el pop y la paranoia—, ambos obsesionados con lo mismo: cómo seguir vivos en una época que nos exige avanzar cuando lo más urgente es detenerse.

El arte del castigo: Amoedo, Showgirls y la cronología del poder

Si en Martí y en Pynchon el tiempo se fractura, en el arte oficial argentino se vuelve norma. Esa es la diferencia central. Lo que para ellos es interrupción, para el sistema del arte es restaurador. Su función no es pensar el tiempo, sino administrarlo.

Lo vi con claridad cuando escribí sobre Ama Amoedo y la performance policial en la charity a beneficio del hospital Churruca, hospital de la Policia Federal. Aquello que se presentaba como filantropía o como gesto curatorial se revelaba como una maquinaria de orden, como amenaza. En el arte institucional argentino —el de las fundaciones, los museos con sponsors, los programas de arte y salud, la cultura corporativa de la corrección— el tiempo no se detiene: circula al servicio del castigo. La estética del orden reemplaza a la pregunta por la libertad.

En esa puesta en escena, Amoedo aparece como figura casi teológica: la que limpia la mancha, la que restituye la pureza perdida. Su misión no es crear, sino sostener la continuidad de un relato moral. Por eso su obra y su política filantrópica se articulan con lo que Foucault llamaba “el poder pastoral”: un poder que no necesita reprimir, sino que cura y protege mientras clasifica. El museo, la fundación, la bienal funcionan como templos donde el tiempo se ordena y las desviaciones se diagnostican.

En su fund raising, Amoedo aparece como figura casi teológica: la que restituye la pureza perdida. Su misión no es crear, sino sostener la continuidad moral. Por eso su obra filantrópica es pastoral: no necesita reprimir, sino que cura y protege mientras clasifica.

Tweet

Esa operación —la del arte como administración de los cuerpos y las emociones— no es nueva. Pero en el contexto actual, después de décadas de neoliberalismo estético, adquiere una sofisticación casi quirúrgica: ya no se trata de censurar la disidencia, sino de absorberla, estetizarla, volverla exhibible. Todo se transforma en programa educativo o proyecto inclusivo. El dolor se vuelve experiencia, la violencia se convierte en performance, y el tiempo, otra vez, se cierra sobre sí mismo.

Por eso me interesaba, al escribir sobre The Last Show Girl y la figura de Pamela Anderson, ese contraste radical: la película —ese monumento a la vulgaridad y al deseo— no teme el exceso. Es una forma de desobediencia temporal. Lo que el arte oficial reprime en nombre de la elegancia o la justicia social, el pop lo exhibe como verdad. Anderson, en su última encarnación como The Last Show Girl, encarna el fracaso con dignidad, no con culpa. Y ahí aparece algo que conecta con Martí y con Pynchon: la ética del desajuste.

Anderson, en su última encarnación como The Last Show Girl, encarna el fracaso con dignidad, no con culpa. Y ahí aparece algo que conecta con Martí y con Pynchon: la ética del desajuste.

Tweet

El poder necesita linealidad porque su lógica es la de la causa y el efecto: primero el delito, luego el castigo; primero el trauma, luego la curación. Esa es la narrativa de Amoedo, pero también la del Estado. Lo que Glissant, Pynchon o Martí interrumpen es precisamente esa causalidad. En sus universos, las causas no producen efectos predecibles: producen resonancias, retornos, desvíos. El tiempo no es una línea, sino un delta.

En el arte argentino contemporáneo, en cambio, domina el tiempo circular del prestigio. Cada gesto vuelve a su origen institucional. La radicalidad se homologa, la crítica se financia. Los artistas que realmente desajustan —que exponen las heridas del sistema sin maquillarlas— son neutralizados bajo etiquetas terapéuticas o inclusivas. El arte se vuelve un dispositivo profiláctico: limpia el presente para que el futuro siga siendo el mismo. Y, como sabemos, el futuro no será el mismo.

Cuando Amoedo posa sonriente junto a la policía cultural del orden simbólico, lo hace en nombre de la armonía social. Pero la armonía, en este contexto, es violencia ralentizada. Lo que parece estabilidad es en realidad la continuidad de un castigo que ya no necesita garrote ni celda, sólo programación cultural. En cambio, una canción como la de Martí o una novela como las de Pynchon desajustan el oído del poder. Obligan a pensar fuera de la métrica.

Si la canción dice “Toca castigar al mundo”, el arte institucional responde: “Lo hacemos por tu bien.” Esa es la dialéctica contemporánea. En el fondo, ambas frases comparten el mismo verbo —castigar— pero lo orientan en direcciones opuestas. Martí lo usa para revelar el absurdo de la culpa moderna; Amoedo, para administrarla como amenaza. Lo que está en juego no es sólo una diferencia estética, sino una disputa por el sentido del tiempo. En el museo, el tiempo está bajo control: las obras se restauran, los relatos se ordenan, las identidades se validan. En la canción o en la literatura disonante, el tiempo se rompe, se descompone, se abre. El poder teme esa apertura porque interrumpe su gramática: sin cronología, no hay castigo posible.

Romper el tiempo lineal es un gesto político antes que metafísico. Pynchon y Martí, cada uno en su medio, lo actualizan: escriben o cantan contra la cronología del poder. La pregunta, entonces, no es sólo dónde está el arte, sino cuánto tiempo puede resistir antes de ser absorbido. Mientras escribo esto en Dublín, pienso que la diferencia entre la caminata en Dún Laoghaire y las salas blancas de las fundaciones es precisamente esa: allá el tiempo se deja vivir; acá se lo gestiona. El poder no teme a la crítica, teme al desajuste. La línea recta es su medida. Por eso toda verdadera obra, hasta una canción pop, es una forma de desobediencia temporal.

La hija, la herencia y el mito de la sangre

En Vineland, Thomas Pynchon introduce una figura que resume el colapso de toda revolución: Prairie Wheeler, la hija de Zoyd Wheeler y Frenesi Gates, exguerrilleros que en los años setenta habían creído en la posibilidad de destruir el sistema. Prairie crece en los ochenta, en una California ya convertida en parque temático del consumo, donde las viejas consignas revolucionarias sobreviven en formato televisivo. No hay continuidad posible entre la militancia de los padres y la adolescencia de la hija: sólo hay herencia sin transmisión. Prairie es hija de una utopía derrotada y de una biología culpable. Pynchon la dibuja como testigo de una revolución que se volvió genética, como si la sangre misma hubiera absorbido la culpa y la esperanza.

En la película de Anderson, Prairie es hija de una utopía derrotada y de una biología culpable. Pynchon, en la novela, la dibuja como testigo de una revolución que se volvió genética, como si la sangre misma hubiera absorbido la culpa y la esperanza.

Tweet

En One Battle After Another, Anderson recoge ese motivo y lo traduce al cine: Willa Ferguson, la hija del personaje de DiCaprio y de una militante asesinada, hereda la lucha como si fuera una predisposición, una marca inscrita en el cuerpo. “Lo llevo en la sangre”, dice en una de las primeras escenas. Es una frase aparentemente inocente, pero en su centro late una intuición perturbadora: la revolución como herencia eugenésica. La causa se naturaliza, el compromiso se convierte en ADN. Ese desplazamiento del plano político al biológico no es accidental. Es la versión contemporánea del viejo sueño del poder: que la diferencia deje de ser ideológica para volverse genética, que el conflicto se traduzca en herencia. Si antes se castigaban las ideas, ahora se patologiza la identidad. Si antes la rebeldía era un acto, hoy se diagnostica como condición. La biología reemplaza al tiempo. Y cuando el tiempo deja de importar, la historia queda abolida.

Ahí es donde la figura de la hija adquiere peso simbólico. No sólo porque representa la continuidad familiar, sino porque encarna la imposibilidad de romper la cronología del poder. El sistema absorbe incluso la genealogía de la disidencia. La guerrillera muere, pero su hija repite su destino como si obedeciera a un código genético. La revolución se hereda, no se elige. La libertad se convierte en linaje. Esa idea —tan presente en la película y en Pynchon— reaparece en la cultura actual con formas distintas: la noción de talento heredado, de trauma familiar, de pureza identitaria. Todo lo que antes era conflicto político se reescribe hoy como predisposición. La rebeldía se hereda, el arte se hereda, la culpa se hereda. El resultado es perverso: la diferencia deja de tener historia. Se vuelve naturaleza.

El poder celebra ese cambio porque lo libera de su mayor amenaza: la contingencia. Si las cosas son “de sangre”, ya no hay tiempo que romper, ni historia que revisar. Todo queda fijado. El relato de la herencia sustituye al relato del devenir. Por eso el discurso eugenésico —aunque se disfrace de psicología o de biología cultural— sigue siendo una tecnología del tiempo. Su objetivo es impedir la ruptura, garantizar la repetición. En este punto, la conexión con el arte institucional es directa. Así como la hija repite la historia de los padres, el arte oficial repite las estructuras del poder que dice cuestionar. En lugar de interrumpir, hereda. En lugar de fracturar el tiempo, lo preserva. Los museos, las fundaciones, las residencias artísticas operan como máquinas de filiación: reproducen el linaje del prestigio, aseguran la continuidad de los mismos apellidos, los mismos nombres, las mismas narrativas. El sistema se hereda; no se discute.

Cuando Glissant habla de la necesidad de romper el tiempo lineal, se refiere a esto: a interrumpir la lógica de la descendencia. “El pensamiento de la relación”, escribe, “nace del derecho a opacar la herencia.” Es decir: a no ser transparente ante el poder, a no dejar que la historia se reduzca a genealogía. Martí, con su insistencia en el olvido y el reinicio, propone algo parecido: una ética sin linaje, una música sin herederos. En cambio, el discurso biopolítico que estructura tanto Vineland como la película de Anderson no ofrece salida. Las hijas —ya sea Prairie Wheeler o Willa Ferguson— son espejos del fracaso paterno. No representan la superación del pasado, sino su congelamiento. Y en esa repetición hay una crítica precisa: mientras la historia se mida por sangre, el tiempo seguirá siendo propiedad del poder. Lo inquietante es que incluso las narrativas progresistas han adoptado esa lógica. La genealogía reemplazó al análisis, la identidad al pensamiento. La cultura celebra el linaje de la disidencia como si fuera una marca de autenticidad, sin advertir que al hacerlo restaura el principio que quería destruir. En vez de interrumpir el tiempo, lo clausura.

En cambio, el discurso biopolítico que estructura tanto Vineland como la película de Anderson no ofrece salida. Las hijas —ya sea Prairie Wheeler o Willa Ferguson— son espejos del fracaso paterno. No representan la superación del pasado, sino su congelamiento.

Tweet

En mi propio trabajo, esa constatación me devuelve siempre a la misma pregunta: ¿cuándo una acción, un gesto o una obra logran escapar del mandato genético del sistema? ¿Cuándo la diferencia deja de ser una herencia para convertirse en acontecimiento? Ni Pynchon ni Martí dan una respuesta. Pero ambos, a su manera, crean un espacio donde la historia deja de ser sangre y vuelve a ser ritmo. Quizá por eso una de las escenas claves de la película que asocia el cubículo del piso corporativo con la morgue y el crematorio es liberadora. La verdadera genealogía al perder sentido y el verdadero padre (no quiero spoilear) al confesar ser lo opuesto al macho que el imperio dice ser, el arte se abre paso: no como herencia, sino como interrupción.

Dublín, el mar y la posibilidad de otra cronología

Vuelvo al principio. A la caminata de esa noche con JP, Agustina y Alec en Dún Laoghaire, después de la película. El aire tenía esa densidad húmeda que sólo existe junto al mar y en ciudades donde el tiempo parece haber aprendido a respirar sin prisa. Caminábamos en silencio, cada uno sosteniendo una versión de la misma pregunta: ¿qué significa seguir creyendo en algo cuando el tiempo ya no promete redención?

Vuelvo al principio. A la caminata de esa noche con JP, Agustina y Alec en Dún Laoghaire, después de la película. Caminábamos sosteniendo la misma pregunta: ¿qué significa seguir creyendo en algo cuando el tiempo ya no promete redención?

Tweet

El hijo, con su entusiasmo de estudiante que lee a los clásicos y quiere filmar, fue el primero en romper el silencio. Dijo que le había impresionado el final, que el personaje de la hija —sin padre, sin código, sin causa— parecía no tener destino y, sin embargo, que esa falta de destino era lo más esperanzador de todo. “Porque si nada está escrito, todo puede empezar otra vez”, dijo. En esa frase había más filosofía que en muchas bibliotecas.

Pensé en Glissant, que escribió desde islas donde el mar no separa sino que une, y entendí que lo que él llama poética de la relación es también esto: cuatro personas distintas, en silencio, compartiendo un mismo tiempo roto, sin necesidad de llenarlo con sentido. El arte —cuando todavía es arte— ocurre así: en la grieta donde las palabras no alcanzan pero tampoco se rinden. Martí lo sabe cuando repite “olvidándonos”; Pynchon lo intuye cuando hace del olvido una forma de resistencia. Y yo lo sentí esa noche, caminando con dos personas que me ofrecían hospitalidad sin discursos, sólo con presencia. Ese gesto, tan simple, fue una forma de arte: la ética de la compañía como suspensión del tiempo lineal del miedo.

Desde que estoy en Dublín, pienso mucho en el mar como figura del tiempo que no avanza pero se mueve. No hay progreso en el oleaje: hay ritmo. Eso mismo falta en la cultura contemporánea, donde todo se mide por la velocidad de la circulación, donde incluso la sensibilidad se cuantifica. El arte institucional, como la política, depende de ese flujo: necesita resultados, métricas, justificación. Pero la experiencia del arte —esa que Martí, Pynchon y Glissant preservan— pertenece a otra cronología, una donde la demora es conocimiento.

El arte —cuando todavía es arte— ocurre así: en la grieta donde las palabras no alcanzan pero tampoco se rinden. Martí lo sabe cuando repite “olvidándonos”; Pynchon lo intuye cuando hace del olvido una forma de resistencia

Tweet

Caminar hasta el cine y volver fue, en ese sentido, un acto político. No porque tuviera intención de serlo, sino porque interrumpió mi propio automatismo. Después de meses de tensiones, de procesos judiciales, de protocolos y papeles, me encontré en una escena sin urgencia. Y comprendí que la libertad empieza en esa suspensión: cuando el tiempo deja de obedecer al miedo. A veces el cuerpo entiende antes que la mente. Mientras caminábamos de regreso, sentí una liviandad que no recordaba. El hijo de JP iba un poco adelante, y me pareció ver en él esa mezcla de inteligencia y curiosidad que ya es rara: la de quien todavía confía en el futuro, no como promesa, sino como espacio por inventar. Pensé que esa es la verdadera herencia: no la sangre, no el linaje, sino la capacidad de imaginar sin cronología.

Glissant decía que cada relación humana auténtica produce una desviación en la historia, una especie de micro-sismo que altera la continuidad del mundo. Anoche sentí algo de eso. Un escritor exiliado, un padre irlandés, una madre argentina y su hijo caminando bajo la lluvia fina: nada heroico, nada programático, pero suficiente para que el tiempo se volviera, por un instante, otra cosa.

Tal vez de eso se trate finalmente la pregunta que atraviesa todo este texto. No “¿dónde está el arte?”, sino cuándo sucede. Y la respuesta —si existe— no está en los museos ni en los manifiestos, sino en momentos como ese: en la pausa, en la conversación que no busca ganarle al silencio, en el gesto que no acumula capital simbólico. El arte sucede cuando una forma de vida interrumpe el tiempo del poder, aunque sea por unos segundos.

A veces imagino que ese es el código que DiCaprio olvida en la película. No un número ni una palabra, sino un ritmo. Un compás que no encaja con el reloj del mundo. Por eso no lo recuerda cuando lo tiene que recordar para reactivar los mecanismos de la revolución: porque el sistema le enseñó a pensar en secuencias, no en pulsos.

Mientras escribo esto, escucho otra vez el disco de Martí. La canción suena como una oración descentrada: el tiempo del loop, el eco del error. Y pienso que esa es nuestra única manera de seguir pensando el arte hoy: no buscar su lugar, sino acompañar su deriva. No medirlo, sino escucharlo. Dublín, con su clima inestable y su calma obstinada, es el escenario ideal para ese aprendizaje. Aquí el tiempo no se impone: se negocia. Uno puede perder una hora sin culpa, dejarse llevar por la lluvia, entender que la interrupción no es falla sino forma.

Mientras escribo esto, escucho otra vez el disco de Martí. La canción suena como una oración descentrada: el tiempo del loop, el eco del error. Y pienso que esa es nuestra única manera de seguir pensando el arte hoy: no buscar su lugar, sino acompañar su deriva.

Tweet

Por eso, cuando esta crónica termine, no habrá cierre. Porque el arte —cuando todavía se atreve— no cierra nada: abre intervalos. Si algo aprendí de JP, de su hijo, de Pynchon, de Martí y de Glissant, es que el futuro empieza cuando dejamos de exigirle coherencia al tiempo. Quizá eso sea escribir hoy: aprender a vivir en el intervalo, entre una canción que se repite y una ola que nunca llega igual. El resto —los museos, los premios, las genealogías— pertenece al tiempo del castigo. Yo prefiero quedarme acá, en esta otra cronología. Con el mar frente a mí, la lluvia cayendo, y la certeza de que por un momento —sólo uno— el tiempo se rompió y el arte, sin decirlo, volvió a suceder.

Chronicles from Dún Laoghaire: Paul Thomas Anderson, Lucas Martí, Thomas Pynchon, and Inheritance as the Nemesis of Revolution

Yesterday, I didn’t write. I was invited by JP, Agustina’s husband, by Agustina herself, and by their son —a luminous, brilliant teenager, one of those who still believe that intelligence can be a space of freedom— to see One Battle After Another at the Odeon in Dún Laoghaire. Directed by Paul Thomas Anderson, who freely adapts elements from Thomas Pynchon’s Vineland, the film follows a group of former revolutionaries who must reunite sixteen years later when an old enemy resurfaces, forcing them to rescue the daughter of one of their comrades. Leonardo DiCaprio, Sean Penn, Teyana Taylor, Benicio del Toro, and Regina Hall lead the cast.

The four of us walked to the cinema. I didn’t write yesterday because I chose to accept that invitation. And in that choice, I later realized, there was a lesson about time: to let the day fold upon itself, to abandon its forced productivity. To exist without promising. In Buenos Aires or London, every movement is measured by a goal; in Dublin, one can walk toward a film as one walks toward a pause. Dún Laoghaire has that air of elegance that survived poverty only to invert it—a mixture of fin-de-siècle grace and seaside parking lot familiarity that feels close to home, though in Hastings the same familiarity moves in the opposite direction, like England itself. Halfway there, JP pointed to a brick building and said a famous musician had once lived there—“a guy who refused to finish his songs.” I told him that seemed like a political gesture. He laughed.

We entered the Odeon. The lobby was almost empty. We bought popcorn that none of us finished. JP’s son —whose mind drifts between Virgil and Godard— explained to me, with contagious enthusiasm, how One Battle After Another plays with the myth of revolution as infinite repetition, through the code DiCaprio forgets to recall when he makes the call that would reactivate the group and their protective network. In the film, forgetting as denial and the elasticity of time as dissent form the axis of the story. I listened and thought that this young man, perhaps unknowingly, had already articulated the heart of what Édouard Glissant theorized: that history is not linear but archipelagic, that each generation inherits forgetting as a way of beginning again.

The film left us in silence. We walked back along the coast, the four of us, with the sea to our left and the lights of the boats trembling like memories not yet ready to disappear. We spoke little. JP said the film reminded him of the revolts of the 1980s, “when people still believed it was possible to change the system.” His son replied that perhaps the problem wasn’t the system but the calendar: we keep measuring change with old clocks. I said nothing. I thought that brief exchange was worth more than any conversation about contemporary art I’d had in recent months. Then Agustina reflected that truth never lives in the present—at least not for certain people. Nulla veritas in nunc. What else is writing if not that: being present in a scene without intervening, recording the rhythm by which time falls out of order.

What Pynchon teaches us, filtered through Anderson’s film, is the productivity of a broken chronology. When we got home, I kept thinking about the character of the guerrilla’s daughter —played by Willa Ferguson— who repeats the genetic mandate of revolution: the possibility of a change that doesn’t break time but makes it tremble.

Tweet

What Pynchon teaches us, filtered through Anderson’s film, is the productivity of a broken chronology. When we got home, I kept thinking about the character of the guerrilla’s daughter —played by Willa Ferguson— who repeats the genetic mandate of revolution: the possibility of a change that doesn’t break time but makes it tremble. That inheritance is problematic—not for being revolutionary but for being potentially eugenic. In Kirchnerist Argentina we had a moral elite marked by the blood of the fallen and their descendants. Perhaps the future of art lies elsewhere: with those who understand that the present doesn’t need heroes or moral lineages founded by heroes, but interruptions of those heritages. Perhaps that is what Glissant meant: the history of the modern world imposed a linear, colonial chronology that turned time into an instrument of domination. Against that, he proposed a poetics of relation, where time fragments and becomes archipelagic—not progressive but entangled, repeated, and reinvented through memory and errancy.

The Loop and Memory: From Lucas Martí to Pynchon

There is a line in Lucas Martí’s song —the one that repeats like a prayer: “Olvidándonos, olvidándonos. Todos desearíamos empezar de nuevo, ser hombres de nuevo, ser hombres más nuevos” (“Forgetting ourselves, forgetting ourselves. We would all wish to start again, to be men again, to be newer men”)— that has haunted me since I first heard it. It is not just the echo of a collective guilt or a desire for purification; it is something deeper: the awareness that the time of art and the time of power no longer coincide. Martí is not seeking redemption. He is searching for a rhythm that steps outside chronology.

In his new album, Políticamente de izquierdas, aristocráticamente de derechas (Politically Left-Wing, Aristocratically Right-Wing), there is a tone that doesn’t belong to the usual irony of Argentine pop —a lucid exhaustion, a sense that the present has become a minefield of repetitions. “Toca castigar al mundo, lo dejamos para vos” (“It’s your turn to punish the world; we’ll leave it to you”), he sings, and the phrase works as a diagnosis of our age. Punishment has been privatized. Everyone administers their own. What in the twentieth century were collective utopias has turned into a psychology of self-destruction. Martí’s music —like Pynchon’s literature before it— does not describe that transformation; it embodies it: it repeats to erode, it sings to create fractures in time.

“Toca castigar al mundo, lo dejamos para vos” (“It’s your turn to punish the world; we’ll leave it to you”), Argentine singers song writer Luca’s Martí says, and the phrase works as a diagnosis of our age. Punishment has been privatized. Everyone administers their own.

Tweet

Thomas Pynchon —that invisible writer who, since the 1960s, turned paranoia into a literary method— understood before anyone else that modern power doesn’t only control bodies, it controls the flow of time. In novels like Gravity’s Rainbow or Vineland, the past does not disappear: it reconfigures itself as simulacrum, parody, or trauma that returns on another frequency. In Vineland (1990), the dream of the American 1970s revolution collides with the media machinery of the Reagan era. The surveillance of the 1980s replaces the ideal; memory becomes commodified; and the former militants discover themselves living inside the spectacle they once vowed to destroy. Pynchon turns this coexistence of times —utopia and its ruin— into his narrative substance. Vineland does not advance; it circulates. The characters orbit around a past that refuses to close. The result is a writing in loop, where every attempt at remembering becomes another form of forgetting. It is a world where the archive replaces experience, where revolution survives as image.

Pynchon turns this coexistence of times —utopia and its ruin— into his narrative substance. Vineland does not advance; it circulates. The characters orbit around a past that refuses to close. The result is a writing in loop, where every attempt at remembering becomes another form of forgetting.

Tweet

Lucas Martí, in his record, performs a similar operation from another register. Repetition here is not a postmodern gimmick but an act of resistance. In an era that demands constant novelty, to repeat is to refuse the mandate of productivity. His music —with its layers of loops and dissolving choruses— works as a memory that refuses to move forward. That is where its power lies: pop not as a superficial genre but as a temporal experiment. If Pynchon wrote Vineland to show how television and the culture of spectacle had turned rebellion into programming, Martí responds from the other side —from the exhaustion of that programming. He sings from the ruins. Where Pynchon diagnosed the colonization of time, Martí suffers it as an intimate experience. His songs don’t try to destroy order; they inhabit its fatigue.

That aestheticized exhaustion carries political weight. When Glissant speaks of breaking linear time, he is not calling for progress to stop but for it to be freed from the colonial domination of the clock. Martí, perhaps unknowingly, shares that intuition: his lyrics move within a temporality that doesn’t want to arrive anywhere. In fact, the verb that recurs most in the album is olvidar —to forget. And in his case, forgetting is not surrender; it is a way out of the regime of official memory —the one that classifies, archives, and punishes.

Listening to the album in Dublin, the connection with Pynchon felt inevitable. Vineland depicts an America that tried to erase its revolutionary past and ended up as a caricature of itself. Martí’s record could be the soundtrack of that process: cultural Argentina in recent years, where official art has merged with the police discourse of order, repeats the same structure. Punishment as government, amnesia as state policy, irony as refuge.

Listening to the album in Dublin, the connection with Pynchon felt inevitable. Vineland depicts an America that tried to erase its revolutionary past and ended up as a caricature of itself.

Tweet

What is interesting is that neither Pynchon nor Martí settles into denunciation. There is no moralism in their work —there is structure. Both propose an ethics of disalignment: to live in a present where times no longer line up, where the past offers no guidance and the future no promise. It is Glissant’s archipelagic condition translated into pop culture and twenty-first-century narrative. In that sense, the question is no longer “Where is art?” but When does a fracture occur in the chronology imposed by power? When do a song, a novel, or even a fleeting scene in the street manage to twist time and suspend obedience, if only for a second? Martí sings that suspension; Pynchon writes it; and in both, revolution appears not as an event but as an interruption.

What is interesting is that neither Pynchon nor Martí settles into denunciation. There is no moralism in their work —there is structure. Both propose an ethics of disalignment: to live in a present where times no longer line up, where the past offers no guidance and the future no promise.

Tweet

As I walked through Dún Laoghaire last night, I thought that perhaps this is the true aesthetic legacy of the twentieth century: the discovery that all forms of freedom depend on a small act of asynchrony. On stepping out of rhythm. On letting time become irregular. In that irregularity, Martí and Pynchon meet —the musician and the novelist, pop and paranoia— both obsessed with the same question: how to stay alive in an age that demands we move forward when the most urgent thing is to stop.

The Art of Punishment: Amoedo, Showgirls, and the Chronology of Power

If in Martí and Pynchon time fractures, in official Argentine art it becomes a rule. That is the central difference. What for them is interruption, for the art system is restoration. Its function is not to think time but to administer it. I saw it clearly when I wrote about Ama Amoedo and the police performance at the charity gala in support of the Churruca Hospital —the hospital of the Federal Police. What presented itself as philanthropy or curatorial gesture revealed itself as a machinery of order, as threat. In Argentine institutional art —that of foundations, sponsored museums, art-and-health programs, and the corporate culture of correctness— time never stops; it circulates in the service of punishment. The aesthetics of order replace the question of freedom.

In that staging, Amoedo appears as an almost theological figure: the one who cleanses the stain, who restores lost purity. Her mission is not to create but to sustain the continuity of a moral narrative. Her work and her philanthropic policy align perfectly with what Foucault called pastoral power: a form of power that does not need to repress but heals and protects while classifying. The museum, the foundation, the biennial operate as temples where time is ordered and deviations are diagnosed.

This operation —art as administration of bodies and emotions— is not new. But in today’s context, after decades of aesthetic neoliberalism, it has reached an almost surgical refinement: it no longer needs to censor dissent, it absorbs it, aestheticizes it, turns it into display. Everything becomes an educational program or an inclusive project. Pain becomes experience; violence becomes performance; and time, once again, folds back upon itself.

Everything becomes an educational program or an inclusive project. Pain becomes experience; violence becomes performance; and time, once again, folds back upon itself.

Tweet

That is why, when I wrote about The Last Show Girl and the figure of Pamela Anderson, what interested me was the radical contrast: that film —a monument to vulgarity and desire— does not fear excess. It is a form of temporal disobedience. What official art represses in the name of elegance or social justice, pop exhibits as truth. Anderson, in her latest incarnation as The Last Show Girl, embodies failure with dignity, not guilt. And there appears the same thread that connects her to Martí and to Pynchon: the ethics of disalignment.

Power needs linearity because its logic is causal: first the crime, then the punishment; first the trauma, then the cure. That is Argentine heiress philanthropist Amoedo’s narrative —and the State’s. What Glissant, Pynchon, or Martí interrupt is precisely that causality. In their universes, causes do not produce predictable effects; they produce resonances, returns, detours. Time is not a line but a delta.

In contemporary Argentine art, by contrast, the circular time of prestige prevails. Every gesture returns to its institutional origin. Radicality is standardized, critique is subsidized. The artists who truly unsettle —who expose the system’s wounds without anesthetic— are neutralized under therapeutic or inclusive labels. Art becomes a prophylactic device: it cleanses the present so that the future can remain the same. And, as we know, the future will not remain the same.

When Amoedo smiles beside the cultural police of symbolic order, she does so in the name of social harmony. But harmony, in this context, is violence slowed down. What looks like stability is in fact the continuity of punishment —no longer needing baton or cell, only cultural programming. A song like Martí’s or a novel by Pynchon, by contrast, detune the ear of power. They force thought outside the meter.

In contemporary Argentine art, by contrast, the circular time of prestige prevails. Every gesture returns to its institutional origin. Radicality is standardized, critique is subsidized. The artists who truly unsettle are neutralized under therapeutic labels. Art becomes a prophylactic device.

Tweet

If the song says “Toca castigar al mundo” —“It’s your turn to punish the world”— institutional art replies, “We do it for your own good.” That is the contemporary dialectic. At bottom, both share the same verb —to punish— but direct it in opposite ways. Martí uses it to reveal the absurdity of modern guilt; Amoedo uses it to administer that guilt as threat.

What is at stake is not merely an aesthetic difference but a dispute over the meaning of time. In the museum, time is under control: works are restored, narratives ordered, identities validated. In the song or in dissonant literature, time breaks, decomposes, opens. Power fears that opening because it interrupts its grammar: without chronology, punishment is impossible.

To break linear time is a political gesture before it is a metaphysical one. Pynchon and Martí, each in his medium, enact that gesture: they write or sing against the chronology of power. The question, then, is not only where art is, but how long it can resist before being absorbed. As I write this in Dublin, I think of the difference between that walk through Dún Laoghaire and the white rooms of the foundations: there, time is allowed to live; here, it is managed. Power does not fear criticism; it fears dissonance. The straight line is its measure. That is why every genuine work —even a pop song— is a form of temporal disobedience.

The Daughter, Inheritance, and the Myth of Blood

In Vineland, Thomas Pynchon introduces a figure that encapsulates the collapse of every revolution: Prairie Wheeler, daughter of Zoyd Wheeler and Frenesi Gates —former guerrillas who, in the 1970s, believed in the possibility of destroying the system. Prairie grows up in the 1980s, in a California already turned into a theme park of consumption, where old revolutionary slogans survive only as television décor. There is no possible continuity between her parents’ militancy and her own adolescence; there is only inheritance without transmission. Prairie is the child of a defeated utopia and a guilty biology. Pynchon sketches her as a witness to a revolution that has become genetic —as if blood itself had absorbed both guilt and hope.

In One Battle After Another, Anderson takes up that motif and translates it into cinema: Willa Ferguson, the daughter of DiCaprio’s character and a murdered militant, inherits the struggle as if it were a predisposition, a mark inscribed in the body. “It’s in my blood,” she says in one of the opening scenes. It sounds like an innocent line, but at its core lies a disturbing intuition: revolution as eugenic inheritance. The cause becomes naturalized; commitment turns into DNA. That shift from the political to the biological plane is no accident. It is the contemporary version of an old dream of power —that difference should cease to be ideological and become genetic, that conflict should translate into heredity. Where ideas were once punished, now identities are pathologized. What was once an act of rebellion has become a diagnosis. Biology replaces time. And when time no longer matters, history is abolished.

Where ideas were once punished, now identities are pathologized. What was once an act of rebellion has become a diagnosis. Biology replaces time. And when time no longer matters, history is abolished.

Tweet

This is where the figure of the daughter acquires symbolic weight. Not only because she represents familial continuity, but because she embodies the impossibility of breaking the chronology of power. The system absorbs even the genealogy of dissent. The guerrilla mother dies, but her daughter repeats her destiny as though obeying a genetic code. Revolution is inherited, not chosen. Freedom becomes lineage.

That idea —so present in both Pynchon’s novel and Anderson’s film— reappears throughout contemporary culture in different guises: the notion of inherited talent, of family trauma, of identitarian purity. What was once political conflict is now rewritten as predisposition. Rebellion is inherited, art is inherited, guilt is inherited. The result is perverse: difference loses its history and becomes nature.

Power celebrates this change because it frees it from its greatest threat: contingency. If things are “in the blood,” there is no time left to break, no history left to rewrite. Everything is fixed. The story of inheritance replaces the story of becoming. That is why the eugenic discourse —even when disguised as psychology or cultural biology— remains a technology of time. Its aim is to prevent rupture, to guarantee repetition.

At this point, the connection with institutional art becomes clear. Just as the daughter repeats the parents’ story, official art repeats the structures of the power it claims to question. Instead of interrupting, it inherits. Instead of fracturing time, it preserves it. Museums, foundations, and residencies operate as machines of filiation: they reproduce the lineage of prestige, ensuring the continuity of the same surnames, the same names, the same narratives. The system is inherited, not debated.

When Edouard Glissant speaks of breaking linear time, he refers precisely to this: interrupting the logic of descent. “The thought of relation,” he writes, “is born from the right to obscure inheritance.” In other words, from the right not to be transparent before power, not to let history be reduced to genealogy. Martí, with his insistence on forgetting and beginning again, proposes something similar: an ethics without lineage, a music without heirs. By contrast, the biopolitical discourse structuring both Vineland and Anderson’s film offers no escape. The daughters —whether Prairie Wheeler or Willa Ferguson— are mirrors of paternal failure. They do not represent the overcoming of the past but its freezing. And in that repetition lies a precise critique: as long as history is measured by blood, time will remain property of power.

The biopolitical discourse structuring both Vineland and Anderson’s film offers no escape. The daughters —whether Prairie Wheeler or Willa Ferguson— are mirrors of paternal failure. They do not represent the overcoming of the past but its freezing.

Tweet

What is unsettling is that even progressive narratives have adopted this logic. Genealogy has replaced analysis; identity has replaced thought. Culture celebrates the lineage of dissent as a badge of authenticity, without realizing that in doing so it restores the very principle it sought to destroy. Instead of interrupting time, it seals it.

In my own work, this realization always brings me back to the same question: when does an action, a gesture, or a work manage to escape the genetic mandate of the system? When does difference cease to be inheritance and become event? Neither Pynchon nor Martí provides an answer. But both, in their own ways, create a space where history ceases to be blood and becomes rhythm.

Perhaps that is why one of the film’s key scenes —which conflates the corporate-floor cubicle with the morgue and the crematorium— feels liberating. When genealogy loses meaning, and the true father (no spoilers) confesses to being the opposite of the macho ideal the empire demands, art makes its way through: not as inheritance, but as interruption.

Dublin, the Sea, and the Possibility of Another Chronology

I return to the beginning —to that walk with JP, Agustina, and Alec in Dún Laoghaire after the film. The air had that humid density that exists only by the sea and in cities where time seems to have learned how to breathe without haste. We walked in silence, each of us holding our own version of the same question: what does it mean to keep believing in something when time no longer promises redemption?

Alec, with the enthusiasm of a student who reads the classics and dreams of making films, was the first to break the silence. He said he was struck by the ending —that the daughter’s character, without father, without code, without cause, seemed to have no destiny and yet, somehow, that absence of destiny was the most hopeful thing of all. “Because if nothing is written, everything can begin again,” he said. There was more philosophy in that sentence than in many libraries.

I thought of Glissant, who wrote from islands where the sea does not divide but connects, and I understood that what he called the poetics of relation is also this: four people, different in everything, sharing the same fractured time without needing to fill it with meaning. Art —when it is still art— happens like that: in the fracture where words fall short but do not give up. Martí knows it when he repeats “olvidándonos”; Pynchon intuits it when he turns forgetting into a form of resistance. And I felt it that night, walking with two people who offered me hospitality without speeches, only through presence. That gesture, so simple, was itself a kind of art: the ethics of companionship as the suspension of the linear time of fear.

Since I arrived in Dublin, I have been thinking of the sea as a figure of time —time that doesn’t advance but moves. There is no progress in the waves; there is rhythm. That is precisely what is missing from contemporary culture, where everything is measured by the velocity of circulation, where even sensitivity is quantified. Institutional art, like politics, depends on that flow: it requires results, metrics, justification. But the experience of art —the one Martí, Pynchon, and Glissant preserve— belongs to another chronology, one where delay is a form of knowledge.

Walking to the cinema and back was, in that sense, a political act. Not because it intended to be, but because it interrupted my own automatism. After months of tension, of legal processes, of protocols and paperwork, I found myself inside a scene without urgency. And I understood that freedom begins in that suspension —when time stops obeying fear. Sometimes the body understands before the mind. As we walked back, I felt a lightness I hadn’t felt in months. JP’s son walked a few steps ahead, and I saw in him that rare combination of intelligence and curiosity —the kind found in those who still trust the future, not as a promise, but as a space to be invented. That, I thought, is the real inheritance: not blood, not lineage, but the capacity to imagine without chronology.

Glissant wrote that every authentic human relation produces a deviation in history, a kind of micro-seism that alters the world’s continuity. I felt something of that last night —an exiled writer, an Irish father, an Argentine mother, and their son walking under a fine rain: nothing heroic, nothing programmatic, yet enough to make time become, for an instant, something else.

Perhaps that is, finally, the question that runs through this whole text. Not “Where is art?” but when does it happen? And the answer —if there is one— is not in museums or manifestos but in moments like that: in the pause, in the conversation that doesn’t seek to conquer silence, in the gesture that accumulates no symbolic capital. Art happens when a way of living interrupts the time of power, even if only for a few seconds.

Sometimes I imagine that this is the code DiCaprio forgets in the film —not a number or a word, but a rhythm. A pulse that doesn’t fit the clock of the world. That is why he cannot remember it when he needs to reactivate the mechanisms of the revolution: the system has taught him to think in sequences, not in beats. And perhaps the daughter senses this when she decides not to insist. In her final silence —staring at the sea— lies a lesson that runs through this whole story: freedom is not inherited; it is improvised.

As I write this, I am listening again to Martí’s record. The song sounds like an uncentered prayer —the time of the loop, the echo of error. And I think that this might be the only way left to think about art today: not to seek its place, but to accompany its drift. Not to measure it, but to listen to it. Dublin, with its unstable weather and obstinate calm, is the ideal stage for that lesson. Here, time does not impose itself; it negotiates. You can lose an hour without guilt, let yourself be carried by the rain, understand that interruption is not failure but form.

That is why, when this chronicle ends, there will be no conclusion. Because art —when it still dares— does not close anything: it opens intervals. If I learned anything from JP, from his son, from Pynchon, Martí, and Glissant, it is that the future begins when we stop demanding coherence from time. Perhaps that is what writing means today: learning to live in the interval, between a song that repeats and a wave that never arrives the same way twice. The rest —the museums, the prizes, the genealogies— belongs to the time of punishment. I would rather stay here, in this other chronology —with the sea before me, the rain falling, and the quiet certainty that for one moment —only one— time broke, and art, without announcing itself, happened again.

Deja una respuesta