The English Version Can Be Found Scrolling Down

Mirá La Mala Educación de esta semana

Los beneficios y peligros de la invisibilidad como ciudadanía

La primera anécdota no es Gaza ni Israel ni Estados Unidos. Soy yo en el Reino Unido. Y justamente por eso importa. Mi problema “étnico” acá no adopta la forma clásica del insulto ni del desprecio abierto. No soy interpelado como “extranjero” en el sentido vulgar. Lo que aparece, primero, es la fascinación. Una fascinación irregular, intermitente, pero reconocible. Fascino porque no encajo en la narrativa dominante del inmigrante del Sur. No imito el estilo de vida inglés ni performo agradecimiento. Me considero británico en los términos poscoloniales del contrato que —en mi cabeza— creí firmar al llegar: vivir, trabajar, pensar y hablar como parte de este país, no como huésped tolerado. Esa fascinación adopta formas diversas: es sexualizante, es ejemplarizante, es curiosa. En un expediente legal reciente lo descubrí formulado de manera obscena: un paramédico, en un formulario oficial, describió mi departamento con un tono que no era técnico sino imaginario, casi literario. La palabra que usó fue “ejemplar”. Un halago pero también una ironía? Esa palabra en un documento oficial en su profunda paradoja, ejemplifica la curva, casi siempre descendente, del afecto que genero en mis conciudadanos ingleses. La fascinación, original, se agota (dura, generalmente, un año) y se transforma en desconfianza. Los chicos del café donde iba todos los días a leer y escribir durante horas —a quienes no llamaría amigos, pero sí amables— comenzaron a llamarme a mis espaldas “dodgy” (una palabra difícil de traducir y apunta a alguien que tiene algo que ocultar y no es digno de confianza absoluta). Sin ir mas lejos, mi mejor amiga terminó criminalizándome. Y ahí aparece la pregunta real: ¿miedo a qué?

La primera anécdota no es Gaza ni Israel ni Estados Unidos. Soy yo en el Reino Unido. Y justamente por eso importa. Mi problema “étnico” acá no adopta la forma clásica del insulto ni del desprecio abierto. No soy interpelado como “extranjero” en el sentido vulgar.

Tweet

El peligro de ser un enigma para un sujeto imperial cansado de sí mismo.

La respuesta no está en lo que soy, sino en lo que puedo estar ocultando. Mi alteridad es visible e invisible según yo disponga. Puedo camuflarme. Mi acento, mis modales, mi educación vivida me permiten pasar. Y justamente por eso me vuelvo sospechoso. Como los judíos en la España del siglo XV, el problema no es la diferencia evidente, sino la diferencia indetectable. El converso, el criptojudío, el que no puede ser identificado a primera vista. La alteridad que no se deja fijar. Ese es el verdadero terror teológico-político: el enemigo que puede parecer igual. Cuando bajo la guardia —o cuando decido mostrar el enigma— el enigma aparece. Y ahí la fascinación se convierte en resentimiento. Envidia, deseo desplazado, fantasía sexual. Algo profundamente neocolonial, visible en décadas de producción cultural británica —Shirley Valentine y su Grecia imaginada es un ejemplo perfecto— donde el Sur funciona como escenario de liberación para el sujeto imperial cansado de sí mismo. Pero en un contexto postimperial de fragilidad social, esa fantasía se vuelve miedo. Y el miedo necesita nombres. Entonces empiezan los ataques: sos nazi porque sos argentino; sos narco porque trabajás desde tu casa; sos sospechoso porque no tenés un trabajo de 9 a 5; sos peligroso porque no pronunciás “bien” nuestras vocales. No es racismo explícito: es criminalización preventiva. No es odio frontal: es administración del miedo. Y esa mutación —de fascinación a sospecha— es la misma lógica que organiza hoy la política global: cuando la alteridad no se puede leer, se la controla; y cuando no se la puede controlar, se la elimina.

El racismo que yo padecí y padezco no es explícito: es criminalización preventiva. No es odio frontal: es administración del miedo. Y esa mutación —de fascinación a sospecha— es la misma lógica que organiza hoy la política global: cuando el otro no es legible, se lo controla; y cuando no se lo puede controlar, se lo elimina.

Tweet

Hoy me desperté, abrí X y vi que la corresponsal de C5N —un canal pedorro, filo-kirchnerista, que todavía se autopercibe “progresista”— había sido echada por apoyar la causa palestina. No por un exabrupto, no por un error factual, no por una opinión marginal, sino por nombrar lo que ya no se puede nombrar sin castigo.

Tweet

Los Judíos Blancos, etc.

Hoy me desperté, abrí X y vi que la corresponsal de C5N —un canal pedorro, filo-kirchnerista, que todavía se autopercibe “progresista”— había sido echada por apoyar la causa palestina. No por un exabrupto, no por un error factual, no por una opinión marginal, sino por nombrar lo que ya no se puede nombrar sin castigo. Y fue en ese momento, no antes, cuando terminé de leer (mentira: abandoné conscientemente) White Jews and Us de Houria Bouteldja, un libro que me fue recomendado por Leonor Silvestri, con quien suelo erróneamente ser asociado. Un gesto típico de cierta progresía argentina que achata posiciones radicales muy distintas bajo la fantasía de que “todo lo más a la izquierda es lo mismo”. No lo es. Y justamente ahí empieza el problema. El despido en C5N y el libro de Bouteldja no están en planos separados: forman parte del mismo régimen discursivo. Un régimen donde la identidad se convierte en grilla moral, donde el conflicto material se sublima en posiciones simbólicas y donde el miedo a ser expulsado del consenso —mediático, académico o militante— produce silencio, desplazamiento o traición. La periodista es expulsada porque rompe el pacto implícito: se puede hablar de derechos humanos siempre y cuando no se toque el punto donde el progresismo occidental —y su versión periférica argentina— colisiona con sus propias alianzas geopolíticas, sus culpas históricas mal resueltas y su dependencia estructural del poder. Y el libro de Bouteldja, que parte de una intuición válida sobre el racismo europeo, fracasa exactamente en el mismo lugar: reemplaza el análisis material del poder por una economía moral de identidades que, lejos de desarmar el dispositivo, lo estabiliza. Lo que une a C5N y a Bouteldja no es la ideología explícita, sino algo más profundo: la incapacidad —o la negativa— a pensar qué ocurre cuando la política deja de ser un conflicto de relatos y pasa a ser una tecnología de administración de cuerpos, silencios y expulsiones. Ahí es donde empieza este texto. No en Gaza como metáfora, sino en el momento preciso en que decir “genocidio” deja de ser una opinión y vuelve a ser un riesgo.

La premisa central de Houria Bouteldja en White Jews and Us parte de una hipótesis potente y, a la vez, profundamente problemática: que la identidad europea moderna se construye como un dispositivo de inmunización racial, y que dentro de ese dispositivo los judíos “blancos” ocupan una posición ambigua y transaccional

Tweet

Houria Bouteldja, Leonor Silvestri y el Problema de las Feministas Renegadas

La premisa central de Houria Bouteldja en White Jews and Us parte de una hipótesis potente y, a la vez, profundamente problemática: que la identidad europea moderna se construye como un dispositivo de inmunización racial, y que dentro de ese dispositivo los judíos “blancos” ocupan una posición ambigua y transaccional. Para Bouteldja, Europa no existe como esencia sino como ficción defensiva, producida por oposición al Otro racializado; en ese esquema, el antisemitismo histórico y el filosemitismo contemporáneo no son opuestos morales sino dos momentos de una misma lógica. El primero expulsa al judío por exceso de diferencia; el segundo lo integra condicionalmente en tanto judío blanqueado, a cambio de su alineamiento —explícito o implícito— con el orden imperial occidental y, en particular, con el proyecto sionista como externalización del conflicto europeo. El problema no es solo que esta lectura tienda a homogeneizar experiencias históricas radicalmente distintas, sino que desmaterializa el pasaje decisivo del siglo XX: cuando el racismo deja de ser una tecnología de invisibilización y pasa a ser una tecnología de exterminio. En ese punto, la Shoá no puede ser leída como simple moneda moral de intercambio geopolítico sin caer en una reducción brutal de su especificidad histórica. Es acá donde suele enganchar Leonor Silvestri: su spinozismo desencantado, su rechazo frontal al reparativismo liberal y su pulsión por una ética de la potencia la llevan a coincidir con Bouteldja en la crítica a la hipocresía moral europea, pero a terminar siempre en un nihilismo furioso donde toda mediación política aparece como farsa y toda identidad como trampa. El resultado es una política que denuncia con lucidez, pero que no distingue entre dispositivos de dominación distintos ni entre posiciones materiales asimétricas; una política que confunde el desmontaje del mito europeo con la abolición de la historia concreta. Y ahí es donde mi desacuerdo con ambas aparece: porque si todo se reduce a un juego inmunitario de identidades, entonces desaparece lo que hoy es central —el apartheid, la ocupación, la desaparición administrativa— y el conflicto vuelve a resolverse en el plano simbólico, exactamente el terreno donde el poder contemporáneo ya aprendió a ganar.

El punto de contacto entre la premisa de Houria Bouteldja y la posición de Andrea Giunta no está donde suele creerse —no es Gaza, no es Israel, no es siquiera el antisemitismo— sino en algo más estructural: la sustitución de la política material por una gestión simbólica de la identidad como moneda de cambio.

Tweet

El Progresismo que perpetua el horror

El punto de contacto entre la premisa de Houria Bouteldja y la posición de Andrea Giunta no está donde suele creerse —no es Gaza, no es Israel, no es siquiera el antisemitismo— sino en algo más estructural: la sustitución de la política material por una gestión simbólica de la identidad. Bouteldja cree estar desmontando la inmunización blanca europea cuando, en realidad, acepta su marco más profundo: que la política se juega en el plano de la identidad moral y no en el de las relaciones materiales de poder. Giunta hace exactamente lo mismo desde el campo del arte, pero con un lenguaje progresista, feminista y posmoderno que resulta más digerible para el sistema cultural argentino y cierta academia identitaria. Allí donde Bouteldja habla de “judíos blancos” cooptados por Europa, Giunta habla de “escena”, “performatividad”, “opacidad” y “diva”, desplazando el conflicto fuera del terreno donde hoy se decide la vida o la muerte. En ambos casos, la identidad funciona como moneda o, mejor dicho, como commodity: algo que se intercambia, se estetiza o se problematiza discursivamente mientras el dispositivo material —el Estado, la policía, la frontera, la deportación, la desaparición— queda fuera de campo. El progresismo cultural argentino adopta esta lógica con entusiasmo porque le permite una doble ventaja: denunciar abstractamente la violencia histórica y, al mismo tiempo, no enfrentarse nunca a la violencia presente. Así, el posmodernismo llega como importación tardía y tilinga a un país donde la desaparición nunca fue metáfora, pero es usado como si lo fuera. El resultado es una cultura que se piensa radical mientras actúa como amortiguador del conflicto real: estetiza la diferencia, celebra la excepción y administra la culpa, pero no toca el régimen material que produce exclusión, persecución y terror. En ese sentido, Giunta no es una anomalía: es el síntoma más refinado de un progresismo que cree estar del lado de las víctimas porque habla su idioma, mientras contribuye a que el sistema que las produce siga funcionando sin interrupciones.

El Estado de excepción discursivo y la palabra Israel como núcleo prohibido

Tras leer X, prendí la TV y vi una entrevista reciente de Jon Stewart, uno de los presentadores más influyentes del mainstream televisivo norteamericano, judío, liberal, históricamente alineado con el Partido Demócrata, que decidió —de manera torpe, incompleta y claramente centrista— decir en voz alta algo que, sin embargo, funciona como detonador: que criticar al Estado de Israel no es lo mismo que ser antisemita, que denunciar el apartheid y la ocupación no equivale a apoyar a Hamas, y que lo que está ocurriendo en Gaza no puede seguir siendo blindado discursivamente bajo la coartada moral del combate al antisemitismo. Lo interesante no es que Stewart diga algo radical —no lo hace—, sino que el audio deja al descubierto el verdadero mecanismo disciplinario del discurso contemporáneo: la imposibilidad de analizar, contextualizar o incluso describir la violencia israelí sin antes recitar el mantra “Hamas bad” como salvoconducto moral obligatorio. En la entrevista, Stewart ironiza con precisión quirúrgica sobre ese ritual: si dependiera de ciertos sectores mediáticos, su programa entero debería consistir en repetir “Hamas bad” cada quince segundos para evitar ser acusado de complicidad con el terrorismo. Ese gesto no es humor: es diagnóstico. Lo que se revela ahí es que el verdadero tabú no es Hamas —que funciona como contraseña— sino Israel. El presentador dice algo clave: “Anti-Semitism is not the same as Zionism”, y agrega inmediatamente lo que nadie quiere admitir: “but don’t have that conversation right now”. Ese “right now” no es coyuntural, es permanente; es el estado de excepción discursivo que suspende indefinidamente la posibilidad de pensar. No se trata de proteger a judíos —de hecho, Stewart es judío— sino de proteger a un Estado de cualquier análisis material de su ejercicio del poder.

En USA, John Stewart ironiza con precisión sobre ese ritual: si dependiera de ciertos sectores mediáticos, su programa entero debería consistir en repetir “Hamas bad” cada quince segundos para evitar ser acusado de complicidad con el terrorismo.

Tweet

Por eso el escándalo no está en el contenido de lo que dice, sino en la performance y el lugar desde donde lo dice: la televisión mainstream estadounidense, no la academia, no el arte, no el activismo marginal. Ahí se ve con claridad lo que el progresismo cultural argentino no quiere ver: se pueden decir cosas mucho más radicales si se dicen en la escena correcta, con la estetización adecuada y sin consecuencias materiales; lo intolerable no es la crítica, sino la ruptura del guion. Hay un desplazamiento histórico clave: durante años, el dispositivo de silenciamiento se organizó alrededor de Hamas para bloquear cualquier discusión sobre el régimen israelí; hoy, ante la visibilidad brutal de la violencia estatal, el tabú se desplaza y lo innombrable pasa a ser Israel mismo. Nombrarlo como agente activo del poder —no como víctima eterna ni como excepción moral— se vuelve intolerable. Así, la palabra “Hamas” funciona como ritual de purificación y la palabra “Israel” como núcleo prohibido. Lo que Stewart expone, sin proponérselo del todo, es que no estamos ante un debate ideológico sino ante una tecnología de silenciamiento: no se impide hablar por censura directa, sino por la imposición de una liturgia moral que desactiva cualquier análisis antes de que empiece. Y eso conecta de lleno con todo lo anterior: con Giunta, con el progresismo cultural, con la escena como coartada, con la imposibilidad contemporánea de pensar el poder cuando el Estado deja de hablar y empieza a desaparecer cuerpos.

Lo que Stewart expone, sin proponérselo del todo, es que no estamos ante un debate ideológico sino ante una tecnología de silenciamiento: no se impide hablar por censura directa, sino por la imposición de una liturgia moral que desactiva cualquier análisis antes de que empiece. Herencia del progresismo?

Tweet

El Terror Moral Administrado

La hipótesis de Houria Bouteldja debe ser descartada. Bouteldja sostiene que el núcleo del problema contemporáneo es el filosemitismo como forma de inmunización blanca: Europa “absorbe” al judío blanco para consolidar su identidad moral y desplazar el racismo hacia otros cuerpos racializados. Esa lectura fue parcialmente pertinente en un régimen histórico donde el poder todavía necesitaba consenso simbólico, donde la legitimidad se construía mediante narrativas de inclusión, reparación y reconocimiento. Pero el presente que revelan los audios, los despidos, los silencios forzados y las autocensuras no funciona así. Hoy el problema ya no es la inmunización simbólica, sino la coerción discursiva y material. En el ecosistema en el que vivíamos, no hay amor hacia los judíos, no hay filosemitismo, no hay integración celebratoria: hay miedo. Miedo a hablar. Miedo a nombrar el apartheid. Miedo a perder el trabajo, como le ocurrió a la periodista de C5N. Miedo a ser señalado, cancelado, expulsado del circuito profesional. Eso no es filosemitismo: es terror moral administrado, una tecnología de silenciamiento que no busca incluir identidades sino bloquear análisis. Bouteldja se equivoca porque sigue leyendo el conflicto como una disputa entre identidades —judíos blancos, europeos, racializados— cuando lo que tenemos enfrente es algo mucho más brutal y menos simbólico: una arquitectura estatal y geopolítica de apartheid, ocupación y exterminio por asedio, sostenida no por amor ni por consenso, sino por disciplinamiento, chantaje y miedo. Leer este escenario en clave identitaria no solo es insuficiente: es funcional al dispositivo que pretende denunciar.

Bouteldja se equivoca porque sigue leyendo el conflicto como una disputa entre identidades —judíos blancos, europeos, racializados— cuando lo que tenemos enfrente es algo mucho más brutal: una arquitectura estatal y geopolítica de apartheid, ocupación y exterminio por asedio, sostenida por consenso, disciplinamiento, chantaje y miedo.

Tweet

La Shoah como el momento en el que ser invisible dejo de ser posible

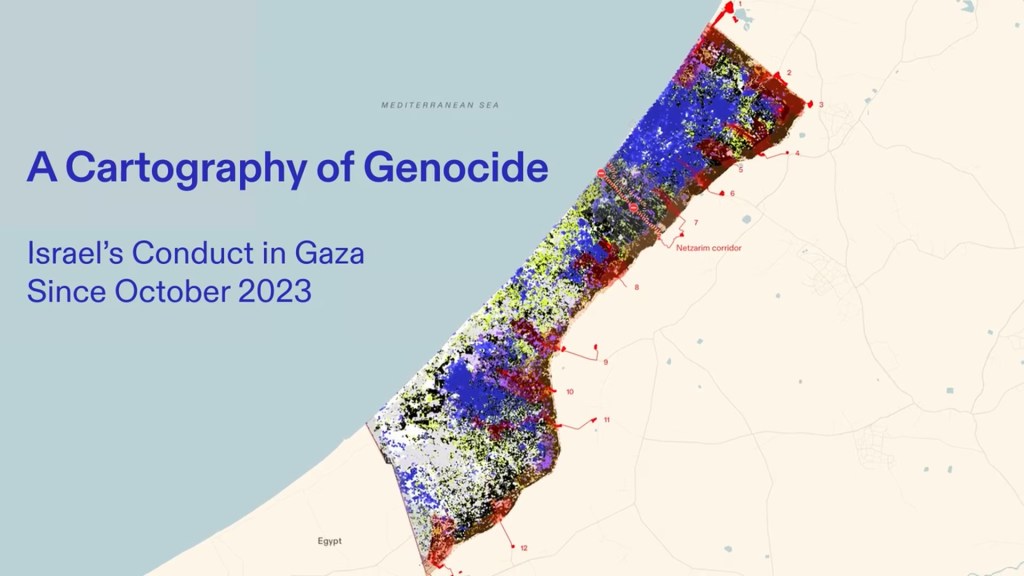

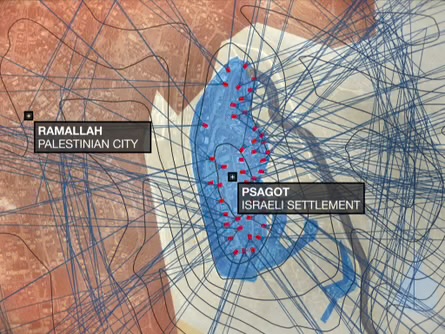

Pero hay una distinción que Houria Bouteldja no llega a formular: invisibilidad no es raza, y desaparición no es desplazamiento. La Shoah no fue simplemente “racismo llevado al extremo”, sino el momento histórico en el que la invisibilidad —que antes podía funcionar como camuflaje o protección precaria— pasa a operar como justificación de la eliminación. No se mata a pesar de que el cuerpo no sea visible; se mata porque no lo es, porque no deja rastro, porque puede ser borrado sin ruido. Y ahí está la clave para entender el presente. Gaza Strip no funciona como Auschwitz —no hay hornos, no hay industria de exterminio—, pero sí como una ciudad medieval sitiada: corte de agua, de alimentos, de electricidad, de movilidad, de horizonte temporal. Un asedio prolongado que administra la muerte por agotamiento, por hambre, por asfixia, por imposibilidad de futuro. Eso no se explica en términos de identidad ni de reconocimiento simbólico. Se explica por poder imperial y colonial, ejercido por un Estado que se piensa a sí mismo como laico, moderno y moralmente excepcional. Ahí está el límite del marco de Bouteldja: Israel no opera como una “minoría cooptada por Europa” ni como un sujeto inmunizado por filosemitismo blanco, sino como un Estado soberano armado, con doctrina militar, territorio, ejército, aliados estratégicos y una lógica imperial plenamente desplegada. Insistir en leer este escenario como un problema de identidades es no ver —o no querer ver— que lo que está en juego ya no es la inclusión simbólica de un cuerpo, sino la administración sistemática de su desaparición.

Gaza Strip no funciona como Auschwitz —no hay hornos, no hay industria de exterminio—, pero sí como una ciudad medieval sitiada: corte de agua, de alimentos, de electricidad, de movilidad, de horizonte temporal. Un asedio prolongado que administra la muerte por agotamiento, por hambre, por asfixia, por imposibilidad de futuro.

Tweet

El Apartheid no solo destruye a los Palestinos sino también a los ciudadanos de Israel

El punto del “love” es, efectivamente, el más débil —y el más peligroso— del planteo de Houria Bouteldja, porque en el contexto actual su “revolutionary love” como solución, se vuelve una obscenidad teórica: no porque el amor sea algo despreciable, sino porque los valores no son neutros, las identidades producen efectos materiales, y ninguna ética puede reemplazar el análisis concreto del poder. Esto yo lo veo en mi vida sexual: no existe una ética universal del deseo —nadie puede imponerse amar todo cuerpo para ser moralmente correcto— y del mismo modo no existe una ética política abstracta que pueda ignorar quién controla tanques, drones, fronteras, cielos y checkpoints. El amor no redistribuye asimetrías militares, no desmantela regímenes, no detiene asedios. El apartheid no solo destruye a los palestinos, también corroe a la sociedad israelí, como todo régimen fascista termina dañando a quienes dice proteger, deformando subjetividades, produciendo paranoia, violencia y empobrecimiento moral. Eso no se corrige con afecto ni con reconciliaciones simbólicas, sino con la desarticulación material del dispositivo de dominación. Hablar de amor en este escenario no es radicalidad: es una forma sofisticada de despolitizar la violencia, de desplazar el conflicto desde la estructura hacia la conciencia, desde el poder hacia la virtud. Y ahí, el discurso deja de ser emancipatorio para volverse funcional.

El Apartheid no solo destruye a los Palestinos sino también a los ciudadanos de Israel

Tweet

El fin de la inocencia

El problema ya no es identitario ni moral, es estatal y material. Lo que ocurre hoy en Gaza no puede seguir pensándose como “conflicto”, ni lo que hace Israel como una “democracia hipotecada”. Se trata de un régimen de apartheid y asedio, sostenido por un Estado soberano con ejército, aliados, control territorial y capacidad de administrar la desaparición. Cuando se dice esto, el campo discursivo se ordena de inmediato: se entiende por qué se echan periodistas que usan la palabra genocidio, por qué los medios progresistas retroceden, por qué el mantra “Hamas bad” es obligatorio y por qué toda discusión es desviada hacia la ética y el escándalo performativo. No es censura blanda ni malentendido cultural: es terror moral administrado. En ese contexto, la hipótesis de Bouteldja fracasa porque sigue leyendo el problema como disputa de identidades y afectos —filosemitismo, amor, reconocimiento— cuando lo que está en juego es poder de Estado, soberanía armada y exterminio por asedio. No hay libertad de análisis donde hay miedo a hablar; no hay debate democrático donde hay apartheid; y no hay inocencia posible en un progresismo cultural que, en lugar de romper ese dispositivo, lo administra, usando al morocho oportunista disponible a cambio de unos mangos: La Chola Poblete, la SIDE, ICE, etc.

En medio del terror moral administrado en el que vivimos no hay libertad de análisis donde se teme hablar; no hay inocencia posible en un progresismo cultural que, en lugar de romper ese dispositivo, lo administra, usando al morocho oportunista disponible a cambio de unos mangos: La Chola Poblete, la SIDE, ICE, etc.

Tweet

© Dr. Rodrigo Cañete, 2026. All rights reserved. Reproduction without permission is prohibited.

Gaza: Genocide and Apartheid — How the Israeli State Exterminates Palestinians and Erodes Its Own Society

The Slippery Postcolonial Contract I Believed I Signed by Choosing to Live in the UK

The first anecdote is not Gaza, nor Israel, nor the United States. It is me, in the United Kingdom. And precisely for that reason, it matters. My “ethnic” problem here does not take the classic form of insult or open contempt. I am not addressed as a “foreigner” in the vulgar sense. What appears first is fascination. An irregular, intermittent fascination, but a recognizable one. I fascinate because I do not fit the dominant narrative of the Southern immigrant. I do not imitate the English lifestyle, nor do I perform gratitude. I consider myself British in the postcolonial terms of the contract that—at least in my head—I believed I had signed upon arriving: to live, work, think, and speak as part of this country, not as a tolerated guest. That fascination takes different forms: it is sexualizing, exemplary, curious. I recently discovered it articulated in an obscene way in a legal file: a paramedic, in an official form, described my flat in a tone that was not technical but imaginary, almost literary. The word he used was “exemplary.” A compliment, perhaps—but also an irony. That word, appearing in an official document with all its paradox, perfectly illustrates the curve—almost always a descending one—of the affect I generate among my English fellow citizens. The initial fascination wears off (it usually lasts about a year) and turns into distrust. The guys at the café where I went every day to read and write for hours—whom I would not call friends, but certainly friendly—began calling me “dodgy” behind my back (a hard word to translate, suggesting someone who has something to hide and is not entirely trustworthy). Not to go any further, my best friend ended up criminalizing me. And that is where the real question appears: afraid of what?

The Danger of Being an Enigma to an Imperial Subject Tired of Itself

The answer does not lie in what I am, but in what I might be hiding. My alterity is visible and invisible depending on how I choose to deploy it. I can camouflage myself. My accent, my manners, my lived education allow me to pass. And precisely for that reason, I become suspect. As with Jews in fifteenth-century Spain, the problem is not evident difference, but undetectable difference. The convert, the crypto-Jew, the one who cannot be identified at first glance. Alterity that refuses to be fixed. That is the true theological-political terror: the enemy who can appear the same. When I lower my guard—or when I choose to reveal the enigma—the enigma appears. And that is when fascination turns into resentment. Envy, displaced desire, sexual fantasy. Something profoundly neocolonial, visible in decades of British cultural production—Shirley Valentine and its imagined Greece is a perfect example—where the South functions as a stage of liberation for an imperial subject exhausted by itself. But in a post-imperial context of social fragility, that fantasy turns into fear. And fear needs names. Then the attacks begin: you’re a Nazi because you’re Argentine; you’re a drug dealer because you work from home; you’re suspicious because you don’t have a 9-to-5 job; you’re dangerous because you don’t pronounce “our” vowels properly. This is not explicit racism: it is preventive criminalization. It is not frontal hatred: it is the administration of fear. And that mutation—from fascination to suspicion—is the very logic that organizes global politics today: when alterity cannot be read, it is controlled; and when it cannot be controlled, it is eliminated.

When I lower my guard—or when I choose to reveal the enigma—the enigma appears. And that is when fascination turns into resentment. Envy, displaced desire, sexual fantasy. Something profoundly neocolonial, visible in decades of British cultural production—Shirley Valentine and its imagined Greece is a perfect example—where the South functions as a stage of liberation for an imperial subject exhausted by itself.

Tweet

White Jews, Etc.

Today I woke up, opened X, and saw that the correspondent for C5N—a shabby, filo-Kirchnerist channel that still self-identifies as “progressive”—had been fired for supporting the Palestinian cause. Not for an outburst, not for a factual error, not for a marginal opinion, but for naming what can no longer be named without punishment. And it was at that moment, not before, that I finished reading (a lie: I consciously abandoned) White Jews and Us by Houria Bouteldja, a book recommended to me by Leonor Silvestri, with whom I am often mistakenly associated. A typical gesture of a certain Argentine progressivism that flattens very different radical positions under the fantasy that “everything on the far left is the same.” It is not. And that is precisely where the problem begins.

The firing at C5N and Bouteldja’s book do not belong to separate planes: they are part of the same discursive regime. A regime in which identity becomes a moral grid, in which material conflict is sublimated into symbolic positions, and in which fear of being expelled from consensus—media, academic, or militant—produces silence, displacement, or betrayal. The journalist is expelled because she breaks an implicit pact: one may speak of human rights as long as one does not touch the point where Western progressivism—and its peripheral Argentine version—collides with its own geopolitical alliances, its unresolved historical guilt, and its structural dependence on power. And Bouteldja’s book, which begins from a valid intuition about European racism, fails at exactly the same point: it replaces a material analysis of power with a moral economy of identities that, far from dismantling the dispositif, stabilizes it.

What unites C5N and Bouteldja is not explicit ideology, but something deeper: the inability—or the refusal—to think through what happens when politics ceases to be a conflict of narratives and becomes a technology for the administration of bodies, silences, and expulsions. That is where this text begins. Not in Gaza as a metaphor, but in the precise moment when saying “genocide” ceases to be an opinion and becomes a risk.

The central premise of Houria Bouteldja in White Jews and Us begins from a powerful yet deeply problematic hypothesis: that modern European identity is constructed as a device of racial immunization, and that within this device “white” Jews occupy an ambiguous and transactional position.

Tweet

Houria Bouteldja and the Problem of Renegade Feminists

The central premise of Houria Bouteldja in White Jews and Us begins from a powerful yet deeply problematic hypothesis: that modern European identity is constructed as a device of racial immunization, and that within this device “white” Jews occupy an ambiguous and transactional position. For Bouteldja, Europe does not exist as an essence but as a defensive fiction, produced in opposition to the racialized Other; within this framework, historical antisemitism and contemporary philo-Semitism are not moral opposites but two moments of the same logic. The former expels the Jew for an excess of difference; the latter conditionally integrates them as a whitened Jew, in exchange for their explicit or implicit alignment with the Western imperial order and, in particular, with the Zionist project as an externalization of Europe’s internal conflict.

The problem is not only that this reading tends to homogenize radically different historical experiences, but that it dematerializes the decisive passage of the twentieth century: the moment when racism ceases to be a technology of invisibilization and becomes a technology of extermination. At that point, the Shoah cannot be read as a simple moral currency of geopolitical exchange without collapsing its historical specificity into a brutal reduction. This is where Leonor Silvestri often enters the picture: her disenchanted Spinozism, her outright rejection of liberal reparativism, and her drive toward an ethics of potency lead her to converge with Bouteldja in the critique of European moral hypocrisy, only to end repeatedly in a furious nihilism in which all political mediation appears as farce and all identity as trap.

The result is a politics that denounces with clarity but fails to distinguish between different dispositifs of domination or between materially asymmetric positions; a politics that confuses the dismantling of the European myth with the abolition of concrete history. And this is where my disagreement with both becomes clear: because if everything is reduced to an immunitary play of identities, then what is central today disappears—apartheid, occupation, administrative disappearance—and the conflict is once again resolved on the symbolic plane, precisely the terrain on which contemporary power has already learned how to win.

Bouteldja’s thesis is problematic because if everything (White Europe, in this case) is reduced to an immunitary play of identities, then what is central today disappears—apartheid, occupation, administrative disappearance—and the conflict is once again resolved on the symbolic plane, precisely the terrain on which contemporary power has already learned how to win.

Tweet

Progressivism That Perpetuates Horror

The point of contact between Houria Bouteldja’s premise and Andrea Giunta’s position is not where it is usually assumed to be—not Gaza, not Israel, not even antisemitism—but something more structural: the substitution of material politics with a symbolic management of identity. Bouteldja believes she is dismantling European white immunization when, in fact, she accepts its deepest framework: that politics is played out on the plane of moral identity rather than on that of material relations of power. Giunta does exactly the same from the field of art, but with a progressive, feminist, and postmodern language that is far more digestible for the Argentine cultural system and a certain strain of identitarian academia. Where Bouteldja speaks of “white Jews” co-opted by Europe, Giunta speaks of “scene,” “performativity,” “opacity,” and “diva,” displacing the conflict away from the terrain where life and death are decided today. In both cases, identity functions as currency—or rather, as a commodity: something that is exchanged, aestheticized, or discursively problematized while the material apparatus—the state, the police, the border, deportation, disappearance—remains out of frame. Argentine cultural progressivism adopts this logic enthusiastically because it offers a double advantage: it allows one to denounce historical violence in the abstract while never having to confront present violence. Thus, postmodernism arrives as a late and frivolous import to a country where disappearance was never a metaphor, yet is treated as if it were one. The result is a culture that imagines itself radical while acting as a shock absorber for real conflict: it aestheticizes difference, celebrates the exception, and manages guilt, but never touches the material regime that produces exclusion, persecution, and terror. In this sense, Giunta is not an anomaly; she is the most refined symptom of a progressivism that believes it stands with the victims because it speaks their language, while simultaneously helping ensure that the system that produces them continues to function without interruption.

The Discursive State of Exception and the Word “Israel” as a Forbidden Core

After reading X, I turned on the TV and watched a recent interview with Jon Stewart, one of the most influential presenters in American mainstream television—Jewish, liberal, historically aligned with the Democratic Party—who decided, in a clumsy, incomplete, and clearly centrist way, to say out loud something that nevertheless functions as a detonator: that criticizing the State of Israel is not the same as being antisemitic, that denouncing apartheid and occupation is not equivalent to supporting Hamas, and that what is happening in Gaza cannot continue to be discursively shielded under the moral pretext of fighting antisemitism. What is interesting is not that John Stewart says something radical—he does not—but that he allows to see the true disciplinary mechanism of contemporary discourse: the impossibility of analyzing, contextualizing, or even describing Israeli violence without first reciting the mantra “Hamas bad” as an obligatory moral safe-conduct. In the interview, Stewart ironizes with surgical precision about this ritual: if it were up to certain media sectors, his entire show would have to consist of repeating “Hamas bad” every fifteen seconds to avoid being accused of complicity with terrorism. That gesture is not humor; it is diagnosis. What is revealed there is that the real taboo is not Hamas—which functions as a password—but Israel. The host says something crucial: “Anti-Semitism is not the same as Zionism,” and immediately adds what no one wants to admit: “but don’t have that conversation right now.” That “right now” is not contingent; it is permanent. It is the discursive state of exception that indefinitely suspends the possibility of thought. This is not about protecting Jews—Stewart himself is Jewish—but about protecting a state from any material analysis of its exercise of power. That is why the scandal lies not in the content of what he says, but in the performance and the place from which he says it: American mainstream television, not academia, not art, not marginal activism. There, one can see clearly what Argentine cultural progressivism refuses to see: far more radical things can be said if they are said in the correct scene, with the proper aestheticization, and without material consequences; what is intolerable is not critique, but the rupture of the script. The audio also reveals a key historical displacement: for years, the silencing apparatus was organized around Hamas to block any discussion of the Israeli regime; today, faced with the brutal visibility of state violence, the taboo shifts and the unnameable becomes Israel itself. Naming it as an active agent of power—not as an eternal victim nor as a moral exception—becomes intolerable. Thus, the word “Hamas” functions as a ritual of purification, and the word “Israel” as a forbidden core. What Stewart exposes, without fully intending to, is that we are not facing an ideological debate but a technology of silencing: speech is not prevented by direct censorship, but by the imposition of a moral liturgy that deactivates any analysis before it can begin. And this connects directly with everything that precedes it: with Giunta, with cultural progressivism, with the scene as alibi, with the contemporary inability to think power when the state stops speaking and begins to make bodies disappear.

What is interesting is not that John Stewart says something radical like that what is going on Gaza is a genocide—he does not—but that he allows to see the true disciplinary mechanism of contemporary discourse: the impossibility of describing Israeli violence without first reciting the mantra “Hamas bad!” as an obligatory moral safe-conduct.

Tweet

Administered Moral Terror

Houria Bouteldja’s hypothesis must be discarded. Bouteldja argues that the core of the contemporary problem is philo-Semitism as a form of white immunization: Europe “absorbs” the white Jew in order to consolidate its moral identity and displace racism onto other racialized bodies. That reading was partially pertinent within a historical regime in which power still required symbolic consensus, where legitimacy was built through narratives of inclusion, repair, and recognition. But the present revealed by the audios, the firings, the enforced silences, and the pervasive self-censorship does not function that way. Today, the problem is no longer symbolic immunization but discursive and material coercion. In the ecosystem we inhabit, there is no love for Jews, no philo-Semitism, no celebratory integration: there is fear. Fear of speaking. Fear of naming apartheid. Fear of losing one’s job, as happened to the journalist at C5N. Fear of being singled out, canceled, expelled from professional circuits. That is not philo-Semitism; it is administered moral terror—a technology of silencing that does not seek to include identities but to block analysis. Bouteldja is mistaken because she continues to read the conflict as a dispute between identities—white Jews, Europeans, racialized subjects—when what stands before us is far more brutal and far less symbolic: a state and geopolitical architecture of apartheid, occupation, and extermination by siege, sustained not by love or consensus but by discipline, blackmail, and fear. Reading this scenario through an identitarian lens is not only insufficient; it is functional to the very apparatus it claims to denounce.

Today, the problem is no longer symbolic immunization but discursive and material coercion. In the ecosystem we inhabit, there is no love for Jews, no philo-Semitism, no celebratory integration: there is fear. Fear of speaking. Fear of naming apartheid. Fear of losing one’s job,

Tweet

The Shoah as the Moment When Invisibility Ceased to Be Possible

But there is a distinction that Houria Bouteldja fails to articulate: invisibility is not race, and disappearance is not displacement. The Shoah was not simply “racism taken to its extreme,” but the historical moment in which invisibility—previously capable of functioning as camouflage or as a fragile form of protection—became a justification for elimination. People were not killed despite their bodies being invisible; they were killed because they were invisible, because they left no trace, because they could be erased without noise. And this is the key to understanding the present. The Gaza Strip does not function like Auschwitz—there are no ovens, no industrial machinery of extermination—but it does function like a besieged medieval city: the cutting off of water, food, electricity, mobility, and temporal horizon. A prolonged siege that administers death through exhaustion, hunger, suffocation, and the impossibility of a future. This cannot be explained in terms of identity or symbolic recognition. It can only be explained through imperial and colonial power, exercised by a state that understands itself as secular, modern, and morally exceptional. Here lies the limit of Bouteldja’s framework: Israel does not operate as a “minority co-opted by Europe,” nor as a subject immunized by white philo-Semitism, but as an armed sovereign state, with military doctrine, territory, an army, strategic allies, and a fully deployed imperial logic. To persist in reading this scenario as a problem of identities is to fail—or to refuse—to see that what is now at stake is no longer the symbolic inclusion of a body, but the systematic administration of its disappearance.

The Gaza Strip does not function like Auschwitz—there are no ovens, no industrial machinery of extermination—but it does function like a besieged medieval city: the cutting off of water, food, electricity, mobility, and temporal horizon. A prolonged siege that administers death through exhaustion, hunger, suffocation, and the impossibility of a future.

Tweet

The problem is no longer identitarian or moral; it is state-based and material. What is happening today in Gaza can no longer be understood as a “conflict,” nor can Israel’s actions be framed as those of a “compromised democracy.” This is a regime of apartheid and siege, sustained by a sovereign state with an army, allies, territorial control, and the capacity to administer disappearance.

Tweet

It Cuts Both Ways

The problem is no longer identitarian or moral; it is state-based and material. What is happening today in Gaza can no longer be understood as a “conflict,” nor can Israel’s actions be framed as those of a “compromised democracy.” This is a regime of apartheid and siege, sustained by a sovereign state with an army, allies, territorial control, and the capacity to administer disappearance. Once this is said, the discursive field immediately falls into place: it becomes clear why journalists are fired for using the word genocide, why progressive media retreat, why the mantra “Hamas bad” is compulsory, and why every discussion is diverted toward ethics and performative scandal. This is not soft censorship or cultural misunderstanding; it is administered moral terror. In this context, Bouteldja’s hypothesis collapses because it continues to read the problem as a dispute over identities and affects—philo-Semitism, love, recognition—when what is at stake is state power, armed sovereignty, and extermination by siege. The audio proves this with clarity: there is no freedom of analysis where there is fear of speaking; there is no democratic debate where there is apartheid; and there is no possible innocence in a cultural progressivism that, instead of breaking this dispositif, manages it.

Once the truth is said, the discursive field immediately falls into place: it becomes clear why journalists are fired for using the word genocide, why progressive media retreat, why the mantra “Hamas bad” is compulsory, and why every discussion is diverted toward ethics and performative scandal. This is not soft censorship or cultural misunderstanding; it is administered moral terror

Tweet

© Dr. Rodrigo Cañete, 2026. All rights reserved. Reproduction without permission is prohibited.

Mi libro está publicado por Penguin está disponible en librerías, Mercado Libre y Amazon.

Subscribite a mi Canal de YouTube.

Deja una respuesta