Scroll Down for the English Version

TODAY MONDAY AT 21 UK TIME AND 18 ARGENTINA TIME, THE NEW EPISODE OF MY VERY SPECIAL YOUTUBE SERIES OF ‘HOW NOT TO BECOME SUBHUMAN’. THIS EPISODE IS NOT ABOUT ME BUT ABOUT A FACEBOOK POST PUBLISHED BY THE INFAMOUS SUSSEX POLICE

Parabola Liberal

Salvatierra no es una novela sobre el arte: es una parábola sobre el libre mercado. Bajo su tono calmo y su melancolía familiar, Mairal elabora una ideología muy precisa: la Argentina como país condenado a producir belleza sin valor hasta que el Norte la certifique. El arte, en esta lógica, sólo adquiere legitimidad cuando deja de pertenecer. El padre —Salvatierra— encarna esa tensión. Su vida y su obra están narradas desde la marginalidad: “A los nueve años, Salvatierra tuvo un accidente mientras paseaba a caballo con sus primos… cayó y quedó enganchado del estribo… le rompieron el cráneo y la mandíbula, y le dislocaron la cadera.”

Salvatierra no es una novela sobre el arte: es una parábola sobre el libre mercado. Bajo su tono calmo y su melancolía familiar, Mairal elabora una ideología muy precisa: la Argentina como país condenado a producir belleza sin valor hasta que el Norte la certifique. El arte, en esta lógica, sólo adquiere legitimidad cuando deja de pertenecer.

Tweet

La violencia fundacional del accidente marca toda su existencia. No sólo sobrevive, sino que pierde la voz: “Después del accidente, Salvatierra no volvió a hablar. Podía oír pero no hablar… aunque lo torturaba la sed, no pronunciaba una sola palabra. Lo que sí logró fue dibujar lo que quería.” Esa mudez es la condición de posibilidad del arte. Mairal no permite que el padre pinte desde la razón, la ideología o la palabra, sino desde el trauma. El artista es, literalmente, un ser sin voz: curado por una vieja tuerta, legitimado por el accidente y, por lo tanto, inocente de toda pretensión intelectual. Sólo así puede pintar. Sólo así puede ser tolerado. El arte de Salvatierra es, desde el inicio, una excepción patológica.

Mairal no permite que el padre pinte desde la razón, la ideología o la palabra, sino desde el trauma. El artista es, literalmente, un ser sin voz. Sólo así puede pintar. Sólo así puede ser tolerado. El arte de Salvatierra es, desde el inicio, una excepción patológica.

Tweet

Su producción obsesiva —kilómetros de rollos continuos— aparece justificada como catarsis, nunca como proyecto. Interesante, en el Rojas pasó lo mismo. La pintura se vuelve terapia. El genio argentino, para Mairal, no nace del pensamiento sino del accidente. El único artista nacional posible es el que no habla ni teoriza: naturalista, virtuosista y laborioso. Para eso hay que tener dinero y tiempo. Más tarde, el narrador se enfrenta al mito que se construye sobre ese silencio: “Este mito que se está armando en torno a la figura de Salvatierra nace a raíz de su silencio… El hecho de que él no haya dado entrevistas, ni haya participado de la vida cultural, ni haya expuesto nunca, hace que los curadores y críticos puedan llenar ese silencio con las opiniones y teorías más diversas.”

Espadol Mairal: Sólo el Norte puede interpretar al Sur

Y los críticos, como en toda parábola colonial, lo traducen en categorías importadas: “Leí que un crítico lo calificaba como art brut, un arte ingenuo y autodidacta… Otro mencionó semejanzas con el emakimono, esos largos dibujos enrollados propios del arte chino y japonés… Otro hablaba de los luministas de Mallorca.” El texto finge distancia, pero el gesto es claro: sólo el afuera puede interpretar al adentro. El hijo no comprende la obra; la Fundación Röell, sí. El museo europeo no sólo compra la pintura: compra el silencio del padre, ese mutismo que lo vuelve universal.

La barbarie muda se convierte en exotismo. Y la voz del hijo —que sí puede hablar— no vale nada frente a la mirada institucional que traduce al artista local en lenguaje global. Por eso la llegada de los holandeses funciona como epifanía económica y teológica: “Después de recibir algunas propuestas insolventes de galerías nacionales… llegó de Holanda la propuesta de la Fundación Röell. A ellos les interesó la obra porque estaban formando una colección de arte latinoamericano.” (… brut).

La llegada de los holandeses funciona como epifanía económica y teológica: “Después de recibir algunas propuestas insolventes de galerías nacionales… llegó de Holanda la propuesta de la Fundación Röell. A ellos les interesó la obra porque estaban formando una colección de arte latinoamericano.” (… brut).

Tweet

Boris y Hanna, con su escáner monumental, encarnan el rito de purificación. El archivo sustituye la experiencia. El arte se convierte en dato exportable. Y, en el proceso, el padre es despojado de todo resto humano: su obra deja de ser memoria y pasa a ser mercancía certificada. Lo que Mairal llama “un archivo digital” es, en realidad, una traducción moral: de lo húmedo a lo seco, del barro al bit, del río al museo. Cuando Hanna, la restauradora, escanea los rollos, limpia también la culpa.

El narrador la observa fascinado y frustrado —“fantaseé un encuentro sexual furtivo… pero no pasó nada”—, como si comprendiera que ni él ni su país pueden consumar el deseo del Norte, que no quiere humedad ni flujos pos-SIDA, sino datos secos y distantes. El erotismo, como la política, se vuelve un trámite: ella no lo toca porque ya lo clasificó. Lo perturbador no es sólo esa asimetría de deseo, sino el modo en que Mairal la naturaliza. El extranjero no roba: cura. El argentino no crea: provee materia prima. Y el padre —ese cuerpo mudo, pintor terapéutico criado entre mujeres, hijo de un accidente ecuestre— es la metáfora perfecta de una nación que sólo produce valor cuando es domesticada por la mirada extranjera.

El argentino no crea: provee materia prima. Y el padre —ese cuerpo mudo, pintor terapéutico criado entre mujeres, hijo de un accidente ecuestre— es la metáfora perfecta de una nación que sólo produce valor cuando es domesticada por la mirada extranjera.

Tweet

El libro, así leído, no es una elegía: es una pedagogía neoliberal. Cada institución local es corrupta, cada intervención europea, legítima. El hijo, narrador y heredero, cumple la función del gestor cultural contemporáneo: convertir la experiencia íntima en circulación internacional. El arte, la herencia y el trauma se traducen a la única lengua aceptada: la del mercado. Mairal, con una elegancia engañosa, convierte el problema político argentino en un problema de exportación. La corrupción —esa “suma ridículamente baja” ofrecida por el municipio— no es el problema: es el pretexto. El problema, sugiere la novela, es que el país no sabe venderse. Y Salvatierra, en ese sentido, es su antídoto perfecto: una narrativa higiénica sobre cómo purificar la mugre nacional y entregarla, limpia, a Europa.

Mairal, con una elegancia engañosa, convierte el problema político argentino en un problema de exportación. La corrupción —esa “suma ridículamente baja” ofrecida por el municipio— no es el problema: es el pretexto. El problema, sugiere la novela, es que el país no sabe venderse. Y Salvatierra, en ese sentido, es su antídoto perfecto: una narrativa higiénica sobre cómo purificar la mugre nacional

Tweet

El tiempo lineal y la memoria exportable

El segundo tema de Salvatierra es el tiempo. No el tiempo de la experiencia —que en la novela aparece sofocado, detenido, anegado como el propio paisaje del litoral— sino el tiempo abstracto del progreso. Mairal construye su ficción sobre una concepción temporal típicamente moderna: lineal, acumulativa y extractivista. Esa temporalidad es la del capital, del archivo y del museo. Lo que está en juego en la historia del padre mudo y su tela interminable no es la memoria, sino su traducción a valor de cambio.

El segundo tema de Salvatierra es el tiempo. No el tiempo de la experiencia —que en la novela aparece sofocado, detenido, anegado como el propio paisaje del litoral— sino el tiempo abstracto del progreso: lineal, acumulativa y extractivista.

Tweet

El mandato genealógico del abuelo español condensa esa ideología del tiempo ascendente: “Yo empecé en la pobreza total y llegué hasta esto; ustedes empiezan aquí, vamos a ver hasta dónde llegan.” La vida se concibe como línea de producción: una carrera de herencia donde cada generación debe “llegar más lejos”. El padre queda exento de ese mandato por accidente —literalmente—: la caída del caballo lo libra del progreso, lo margina de la virilidad productiva y lo instala en una existencia lateral, femenina, improductiva. Ese accidente, que en otros autores podría leerse como origen de una sabiduría trágica, en Mairal funciona como explicación biológica: la pintura es un síntoma.

El arte de Salvatierra es posible porque no es un “hombre completo”. El golpe, la mudez y la crianza entre mujeres lo convierten en un “ser inocente”, casi clínico. En otras palabras, su creatividad es permitida sólo bajo condición de invalidez. Por eso el hijo y los críticos lo inscriben enseguida dentro de una genealogía del art brut o del autodidacta naïf, que no es lo mismo: “un arte realizado de modo absolutamente ingenuo y autodidacta, sin intención artística.” Se lo despoja de agencia para integrarlo al mercado global como mercancía exótica. Mairal deja que ese proceso ocurra sin conflicto: el arte deja de ser un lenguaje para convertirse en un archivo de historia mínima con forma de gran relato.

El arte de Salvatierra es posible porque no es un “hombre completo”. El golpe, la mudez y la crianza entre mujeres lo convierten en un “ser inocente”, casi clínico. En otras palabras, su creatividad es permitida sólo bajo condición de invalidez.

Tweet

Ese desplazamiento hacia el archivo, hacia el JPG, es la verdadera metáfora del tiempo moderno en la novela. Los holandeses que llegan a digitalizar la tela —“traían un enorme escáner del Museo Röell para digitalizar cuadros en su tamaño original”— representan la etapa final de la extracción: la conversión de la historia en dato, del cuerpo en imagen, del río en píxel. Mairal naturaliza esa operación como si fuera homenaje. Lo que para otros sería violencia simbólica —la conversión de la memoria familiar en archivo museístico extranjero— para él es la forma ideal de supervivencia: ser exportable.

Desde el abuelo inmigrante hasta los curadores holandeses, todos comparten la misma lógica de apropiación del tiempo: el pasado vale sólo si produce plusvalía en el presente, aunque sea cultural. Cuando el narrador dice: “tengo que acostumbrarme a que la obra de Salvatierra ya no es más nuestra”, no describe una pérdida, sino una aceptación: el tiempo, como la patria, pertenece a quien sabe capitalizarlo.

El contraste con el río es fundamental. El río, que fluye y arrastra, representa una temporalidad otra: circular, indeterminada, mestiza. Es el reverso de la línea ascendente del abuelo. Allí transcurre el contrabando, no como delito sino como circulación alternativa, una economía paralela que burla el tiempo oficial del Estado y de la moral. Pero Mairal no la celebra; la transforma en metáfora de la decadencia nacional. Para él, contrabandear no es desobedecer al orden, sino confirmar el atraso argentino frente al orden global.

El contraste con el río es fundamental: circular, indeterminado, mestizo. Es el reverso de la línea ascendente del abuelo. Pero Mairal no lo celebra; lo transforma en metáfora de la decadencia nacional. Para él, contrabandear no es desobedecer al orden, sino confirmar el atraso argentino frente al orden global, salvo que sea para hacer lo que el Norte pide.

Tweet

Cuando el hijo descubre los rastros de esa economía sumergida —la relación del padre con contrabandistas, el rollo robado, la venganza local—, no intenta comprenderla sino descartarla con un gesto de elegancia moral. La escena entera revela el límite ideológico de Mairal: el pasado puede ser materia de relato, pero nunca de implicación. La historia familiar es un paisaje a estudiar, no un trauma a atravesar.

El hijo funciona como un detective del linaje —un Sherlock Holmes de la memoria— que investiga su propio pasado como si fuera ajeno. El pasado se vuelve zona de extracción, un depósito de datos del que obtener pruebas o anécdotas, pero no vínculos. Mairal no soporta el tiempo de la deuda; sólo el tiempo de la eficiencia. En el universo de Salvatierra, el tiempo nacional —hecho de repeticiones, heridas, supervivencias— debe ser superado por el tiempo abstracto del capital cultural. El arte sólo adquiere sentido cuando deja de pertenecer a su territorio.

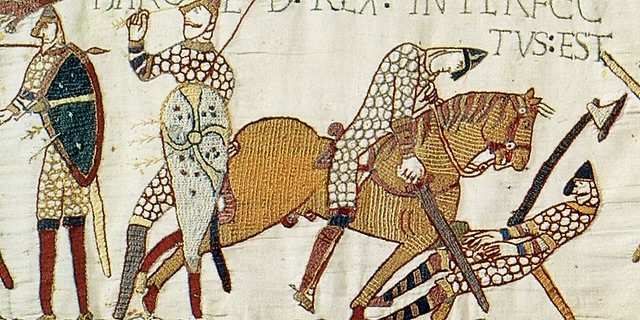

Bayeux: continuidad, rito y conquista

El Tapiz de Bayeux no es un tapiz técnico ni un “libro”: es un bordado narrativo de casi 70 metros, confeccionado sobre lino con hilos de lana, pensado para colgarse y recorrerse horizontalmente. Su temporalidad representada es secuencial, pero su régimen de recepción es ritual. En cada despliegue, la historia de Guillermo el Conquistador se reactualizaba: un pasado político convertido en presente ceremonial. Esa doble temporalidad —lineal y cíclica— hacía del bordado un arte del tiempo encarnado, donde la historia se tejía y se retejía con cada mirada.

En Salvatierra, esa tensión se aplana. El cruce del rollo hacia el Uruguay no reescribe una conquista, la administra. El hijo repite el gesto de Guillermo el Conquistador —cruzar el agua—, pero lo que antes fundaba soberanía ahora certifica valor. En Bayeux, el continuo bordado consagra una monarquía; en Mairal, la tela continua consagra un precio. La historia se convierte en logística: del galpón al bote, del bote a la frontera, de la frontera al museo. La continuidad, que en el bordado medieval era una forma de encarnar el tiempo, se convierte aquí en una forma de transportarlo.

El cruce del rollo hacia el Uruguay no reescribe una conquista, la administra. El hijo repite el gesto de Guillermo el Conquistador —cruzar el agua—, pero lo que antes fundaba soberanía ahora certifica valor. En Bayeux, el continuo bordado consagra una monarquía; en Mairal, la tela continua consagra un precio.

Tweet

El problema del art brut

En su sentido original, el término designaba producciones no institucionales cuya potencia residía en la fricción con los lenguajes legitimados. En Salvatierra, la etiqueta actúa al revés: lubrica la entrada del objeto en el sistema global del arte. La ingenuidad se convierte en certificado de autenticidad; la marginalidad, en plus de valor.

Pero la novela no explica cómo esa pintura “bruta” puede sostener racontos históricos. Si las telas son relatos de vida, necesariamente se organizan por hitos, emblemas, esquemas narrativos. Eso requiere composición, montaje y selección, es decir: todo lo contrario al automatismo. Mairal invoca la “brutalidad” como signo de pureza pero la llena de estructura. El resultado: una ficción higiénica de lo salvaje, un arte que se disfraza de inconsciente para mejor circular.

Mairal invoca la “brutalidad” como signo de pureza pero la llena de estructura. El resultado: una ficción higiénica de lo salvaje, un arte que se disfraza de inconsciente para mejor circular.

Tweet

Curaduría del trauma heredado

En esta transfiguración —de lo “bruto” a lo exportable— se juega el vínculo filial. El hijo hereda no sólo la obra del padre, sino la tarea de administrarla: clasificar, conservar, ofrecer. El gesto pictórico, que pudo haber sido un intento por fijar una identidad o reconciliarse con un tiempo propio, se vuelve objeto de gestión. La herencia se transforma en archivo, y el duelo en catálogo.

Mairal disfraza esa mutación bajo el signo de la continuidad amorosa —“cumplir el deseo del padre”—, pero en realidad es curaduría del trauma. El hijo no mira la tela para revivirla, sino para organizarla, reducirla a tramos y metros, medir su extensión, negociar su transferencia. Lo que podría haber sido una conversación con los muertos se convierte en proyecto museístico. El padre, pintando, actúa; el hijo, catalogando, administra. Donde uno intentaba salvar su vida por medio del trazo, el otro salva la obra para el mercado. El amor filial se confunde con el trabajo de exportación; la memoria, con la logística.

El padre, pintando, actúa; el hijo, catalogando, administra. Donde uno intentaba salvar su vida por medio del trazo, el otro salva la obra para el mercado. El amor filial se confunde con el trabajo de exportación; la memoria, con la logística.

Tweet

Ahí Mairal firma su manifiesto más elocuente: la Argentina no se salva trabajando, se salva trasladando. No se emancipa, exporta. El tapiz se vuelve aduana; la genealogía, logística; el hijo, agente de transporte. Y en esa transformación está toda la moral de Salvatierra: la del escritor argentino contemporáneo que ya no narra lo que somos, sino lo que podemos vender de nosotros.

Salvatierra by Pedro Mairal: Free Market as Emotion, Extractive Guilt as Family Redemption, and Unconditional Worship of the Global North” (ENG)

Salvatierra is not a novel about art: it is a parable about the free market. Beneath its calm tone and family melancholy, Mairal elaborates a very specific ideology: Argentina as a country condemned to produce beauty without value—until the North certifies it. In this logic, art acquires legitimacy only when it ceases to belong. The father—Salvatierra—embodies that tension. His life and work are narrated from the margins:

“At nine years old, Salvatierra had an accident while riding with his cousins… he fell and got caught in the stirrup… they broke his skull and jaw, and dislocated his hip.”

The founding violence of that accident marks his entire existence. He not only survives but loses his voice:

“After the accident, Salvatierra never spoke again. He could hear but not talk… although he was tormented by thirst, he did not utter a single word. What he managed to do was draw what he wanted.”

That muteness becomes the very condition of art. Mairal does not allow the father to paint from reason, ideology, or discourse, but from trauma. The artist is literally voiceless: cured by a one-eyed old woman, legitimized by the accident, and therefore innocent of any intellectual intention. Only thus can he paint. Only thus can he be tolerated. Art, from the outset, is a pathological exception.

His obsessive production—kilometres of continuous rolls—is justified as catharsis, never as project. Painting becomes therapy. For Mairal, the Argentine genius does not arise from thought but from accident. The only national artist imaginable is one who does not speak or theorize: naturalistic, virtuosic, and industrious. To achieve that, one must have time and money. Later, the narrator confronts the myth built upon that silence: “This myth growing around Salvatierra’s figure arises from his silence… The fact that he never gave interviews, never participated in cultural life, never exhibited, allows curators and critics to fill that silence with their own theories.”

And the critics, as in every colonial parable, translate him through imported categories:

“I read that one critic called him art brut, an ingenuous and self-taught art… Another mentioned similarities with the emakimono, those long scrolls of Chinese and Japanese art… Another compared him to the luminists of Mallorca.”

The text feigns distance, but the gesture is clear: only the outside can interpret the inside. The son does not understand the work; the Röell Foundation does. The European museum not only buys the painting—it buys the father’s silence, the muteness that makes him universal. Barbarism becomes exoticism. And the son’s voice—who can speak—has no value before the institutional gaze that translates the local artist into global language. Thus, the arrival of the Dutch curators functions as an economic and theological epiphany: “After some insolvent offers from national galleries, a proposal came from Holland—from the Röell Foundation. They were interested because they were assembling a collection of Latin American art.”

Boris and Hanna, with their monumental scanner, embody a ritual of purification. The archive replaces experience. Art becomes exportable data. In the process, the father is stripped of every human remainder: his work ceases to be memory and becomes certified merchandise. What Mairal calls “a digital archive” is in fact a moral translation: from mud to bit, from river to museum. When Hanna, the restorer, scans the rolls, she cleans the guilt along with the dirt.

The narrator observes her, fascinated and frustrated— “I fantasized about a furtive sexual encounter… but nothing happened.” —as if realizing that neither he nor his country can consummate the desire of the North, which no longer wants fluids, humidity or post-AIDS flesh, but dry data. Eroticism, like politics, becomes procedure: she does not touch him because she has already classified him. What is disturbing is not only this asymmetry of desire but the way Mairal naturalizes it. The foreigner does not steal—she heals. The Argentine does not create—he provides raw material. And the father—mute painter, raised by women, son of an equestrian accident—is the perfect metaphor for a nation that only produces value once domesticated by foreign gaze.

Read this way, the book is no elegy—it is a neoliberal pedagogy. Every local institution is corrupt; every European intervention, legitimate. The son, narrator and heir, assumes the role of the contemporary cultural manager: turning intimate experience into international circulation. Art, inheritance and trauma are translated into the only acceptable language: the language of the market. With deceptive elegance, Mairal converts Argentina’s political problem into one of export logistics. Corruption—the “ridiculously small sum” offered by the municipality—is not the problem; it is the pretext. The real problem, the novel suggests, is that the country does not know how to sell itself. And Salvatierra, in that sense, is its perfect antidote: a hygienic narrative on how to cleanse national filth and deliver it, pristine, to Europe.

Linear Time and Exportable Memory

The second theme of Salvatierra is time—not lived time, which in the novel appears suffocated and stagnant like the flooded landscape of the littoral, but abstract, progressive time. Mairal builds his fiction upon a typically modern conception of temporality: linear, accumulative, extractivist. It is the time of capital, archive, and museum. What is at stake in the story of the mute father and his endless canvas is not memory, but its conversion into exchange value.

The grandfather’s maxim condenses that ideology of upward time: “I started from nothing and got this far; you begin here, let’s see how far you get.” Life is conceived as a production line: each generation must go further. The father escapes that mandate through accident—literally. The fall from the horse frees him from progress, excludes him from productive virility, and situates him in a lateral, feminine, unproductive existence. That accident, which other writers might have turned into tragic wisdom, in Mairal becomes biological explanation: painting is a symptom.

Art, here, is possible only under conditions of disability. The blow, the muteness, and the upbringing among women make the father “innocent,” almost clinical. His creativity is permitted only as pathology. Hence, critics insert him within the genealogy of art brut or naïve autodidacts:

“an art made in an entirely naïve and self-taught way, without artistic intention.”

He is deprived of agency to be integrated into the global market as exotic commodity. Mairal allows this process to unfold without conflict: art ceases to be language and becomes an archival narrative, a continuous, exportable record of life. The shift toward the archive, toward the JPG, is the true metaphor of modern time in the novel. The Dutch team arriving to digitize the canvas— “They brought a huge scanner from the Röell Museum to digitize paintings in their original size”— represent the final stage of extraction: the conversion of history into data, of body into image, of river into pixel. Mairal naturalizes that operation as homage. What would be, for others, a symbolic violence—the transformation of family memory into a foreign museum’s archive—becomes, for him, the ideal mode of survival: exportability.

From the Spanish grandfather to the Dutch curators, everyone shares the same logic of temporal appropriation: the past is valuable only if it can yield cultural surplus value. When the narrator says, “I have to get used to the idea that Salvatierra’s work is no longer ours,” he is not describing loss, but acceptance: time, like the homeland, belongs to whoever can capitalize it.

The river provides the counterpoint. Flowing and cyclical, it represents an alternative temporality—circular, mestizo, resistant. There takes place the smuggling, not as crime but as parallel circulation, an economy of resistance that mocks the official time of the State. Yet Mairal refuses that ambivalence: for him, smuggling is not defiance but proof of national backwardness.

When the son uncovers traces of that submerged economy—the father’s ties to smugglers, the stolen roll, the local revenge—he discards them with moral elegance. The scene exposes the novel’s ideological limit: the past may be narrated, but never implicated. Family history is a landscape to study, not a trauma to inhabit. The narrator becomes a detective of lineage, a Sherlock Holmes of memory, investigating his own origin as if it belonged to someone else. The past turns into a zone of extraction—a deposit of anecdotes, never of bonds. Salvatierra cannot endure the time of debt; only the time of efficiency. National time—made of repetition, wounds, survivals—must be overcome by the abstract time of cultural capital. Art only makes sense once it no longer belongs.

In Salvatierra, the past does not return as ghost but as inventory. Mairal replaces the spectral unease of memory with the safety of the archive. Where memory should open a wound or summon a debt, the narrative imposes the hygienic distance of the observer. The son does not speak with the dead, only about them. He does not listen to the father’s silence; he translates it into data. The family story does not haunt him; it instructs him. That gesture embodies a modern moral evasion: to turn trauma into narrative in order to avoid contact. Memory does not hurt; it is studied. Mourning becomes description. The past, stripped of its power to disturb, becomes landscape—visible, narratable, harmless. A world where experience is preserved but not felt; where the archive replaces mourning, and observation replaces implication.

Bayeux: Continuity, Rite, and Conquest

The Bayeux Tapestry is not a tapestry in the technical sense, nor a “book.” It is a narrative embroidery nearly seventy meters long, worked on linen with wool threads, meant to be hung and read horizontally. Its represented temporality is linear, but its mode of display is ritual. Each unfolding of the embroidery reactivated the Norman conquest: a political past reenacted as ceremonial present. This double temporality—linear and cyclical—made Bayeux a medium where history became an embodied recurrence.

In Salvatierra, that tension is flattened. The crossing of the roll toward Uruguay does not reenact a conquest; it administers one. The son repeats William the Conqueror’s gesture—crossing water—but what once founded sovereignty now certifies value. In Bayeux, the continuous embroidery legitimizes power; in Mairal, the continuous canvas legitimizes transfer. History turns into logistics: from shed to boat, from boat to border, from border to museum. Continuity, which in the medieval embroidery embodied time, here merely transports it.

The Problem of Art Brut

In its original sense, art brut named non-institutional productions whose force resided in their friction with legitimized languages. In Salvatierra, the label functions in reverse: it lubricates the object’s entry into the global system. Naïveté becomes a certificate of authenticity; marginality, a bonus of value.

But the novel never explains how such “brutal” painting could sustain historical narratives. If the rolls recount a life, they must involve selection, montage, composition—everything opposed to automatism. Mairal invokes “brutality” as purity but fills it with structure. The result is a hygienic fiction of the wild: art that poses as unconscious to circulate more freely. The father’s work lacks the manic density of Adolf Wölfli or the geometric trance of Martín Ramírez; it has the illustrative clarity of narrative art. More than raw art, it is purified art—a storyboard of life turned into CV.

The brut label thus becomes a moral exemption: it allows market participation without the stain of ambition. By calling it brut, Mairal neutralizes gesture and recasts it as a clean aesthetic of authenticity—and, despite the French, as illiterate, coarse, brute. This acceptance consummates the modernist transfiguration of the mute marginal father into a compliant brut. Where Bayeux thickened history with thread and collective labor, Salvatierra thins it into surface for scanning. The first made visible the time of work; the second erases it to accelerate circulation. Hence, Salvatierra’s painting is neither ritual nor delirious—it is functional. It has the continuity of the tapestry but the intentionality of an architectural plan. It does not narrate a life outside language, but the illusion that such an outside might still exist.

That is Mairal’s most cynical operation: turning the utopia of free expression into an aesthetic of well-designed obedience.

The Curatorship of Inherited Trauma

In this transfiguration—from the “brutal” to the exportable—the filial bond is rewritten. The son inherits not only the father’s work but the duty to administer it: classify, conserve, offer. What might have been a desperate act to fix identity or reclaim lived time becomes an object of management. The inheritance turns into archive; mourning into catalogue.

Mairal disguises that mutation under the sign of filial love—“fulfilling the father’s wish”—but in reality, it is curatorship of trauma. The son does not look at the canvas to revive it but to organize it, to reduce it to meters, to measure, negotiate, and transfer. What could have been a conversation with the dead becomes a museum project.

The father, painting, acts; the son, cataloguing, administers. The first tries to save his life through the brushstroke; the second saves the work for the market. Filial love collapses into export labor; memory collapses into logistics.

At that point, Mairal signs his clearest manifesto: Argentina is not saved by work but by transfer. It does not emancipate—it exports. The tapestry becomes customs checkpoint; genealogy becomes logistics; the son becomes transport agent. And in that transformation resides the entire moral horizon of Salvatierra: the worldview of the contemporary Argentine writer who no longer narrates what we are, but what of ourselves can still be sold.

TODAY MONDAY AT 21 UK TIME AND 18 ARGENTINA TIME, THE NEW EPISODE OF MY VERY SPECIAL YOUTUBE SERIES OF ‘HOW NOT TO BECOME SUBHUMAN’. THIS EPISODE IS NOT ABOUT ME BUT ABOUT A FACEBOOK POST PUBLISHED BY THE INFAMOUS SUSSEX POLICE

Deja una respuesta