The English Version is Scrolling Down. ‘

El paisaje como archivo cultural de la memoria

Quienes están siguiendo conmigo el Curso de Arte de Paisajes, en particular el bloque sobre Paisaje, Tiempo y Memoria, saben que venimos trabajando el paisaje no como fondo natural sino como tecnología cultural, siguiendo a Simon Schama. Leer hoy Landscape and Memory mientras la Patagonia arde no es una coincidencia: es una comprobación. Los incendios desatendidos en Chubut, en el contexto del retiro deliberado del Estado y los recortes ambientales del gobierno de Javier Milei, muestran con brutal claridad que el paisaje sigue siendo tratado como superficie prescindible. El fuego no es solo una catástrofe climática: es una forma contemporánea de olvido. Y ese olvido no nace hoy, sino que se inscribe en una larga tradición nacional que convirtió a la Patagonia en desierto imaginado, refugio silencioso, pantalla estética y, finalmente, territorio sacrificable.

Leer hoy Landscape and Memory de Simon Schama, mientras la Patagonia arde no es una coincidencia: es una comprobación. Los incendios desatendidos en Chubut, en el contexto de los recortes del gobierno de Javier Milei, muestran con brutal claridad que el paisaje sigue siendo tratado como superficie prescindible. El fuego no es solo una catástrofe climática: es una forma contemporánea de olvido.

Tweet

El historiador Simon Schama plantea una pregunta fundamental: “¿Cuando miramos un paisaje, vemos naturaleza o cultura?” En su obra Landscape and Memory argumenta que todo paisaje –ya sea un bosque, un río o una montaña– es “una obra de la mente, un depósito de las memorias y obsesiones de las personas que lo contemplan” . Es decir, el paisaje funciona como una tecnología cultural: no es un espacio neutro, sino un escenario construido por nuestras narrativas históricas, mitos y recuerdos colectivos. De este modo, el entorno natural se convierte en un archivo de memoria, donde cada elemento del paisaje guarda capas de significado –desde símbolos sagrados hasta traumas históricos– inscritos por quienes lo habitan o conquistan.

Esta concepción del paisaje como superficie cultural nos permite entender cómo ciertas visiones del territorio pueden naturalizar el olvido o la violencia. Los paisajes se moldean con historias: se diseñan físicamente (a través de obras, fronteras, monumentos) y simbólicamente (a través de nombres, relatos y silencios). Schama demuestra, por ejemplo, cómo diferentes culturas proyectaron en sus entornos naturales sus valores e ideologías –desde el culto nazi al bosque “germánico” primigenio hasta la disputa simbólica en los relieves de Mount Rushmore . En resumen, el paisaje es una pantalla sobre la que se proyecta la memoria cultural: puede revelar vínculos profundos entre naturaleza y nación, pero también ocultar tras su belleza geográfica las historias de dominación y resistencia que allí ocurrieron.

El paisaje es una pantalla sobre la que se proyecta la memoria cultural: puede revelar vínculos profundos entre naturaleza y nación, pero también ocultar tras su belleza geográfica las historias de dominación y resistencia que allí ocurrieron.

Tweet

Patagonia en llamas: incendios, colapso ambiental y despojo contemporáneo

En los últimos años, los bosques andinos de Patagonia arden cada verano de forma devastadora, revelando nuevas dinámicas de violencia sobre el territorio. Los incendios forestales recientes en Chubut (2024-2026) son mucho más que desastres “naturales”: funcionan como síntoma político, económico y visual de un colapso ambiental entrelazado con la privatización del territorio. Ver cada temporada al cielo patagónico cubierto de humo y miles de hectáreas calcinadas se ha vuelto una imagen repetida, casi un macabro ritual de verano . En el arranque de 2026, por ejemplo, el fuego arrasó más de 6.000 hectáreas solo en Chubut y zonas vecinas, provocando evacuaciones masivas, muertes y destrucción de viviendas y bosques nativos en localidades como El Hoyo, Epuyén y Lago Puelo .

Los incendios forestales recientes en Chubut (2024-2026) son mucho más que desastres “naturales”: funcionan como síntoma político, económico y visual de un colapso ambiental entrelazado con la privatización del territorio.

Tweet

Estos incendios evidencian fallas estructurales y disputas por la tierra. Por un lado, las autoridades –tanto provinciales como nacionales– suelen apresurarse a buscar “culpables” en lugar de enfocarse en la prevención. En Chubut, el gobernador Ignacio Torres ha insinuado reiteradamente la teoría de “atentados coordinados” atribuidos a grupos mapuches radicalizados. Este discurso del “enemigo interno incendiario” no es nuevo: desde 2017 se viene usando la figura del “terrorismo mapuche” para explicar siniestros, pese a no existir una sola condena firme que demuestre que comunidades originarias provocaron incendios forestales de gran escala. Organizaciones de derechos humanos denuncian que esta narrativa opera más bien como “cortina de humo” para desviar la atención de los recortes presupuestarios y la desidia estatal en materia ambiental . De hecho, en 2025 el gobierno nacional redujo en un 78% el presupuesto del Servicio de Manejo del Fuego, dejando a los brigadistas sin recursos básicos . Así, mientras el Estado achica su presencia (menos aviones hidrantes, menos personal), llena ese vacío con un relato punitivo contra las comunidades locales.

Por otro lado, hay intereses económicos al acecho de la tierra que el fuego deja atrás. En Chubut venció en 2025 la ley provincial que prohibía vender tierras fiscales incendiadas por 10 años . Ahora, sin ese “cerrojo” legal, reaparece el fantasma de la especulación inmobiliaria: quemar montes tiene sentido para quienes buscan liberar áreas y luego adquirirlas baratas. Existe aún una ley nacional que impide cambiar el uso del suelo quemado por 30 a 60 años, pero el nuevo gobierno ultraliberal de Javier Milei ha amenazado con derogarla, tildando esas restricciones de “ataque a la propiedad privada” . No es casual que voceros de esa agenda hayan dicho cínicamente “que se prenda fuego todo, total luego vienen con el paquete de reformas”, anunciando su intención de flexibilizar las leyes de Tierras, Bosques, Manejo del Fuego y Glaciares . El fuego, entonces, no solo destruye bosques: abre paso a un negocio de tierra arrasada.

En Chubut venció en 2025 la ley provincial que prohibía vender tierras fiscales incendiadas por 10 años . Ahora, reaparece el fantasma de la especulación inmobiliaria. Existe aún una ley nacional que impide cambiar el uso del suelo quemado por 30 a 60 años, pero el nuevo gobierno ultraliberal de Javier Milei ha amenazado con derogarla,

Tweet

En este contexto, los incendios patagónicos se vuelven un símbolo visual del saqueo y la crisis climática. Las imágenes de bosques milenarios reducidos a cenizas y cielos anaranjados por el humo actúan como una alerta tangible del colapso ambiental en curso. Al mismo tiempo, reflejan la continuidad del modelo de despojo: ayer fueron las campañas militares y la colonización latifundista; hoy son el extractivismo, la desregulación y el cambio climático los que empujan a Patagonia al límite. Como señala un comunicado de comunidades Mapuche, “si hay fuego intencional, detrás hay un negocio inmobiliario” – es decir, intereses que ven en la destrucción una oportunidad . La combinación de vacío legal (terrenos sin protección) y discurso estigmatizante (culpar a indígenas) crea el escenario perfecto para una nueva ola de despojo territorial . En lugar de proteger a la población y el ambiente, las autoridades permiten que el paisaje patagónico vuelva a ser tratado como botín de unos pocos, esta vez bajo las llamas del capitalismo desregulado.

La combinación de vacío legal (terrenos sin protección) y discurso estigmatizante (culpar a indígenas) crea el escenario perfecto para una nueva ola de despojo territorial . En lugar de proteger a la población y el ambiente, las autoridades permiten que el paisaje patagónico vuelva a ser tratado como botín.

Tweet

Patagonia: territorio “vacío”, mito inhóspito y violencia fundacional

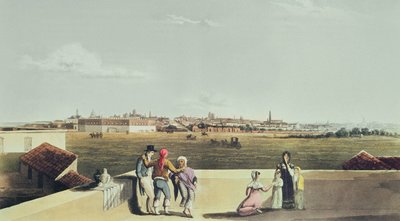

Pocos territorios ejemplifican mejor el paisaje como construcción ideológica que la Patagonia en Argentina y Chile. Históricamente, ambos Estados la concibieron como un desierto vacío, un confín inhóspito esperando la civilización. Ya en el siglo XIX se la trataba como terra nullius: “tierra de nadie” ocupada solo por “indios” sin soberanía reconocida . Bajo esa noción, las soberanías indígenas fueron ignoradas y brutalmente erradicadas, y tanto Chile como Argentina reclamaron Patagonia como propio sobre la base de nociones de ‘tierra de nadie’ para un sur que quisieron creer sin civilización, ni Estado, ni propiedad ni habitantes permanentes, vacío .

Ya en el siglo XIX se la trataba como terra nullius: “tierra de nadie” ocupada solo por “indios” sin soberanía reconocida y, por lo tanto, vendible.

Tweet

Esta narrativa del territorio vacío legitimó campañas militares de conquista y violencia estatal. En Argentina, la Campaña del Desierto liderada por Julio A. Roca (1878-1885) exterminó y desplazó a miles de indígenas tehuelches y mapuches, apropiándose de sus tierras al servicio del Estado central. Paradójicamente, al “despoblar violentamente” la región, Roca la volvió efectivamente más desértica –cumpliendo la profecía del vacío que él mismo promulgaba. Del lado chileno, la Pacificación de la Araucanía (1860s-1880s) y expediciones en Magallanes y Tierra del Fuego impusieron un esquema similar: ocupar mediante la fuerza militar y colonos europeos lo que describían como fronteras salvajes sin dueño. En ambos países, la Patagonia pasó a verse como reservorio de recursos más que hogar de pueblos: un botín para la nación moderna en expansión .

Apropiándose de sus tierras al servicio del Estado central, Roca la volvió más desértica –cumpliendo la profecía del vacío que él mismo promulgaba. Del lado chileno, la Pacificación de la Araucanía (1860s-1880s) y expediciones en Magallanes y Tierra del Fuego impusieron un esquema similar.

Tweet

Detrás del mito de la Patagonia inhóspita operaba así un poderoso imaginario estatal. Se promovía la imagen del “desierto” –una vasta estepa árida sin interés ni atractivo – para justificar su explotación. Esta representación simplificadora borraba las diferencias ecológicas y culturales de la región, permitiendo tratarla como una cantera utilitaria disponible para proyectos extractivos. Con el tiempo, ese imaginario perduró: Patagonia quedó consagrada como fuente de materias primas y energía, invisibilizando a sus habitantes originarios y minimizando el valor intrínseco de sus paisajes. La consecuencia política ha sido habilitar todo tipo de despojos –desde la entrega de grandes extensiones a terratenientes ovícolas europeos en el siglo XIX, hasta represas hidroeléctricas o megaproyectos mineros en el siglo XXI– bajo la idea de que, en tanto “vacío”, el sur puede usarse sin contemplaciones y también entregarse al sector privado.

Sin embargo, tras la postal de tierras aparentemente deshabitadas, subyace una violencia archivada en el paisaje. Los topónimos, museos locales y documentos históricos aún guardan rastros de aquel genocidio fundacional. Solo recientemente historiadores y comunidades han reivindicado la memoria indígena: se reconoce al fin que lo ocurrido con los Selk’nam en Tierra del Fuego fue un genocidio , y que la “Conquista del Desierto” argentina fue en realidad una guerra de exterminio. Irónicamente, la construcción del paisaje patagónico como “vacío” fue en sí una operación política para olvidar a sus víctimas: un paisaje reescrito para legitimar el despojo originario.

Solo recientemente historiadores y comunidades han reivindicado la memoria indígena: se reconoce al fin que lo ocurrido con los Selk’nam en Tierra del Fuego fue un genocidio , y que la “Conquista del Desierto” argentina fue en realidad una guerra de exterminio.

Tweet

‘Los Colonos’ en MUBI de Felipe Gálvez.

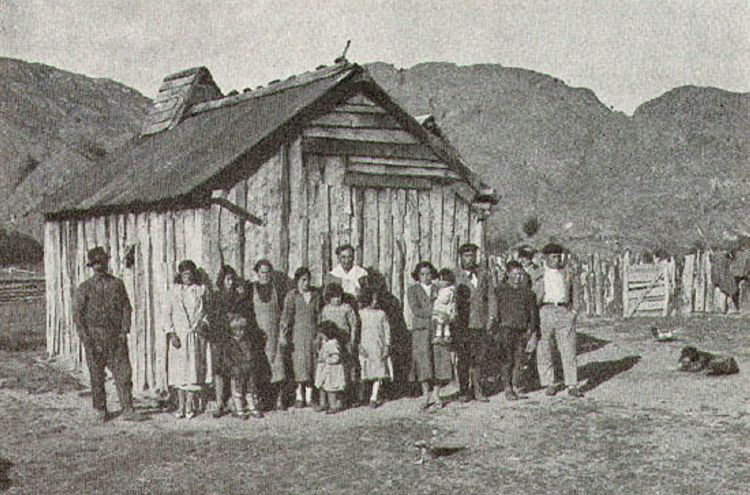

Frente a estos mecanismos de olvido y violencia, el arte y el cine emergen como herramientas de memoria crítica. Un ejemplo poderoso es la película chilena “Los Colonos” (título internacional: The Settlers), ópera prima del director Felipe Gálvez estrenada en 2023 . Disponible en la plataforma MUBI, este film recupera cinematográficamente la historia de la conquista de la Patagonia chilena, arrojando luz sobre uno de los capítulos más sangrientos y silenciados: el genocidio del pueblo Selk’nam a inicios del siglo XX. Gálvez plantea su obra como un western revisionista y visceral, que “expone la brutalidad del genocidio indígena en Patagonia” desmontando los mitos fundacionales del Estado chileno.

La película chilena “Los Colonos” (título internacional: The Settlers),de Felipe Gálvez estrenada en 2023. Ahora en MUBI, este film recupera la historia de la conquista de la Patagonia chilena, arrojando luz sobre uno de los capítulos más sangrientos y silenciados: el genocidio del pueblo Selk’nam a inicios del siglo XX.

Tweet

La trama de Los Colonos se sitúa en Tierra del Fuego, en 1901 . Allí, el magnate ganadero José Menéndez –figura histórica real, conocido como el “Rey de la Patagonia”– encarga a tres hombres una expedición para demarcar sus nuevas estancias ovinas. El grupo lo componen un teniente inglés (MacLennan), un mercenario estadounidense (Bill) y un joven mestizo chilote (Segundo). Pronto, lo que parecía una expedición administrativa se convierte en una violenta cacería humana: a sangre fría, los colonos comienzan a “limpiar” el territorio matando a los indígenas Selk’nam (onas) que encuentran a su paso . Segundo, el baqueano mestizo, se vuelve cómplice involuntario de la matanza, oscilando entre el horror y la obediencia. Siete años después, un funcionario enviado por el gobierno llega para “investigar” los crímenes, pero esa búsqueda de justicia tarda y tibia subraya la impunidad con que se construyeron las fronteras nacionales .

Los Colonos se sitúa en Tierra del Fuego, en 1901 . Allí, el magnate ganadero José Menéndez encarga a tres hombres una expedición para demarcar sus nuevas estancias ovinas. El grupo incluye un joven mestizo chilote. Pronto, una expedición administrativa se torna exterminio de indígenas Selk’nam (onas). El baqueano mestizo, se vuelve cómplice involuntario de la matanza, oscilando entre el horror y la obediencia… debida.

Tweet

Con una fotografía deslumbrante y cruda, Los Colonos aprovecha el contraste entre la belleza inhóspita del paisaje y la brutalidad de los hechos. Amplios planos generales muestran la inmensidad de la estepa y las montañas patagónicas en tonos fríos, empequeñeciendo a los personajes y resaltando la insignificancia moral de los conquistadores ante la naturaleza . En contrapunto, las escenas de violencia –tiroteos al amanecer entre la niebla, persecuciones a caballo, abusos– se filman de forma implacable y realista, sumergiendo al espectador en una experiencia profundamente perturbadora . El tono del film es deliberadamente incómodo, áspero, siguiendo la tradición del western crepuscular donde no hay héroes sino víctimas y victimarios atrapados en una misma espiral. La crítica la ha descrito como “un western crudo y violento sobre los pecados del colonialismo en Chile”. Gálvez, por su parte, señala que quiso generar una respuesta visceral, obligándonos a acompañar a los personajes y haciéndonos sentir casi cómplices, para así reflexionar sobre las violencias fundacionales que su país evitó contar .

Los Colonos narra, en suma, el nacimiento de las fronteras en el fin del mundo y cómo “los países escriben sus historias oficiales” ocultando masacres . Pone en el centro el genocidio Selk’nam –la matanza y aculturación forzada de un pueblo– y expone las alianzas entre Estado, capital extranjero (Menéndez era español) y racismos locales que orquestaron dicha limpieza étnica. El film ha sido aclamado internacionalmente (premio FIPRESCI en Cannes 2023 ) precisamente por atreverse a narrar esta verdad histórica con dureza poética. Su tono de denuncia es claro: no busca complacencia sino sacudir conciencias, enlazando aquel pasado con las reflexiones presentes sobre colonialismo, memoria y reparaciones pendientes. En palabras del director, “me interesaba mirar un momento menos conocido de la historia –un tiempo de mucha violencia– para que reflexionemos sobre el presente… Aproximo el genocidio Selk’nam desde la perspectiva de los colonizadores para pensar en cosas que, para mí, siguen ocurriendo hoy” . Así, Los Colonos funciona como contra-archivo visual: donde el paisaje fue antes mudo cómplice del olvido, el cine ahora lo convierte en testigo elocuente de la verdad.

Nazis en Bariloche: el paraíso alpino como refugio oscuro

Tras la Segunda Guerra Mundial, el idílico paisaje patagónico de Bariloche (Argentina) adquirió una nueva capa de significado siniestro. La región de lagos y montañas –promocionada turísticamente como “la Suiza argentina”– se convirtió en refugio de jerarcas nazis huidos de Europa. El gobierno de Juan Domingo Perón facilitó la entrada de miles de alemanes, a veces con identidades falsas. Varios de los más notorios criminales del Tercer Reich encontraron hogar en Bariloche: Josef Mengele vivió allí bajo el alias “José”, sacó registro de conducir local y hasta repartía tarjetas de médico con su nombre castellanizado ; Erich Priebke, ex capitán de las SS implicado en masacres en Italia, residió décadas como un vecino más hasta su captura en 1995 . La lista continúa con oficiales como Reinhard Kops, Adolf Eichmann, Hans Rudel, entre otros, que se “convirtieron en vecinos de los que nadie conserva un reproche” . En la vida cotidiana de Bariloche, su pasado infame corría como un río subterráneo, silenciado por una comunidad que prefería la amnesia.

Varios de los más notorios criminales del Tercer Reich encontraron hogar en Bariloche: Josef Mengele; Erich Priebke, ex capitán de las SS implicado en masacres en Italia, residió décadas como un vecino más hasta su captura en 1995. Reinhard Kops, Adolf Eichmann, Hans Rudel, entre otros. Todos, en Bariloche, lo sabían y lo silenciaban, prefiriendo la amnesia.

Tweet

El arribo de estos nazis reorganizó simbólicamente el paisaje barilochense. Por un lado, reforzó la impronta centroeuropea en la arquitectura y cultura local: chalets de estilo bávaro, clubes alpinos, chocolaterías y escuelas alemanas prosperaron –varias fundadas o apoyadas por inmigrantes germanos–, dotando a la ciudad de una “estética sólida y cuidada” al estilo centroeuropeo . Instituciones emblemáticas, como el prestigioso Colegio Alemán Primo Capraro, el Club Andino Bariloche o la orquesta local de música clásica, tienen deudas históricas con esa inmigración alemana . Se consolidó así la imagen de Bariloche como enclave “civilizado” y próspero en la Patagonia, un paraíso alpino transplantado al fin del mundo.

El arribo de estos nazis reorganizó simbólicamente el paisaje barilochense. Por un lado, reforzó la impronta centroeuropea en la arquitectura y cultura local: chalets de estilo bávaro, clubes alpinos, chocolaterías y escuelas alemanas. La Patagonia “civilizada” que tanto le gusta al Pro.

Tweet

Por otro lado, esa misma belleza escénica sirvió de pantalla para naturalizar el olvido. La postal de lagos azules y cumbres nevadas ocultaba una realidad incómoda: “un aura de destino paradisíaco que envuelve otra más oscura: la de un refugio perfecto, discreto, para fascistas” prófugos . Durante décadas, la complicidad y el silencio local permitieron que estos hombres –antiguas encarnaciones del horror nazi– se integraran sin rendir cuentas. El paisaje operó como coartada: en un entorno tan remoto y pintoresco, su presencia pasaba inadvertida o se relativizaba. Solo cuando la justicia internacional tocó la puerta (como en el caso Priebke) se rompió esa apariencia bucólica para exponer la verdad. Hoy, Bariloche capitaliza turísticamente esta historia oculta mediante recorridos y “tours nazis” para curiosos , pero el hecho de que tales visitas existan confirma cómo el paisaje patagónico puede archivar violencia: bajo el encanto natural permanecen latentes las memorias de complicidad y dolor, esperando ser narradas.

La pantalla patagónica como modelo de la amnesia argentina

A través de estos casos –la invención del desierto patagónico, la convivencia silenciosa con nazis, la tragedia de los incendios, y su recreación en el cine– se revela un hilo conductor: el paisaje patagónico opera como escenario de disputas por la memoria. Sus montañas, lagos y estepas han sido utilizados como pantalla para naturalizar el despojo, proyectando mitos de vacío o paraíso que encubren la violencia latente. Pero al mismo tiempo, ese paisaje carga con las huellas indelebles de lo ocurrido: es un archivo viviente donde la memoria soterrada puede aflorar en cualquier momento –sea en forma de un tour histórico, de un bosque calcinado que nos interpela, o de una película que reimagina el pasado.

La invención del desierto patagónico, la convivencia silenciosa con nazis, la tragedia de los incendios, y su recreación en el cine– se revela un hilo conductor: el paisaje patagónico opera como escenario de disputas por la memoria. Su “belleza” y “tragedia” ha sido utilizada como pantalla para naturalizar el despojo, proyectando mitos de vacío o paraíso que encubren la violencia latente.

Tweet

Hoy más que nunca, frente a un modelo que insiste en repetir el ciclo de saqueo y olvido, la Patagonia exige ser leída críticamente. Sus imágenes (idílicas o desoladoras) ya no pueden verse inocentemente; sus incendios claman por justicia ecológica y territorial; su historia pide ser reescrita incorporando las voces de los vencidos; y sus representaciones artísticas nos invitan a recordar donde otros quisieran hacer olvidar. Como decía Schama, el paisaje es un trabajo de la mente y de la memoria –y en el caso patagónico, esa mente colectiva está despertando. Reconocer las violencias archivadas tras la belleza natural es el primer paso para dejar de romanticizar el desierto y empezar a sanar el territorio con verdad y dignidad. Solo así la superficie del olvido puede transformarse en un lienzo de memoria y resistencia, donde el paisaje deje de encubrir el despojo y pase a reflejar, por fin, la justicia y la diversidad de su gente.

Patagonia in Flames: Milei as Nero Is Not an Exception but a Continuity in Argentine History’

Those who have been following my Course on Landscape Art, particularly the section devoted to Landscape, Time, and Memory, know that we have been approaching landscape not as a natural backdrop but as a cultural technology, following the work of Simon Schama. Reading Landscape and Memory today, while Patagonia is burning, is not a coincidence: it is a confirmation. The unattended wildfires in Chubut, in the context of the deliberate withdrawal of the state and the environmental budget cuts implemented by the government of Javier Milei, show with brutal clarity that landscape continues to be treated as a disposable surface. Fire is not only a climatic catastrophe: it is a contemporary form of forgetting. And this forgetting did not begin today; it is inscribed in a long national tradition that turned Patagonia into an imagined desert, a silent refuge, an aesthetic screen, and ultimately a sacrificial territory.

Reading Landscape and Memory today, while Patagonia is burning, is not a coincidence: it is a confirmation. The unattended wildfires in Chubut, in the context of the deliberate withdrawal of the state and the environmental budget cuts implemented by the government of Javier Milei, show with brutal clarity that landscape continues to be treated as a disposable surface.

Tweet

The historian Simon Schama poses a fundamental question: “When we look at a landscape, do we see nature or culture?” In Landscape and Memory, he argues that every landscape—whether forest, river, or mountain—is “a work of the mind, a repository of the memories and obsessions of the people who gaze upon it.” In other words, landscape functions as a cultural technology: it is not a neutral space, but a stage constructed through historical narratives, myths, and collective memories. In this way, the natural environment becomes an archive of memory, in which each element of the landscape contains layers of meaning—from sacred symbols to historical traumas—inscribed by those who inhabit or conquer it.

This understanding of landscape as a cultural surface allows us to grasp how certain territorial visions can naturalize forgetting or violence. Landscapes are shaped by stories: they are designed physically (through infrastructure, borders, monuments) and symbolically (through names, narratives, and silences). Schama shows, for example, how different cultures have projected their values and ideologies onto their natural environments—from the Nazi cult of the “primordial Germanic” forest to the symbolic struggle carved into the reliefs of Mount Rushmore. In short, landscape is a screen onto which cultural memory is projected: it can reveal deep connections between nature and nation, but it can also conceal, beneath geographic beauty, histories of domination and resistance that took place there.

Schama shows landscape as a screen onto which cultural memory is projected: it can reveal deep connections between nature and nation, but it can also conceal, beneath geographic beauty, histories of domination and resistance that took place there.

Tweet

Patagonia in Flames: Wildfires, Environmental Collapse, and Contemporary Dispossession

In recent years, Patagonia’s Andean forests have burned devastatingly every summer, revealing new forms of violence enacted upon the territory. The recent wildfires in Chubut (2024–2026) are far more than “natural” disasters: they function as political, economic, and visual symptoms of an environmental collapse intertwined with the privatization of land. Each season, the sight of smoke-filled skies and thousands of scorched hectares has become a recurring image—almost a macabre summer ritual. At the beginning of 2026 alone, fires consumed more than 6,000 hectares in Chubut and neighboring areas, triggering mass evacuations, deaths, and the destruction of homes and native forests in towns such as El Hoyo, Epuyén, and Lago Puelo.

These fires expose structural failures and land disputes. On the one hand, authorities—both provincial and national—tend to rush in search of “culprits” instead of focusing on prevention. In Chubut, Governor Ignacio Torres has repeatedly suggested the theory of “coordinated attacks” attributed to radicalized Mapuche groups. This discourse of the “incendiary internal enemy” is not new: since 2017, the figure of “Mapuche terrorism” has been used to explain forest fires, despite the fact that there is not a single firm conviction proving that Indigenous communities caused large-scale wildfires. Human rights organizations have denounced this narrative as a “smokescreen” designed to divert attention from budget cuts and state neglect in environmental policy. In fact, in 2025 the national government reduced the Fire Management Service budget by 78%, leaving firefighting brigades without basic resources. Thus, as the state shrinks its presence (fewer aircraft, fewer personnel), it fills that vacuum with a punitive narrative directed against local communities.

On the other hand, economic interests lurk behind the land left by the fire. In Chubut, a provincial law that prohibited the sale of burned public land for ten years expired in 2025. Without that legal safeguard, the specter of real-estate speculation reappears: burning forests makes sense for those seeking to clear areas and later acquire them cheaply. Although a national law still prohibits changes in land use on burned land for 30 to 60 years, Javier Milei’s new ultraliberal government has threatened to repeal it, labeling such restrictions an “attack on private property.” It is no coincidence that spokespeople from this agenda have cynically remarked, “Let everything burn—reforms will come afterward,” announcing their intention to loosen Land, Forest, Fire Management, and Glacier protection laws. Fire, then, does not merely destroy forests: it opens the door to a scorched-earth business model.

The current burning of Patagonia’s forests makes sense for those seeking to clear areas and acquire them cheaply. Although a national law still prohibits changes in land use on burned land for 30 to 60 years, Javier Milei’s new ultraliberal government has threatened to repeal it, labelling such restrictions an “attack on private property.”

Tweet

In this context, Patagonian fires become a visual symbol of plunder and climate crisis. Images of ancient forests reduced to ashes and skies turned orange by smoke act as tangible warnings of ongoing environmental collapse. At the same time, they reflect the continuity of dispossession: yesterday it was military campaigns and latifundist colonization; today it is extractivism, deregulation, and climate change pushing Patagonia to its limits. As one Mapuche community statement puts it, “If there is intentional fire, there is a real-estate business behind it”—that is, interests that see destruction as opportunity. The combination of legal vacuums (unprotected land) and stigmatizing discourse (blaming Indigenous peoples) creates the perfect conditions for a new wave of territorial dispossession. Instead of protecting people and the environment, authorities allow the Patagonian landscape to be treated once again as loot for the few—this time under the flames of deregulated capitalism.

Patagonia: “Empty” Territory, Inhospitable Myth, and Foundational Violence

Few territories better exemplify landscape as ideological construction than Patagonia in Argentina and Chile. Historically, both states conceived it as an empty desert, an inhospitable frontier awaiting civilization. As early as the nineteenth century, it was treated as terra nullius: “no one’s land,” inhabited only by “Indians” without recognized sovereignty. Under this notion, Indigenous sovereignties were ignored and brutally eradicated, and both Chile and Argentina claimed Patagonia as their own based on the idea of a southern land they chose to believe was without civilization, statehood, property, or permanent inhabitants—empty.

Few territories better exemplify landscape as ideological construction than Patagonia in Argentina and Chile. Historically, both states conceived it as an empty desert awaiting civilization. As early as the XIX century, it was treated as “no one’s land,” inhabited only by “Indians” without recognised sovereignty. Under this notion, anyone could take it.

Tweet

This narrative legitimized military conquest and state violence. In Argentina, the Conquest of the Desert led by Julio A. Roca (1878–1885) exterminated and displaced thousands of Tehuelche and Mapuche people, appropriating their lands for the central state. Paradoxically, by violently “depopulating” the region, Roca made it effectively more desert-like—fulfilling the prophecy of emptiness he himself proclaimed. On the Chilean side, the Pacification of Araucanía (1860s–1880s) and expeditions into Magallanes and Tierra del Fuego followed a similar logic: military force and European settlers occupied what were described as wild, ownerless frontiers. In both countries, Patagonia came to be seen as a reservoir of resources rather than a homeland—booty for the expanding modern nation.

Behind the myth of inhospitable Patagonia thus operated a powerful state imaginary. The image of the “desert”—a vast, arid steppe devoid of interest or attraction—was promoted to justify exploitation. This simplifying representation erased the region’s ecological and cultural diversity, enabling it to be treated as a utilitarian quarry for extractive projects. Over time, this imaginary persisted: Patagonia became consecrated as a source of raw materials and energy, rendering its original inhabitants invisible and minimizing the intrinsic value of its landscapes. The political consequence has been the authorization of every form of dispossession—from the transfer of vast tracts to European sheep barons in the nineteenth century to hydroelectric dams and megamining projects in the twenty-first—under the assumption that, as an “empty” land, the South could be used without restraint and handed over to private interests.

The image of the “desert”—a vast, arid steppe devoid of interest or attraction—was promoted to justify exploitation. This simplifying representation erased the region’s ecological and cultural diversity, enabling it to be treated as a utilitarian quarry for extractive projects.

Tweet

Yet beneath the postcard of seemingly uninhabited lands lies violence archived in the landscape. Place names, local museums, and historical documents still bear traces of that foundational genocide. Only recently have historians and communities reclaimed Indigenous memory: the atrocities committed against the Selk’nam in Tierra del Fuego are now recognized as genocide, and Argentina’s “Conquest of the Desert” is acknowledged as a war of extermination. Ironically, constructing Patagonia as “empty” was itself a political operation of forgetting—a rewritten landscape designed to legitimize original dispossession.

Los Colonos

on MUBI, by Felipe Gálvez

In the face of these mechanisms of forgetting and violence, art and cinema emerge as tools of critical memory. A powerful example is the Chilean film Los Colonos (The Settlers), the debut feature by director Felipe Gálvez, released in 2023. Available on MUBI, the film revisits the conquest of Chilean Patagonia, shedding light on one of the bloodiest and most silenced chapters in the region’s history: the genocide of the Selk’nam people in the early twentieth century. Gálvez frames his work as a visceral revisionist western that “exposes the brutality of Indigenous genocide in Patagonia,” dismantling the founding myths of the Chilean state.

The Chilean film Los Colonos (The Settlers) directed by Felipe Gálvez, released in 2023 and on MUBI, revisits the conquest of Chilean Patagonia, shedding light on one of the bloodiest and most silenced chapters in the region’s history: the genocide of the Selk’nam people in the early twentieth century.

Tweet

Set in Tierra del Fuego in 1901, the film follows a land baron, José Menéndez—historically known as the “King of Patagonia”—who commissions three men to mark out his new sheep ranches: an English lieutenant (MacLennan), an American mercenary (Bill), and a young Chilote mestizo (Segundo). What begins as an administrative expedition soon becomes a violent human hunt: the settlers coldly “clean” the land by killing Selk’nam (Ona) people they encounter. Segundo becomes an unwilling accomplice, torn between horror and obedience. Seven years later, a government envoy arrives to “investigate” the crimes, but the delayed, tepid search for justice underscores the impunity with which national borders were built.

Set in Tierra del Fuego in 1901, the film follows a land baron, José Menéndez who commissions three men to mark out his new sheep ranches. What begins as an administrative expedition soon becomes a violent human hunt: the settlers coldly exterminate the Selk’nam (Ona) people.

Tweet

With stunning yet harsh cinematography, Los Colonos exploits the contrast between the inhospitable beauty of the landscape and the brutality of events. Wide shots of the Patagonian steppe and mountains, rendered in cold tones, diminish the characters and highlight the moral insignificance of the conquerors before nature. Violent scenes—dawn shootouts in the mist, horseback chases, abuses—are filmed with relentless realism, plunging the viewer into a deeply disturbing experience. The film’s tone is deliberately abrasive, following the tradition of the twilight western, where there are no heroes, only victims and perpetrators trapped in the same spiral. Critics have described it as “a raw and violent western about the sins of colonialism in Chile.” Gálvez himself has said he wanted to provoke a visceral response, forcing viewers to accompany the characters and feel almost complicit, in order to reflect on foundational violences his country avoided confronting.

In sum, Los Colonos narrates the birth of borders at the end of the world and how “countries write their official histories” by concealing massacres. It places the Selk’nam genocide at the center and exposes the alliances between state power, foreign capital (Menéndez was Spanish), and local racism that orchestrated this ethnic cleansing. The film’s international acclaim—including the FIPRESCI Prize at Cannes 2023—stems precisely from its refusal to soften historical truth. Its denunciatory tone links past colonial violence with present debates on memory, reparations, and power. As Gálvez notes, “I was interested in looking at a lesser-known moment of history—a time of extreme violence—to reflect on the present… I approach the Selk’nam genocide from the colonizers’ perspective to think about things that, for me, are still happening today.” Los Colonos thus functions as a visual counter-archive: where the landscape once silently colluded with forgetting, cinema now turns it into an eloquent witness to truth.

In sum, Los Colonos narrates the birth of borders at the end of the world and how “countries write their official histories” by concealing massacres. It places the Selk’nam genocide at the center and exposes the alliances between state power, foreign capital (Menéndez was Spanish), and local racism that orchestrated this ethnic cleansing.

Tweet

Nazis in Bariloche: The Alpine Paradise as Dark Refuge

After World War II, the idyllic Patagonian landscape of Bariloche, Argentina, acquired a sinister new layer of meaning. The region of lakes and mountains—marketed as the “Argentine Switzerland”—became a refuge for Nazi officials fleeing Europe. Juan Domingo Perón’s government facilitated the arrival of thousands of Germans, sometimes under false identities. Several of the Third Reich’s most notorious criminals found shelter in Bariloche: Josef Mengele lived there under the alias “José,” obtained a local driver’s license, and even distributed business cards under his Hispanicized name; Erich Priebke, a former SS captain implicated in massacres in Italy, lived for decades as an ordinary neighbor until his arrest in 1995. The list continues with figures such as Reinhard Kops, Adolf Eichmann, and Hans Rudel, who “became neighbors whom no one reproached.” In everyday Bariloche life, their infamous past flowed like an underground river, silenced by a community that preferred amnesia.

Several of the Third Reich’s most notorious criminals found shelter in Bariloche: Josef Mengele; Erich Priebke, Reinhard Kops, Adolf Eichmann, and Hans Rudel, “became neighbors whom no one reproached.” Their infamous past flowed like an underground river, silenced by a community that preferred amnesia.

Tweet

Their arrival reshaped Bariloche’s symbolic landscape. On one hand, it reinforced a Central European imprint on local architecture and culture: Bavarian-style chalets, alpine clubs, chocolatiers, and German schools flourished—many founded or supported by German immigrants—endowing the city with a carefully maintained Central European aesthetic. Institutions such as the prestigious Primo Capraro German School, the Bariloche Andean Club, and the local classical music orchestra owe historical debts to that immigration. Thus, Bariloche was consolidated as a “civilized” and prosperous enclave in Patagonia—an alpine paradise transplanted to the end of the world.

On the other hand, this very beauty served as a screen to naturalize forgetting. The postcard of blue lakes and snow-capped peaks concealed an uncomfortable reality: “an aura of paradisiacal destination that envelops another, darker one—that of a perfect, discreet refuge for fascist fugitives.” For decades, complicity and local silence allowed these men—embodiments of twentieth-century horror—to integrate without accountability. The landscape functioned as an alibi: in such a remote and picturesque setting, their presence went unnoticed or was relativized. Only when international justice intervened (as in the Priebke case) did the bucolic façade crack to reveal the truth. Today, Bariloche even capitalizes on this hidden history through guided “Nazi tours” for tourists—but the very existence of such tours confirms how the Patagonian landscape can archive violence: beneath its natural charm lie dormant memories of complicity and pain, waiting to be told.

The Patagonian Screen as a Model of Argentine Amnesia

Across these cases—the invention of the Patagonian desert, the silent coexistence with Nazis, the tragedy of wildfires, and their cinematic reworking—a common thread emerges: the Patagonian landscape operates as a contested site of memory. Its mountains, lakes, and steppes have been used as a screen to naturalize dispossession, projecting myths of emptiness or paradise that conceal latent violence. At the same time, this landscape bears indelible traces of what occurred: it is a living archive where buried memory can resurface at any moment—whether as a historical tour, a burned forest that confronts us, or a film that reimagines the past.

The invention of the Patagonian desert, the silent coexistence with Nazis, the tragedy of wildfires, and their cinematic reworking share a truth: the Patagonian landscape operates as a contested site of memory or, to be more precise, amnesia.

Tweet

More than ever, in the face of a model that insists on repeating cycles of plunder and forgetting, Patagonia demands to be read critically. Its images—idyllic or devastated—can no longer be seen innocently; its fires cry out for ecological and territorial justice; its history calls for rewriting with the voices of the defeated; and its artistic representations invite us to remember where others would rather forget. As Schama reminds us, landscape is a work of the mind and of memory—and in the Patagonian case, that collective mind is beginning to awaken. Recognizing the violence archived beneath natural beauty is the first step toward abandoning the romanticization of the desert and beginning to heal the territory with truth and dignity. Only then can the surface of forgetting be transformed into a canvas of memory and resistance, where the landscape ceases to conceal dispossession and finally reflects justice and the diversity of its people.

Patagonia demands to be read critically. Its images—idyllic or devastated—can no longer be seen innocently; its fires cry out for ecological and territorial justice; its history calls for rewriting with the voices of the defeated; and its artistic representations invite us to remember where others would rather forget.

Tweet

My Book

Deja una respuesta