The English Version Can Be Found Scrolling Down

Retraumatización

Antes de ayer, en las calles de Minneapolis algo que ya estaba roto se cristalizó ante los ojos de todo el mundo para instalar el horror, de manera logísticamente más barata que un ataque a una colonia Danesa. Alex Pretti, de 37 años, un enfermero no racializable (lo que, lamentablemente, puede funcionar aún como fuente de justificación en Estados Unidos), conocido localmente por cuidar veteranos, fue asesinado a tiros por agentes federales durante una operación de inmigración en medio de protestas en esa ciudad. Como es bien sabido, en una escalada de indignidad, la versión oficial del Departamento de Seguridad Nacional de la Casa Blanca lo presentó como una amenaza, pero los videos muestran lo contrario. Ese contraste visual es el eje del trauma. La indignación se transformó en bronca y detonó vigilias y un ciclo de indignación pública. Pretty murió defendiendo a alguien que necesitaba ayuda. Murió en su ley y eso lo convierte en algo que, en la tradición cristiana, suele llamarse “mártir” y en la laica, un “gentleman”. Un hombre gentil. Esto es un grave error de calculo del Gobierno Federal.

Antes de ayer, en Minneapolis un enfermero no racializable conocido localmente por cuidar veteranos, fue asesinado por agentes federales y pocos minutos después la Casa Blanca lo presentó como una amenaza, pero los videos muestran lo contrario. Ese contraste visual es el eje del trauma social de la clase media norteamericana, hoy.

Tweet

Se pretendió que Minnesota fuera un caso paradigmático. Una ciudad relativamente pequeña y controlable por la fuerza fue elegida por el regimen dictatorial Trumpiano para ser víctima de una operación de alteración del regimen de percepción de la ciudadanía. Lo que muchos vieron como una garantía que es la posibilidad de filmar los hechos es precisamente lo que el gobierno pretendía. No solo normalizar la violencia estatal, sino moldar la forma en que la sociedad percibe esa violencia. Es aquí donde la experiencia de la dictadura militar Argentina y de su realidad actual bajo Javier Milei es relevante.

Se pretendió que Minnesota fuera un caso paradigmático. Una ciudad relativamente pequeña y controlable por la fuerza fue elegida por el regimen dictatorial Trumpiano para ser eje de un experimento de alteración del regimen de percepción de la ciudadanía.

Tweet

Para eso vale la pena retomar el concepto que desarrolla Diana Taylor sobre el percepticidio —no simplemente la eliminación física de cuerpos o derechos, sino la destrucción de la capacidad colectiva de ver y nombrar lo que está ocurriendo—, que fue central en la lógica de terrorismo de Estado en Argentina durante los setentas y forma parte del repertorio performativo de la represión moderna. Percepticidio es la operación por la cual el terror deja de ser visible como tal, incluso cuando sucede a plena luz del día, y se vuelve ‘invisible’. Para Taylor, los argentinos no podemos ver lo que tenemos frente a nosotros.

Percepticidio es la operación por la cual el terror deja de ser visible como tal, incluso cuando sucede a plena luz del día, y se vuelve ‘invisible’. Para Taylor, los argentinos no podemos ver lo que tenemos frente a nosotros.

Tweet

Reality TV Star vs el Milei Escondido

En Estados Unidos, sin embargo, la estrategia viene de una estrella de reality TV que demanda que nada se esconda, incluso la violencia extrema. El martiricidio en Minnesota se convierte en parte de una narrativa en la que el Estado federal despliega fuerza de manera visible, y con alto impacto mediático. Esto no busca desaparecer cuerpos en la sombra, sino modelar la percepción colectiva para que la violencia sea, como el ghost in the machine, real e irreal, al mismo tiempo. Y, como todo meme, ese tipo de espectro es gestionable y percibido como inevitable sino se siguen ciertas reglas que, ademas, jamás son enunciadas.

Minnesota, sin embargo, es una ciudad que conservo los ideales Tocquevillianos pero procesados por la experiencia Rooseveltiana y sospecho que también por las condiciones climáticas extremas y ni hablar de su pasado represivo con el asesinato de George Floyd. Redes de ciudadanos que no estaban allí por motivos raciales ni sectarios ni de clase sino por empatía comunitaria, transformaron a la ciudad en un espejo involuntario que hace que el resto del mundo se vea reflejado y sienta, en algun lugar de su psiquis, un poco de envidia y verguenza. Minnesota es la ciudad que desvela pero también complica la ficción del “orden civil” y muestra la brutalidad estatal sin anestesia.

Minnesota, sin embargo, es una ciudad que conservo los ideales Tocquevillianos tras el asesinato de George Floyd. Redes de ciudadanos se ayudan anónimamente por empatía comunitaria, Minnesota es la ciudad que desvela pero también complica la ficción del “orden civil” y muestra la brutalidad estatal sin anestesia. Y nos debería dar envidia.

Tweet

Hipervisibilidad de Shock USA vs Hipocresía Argentina

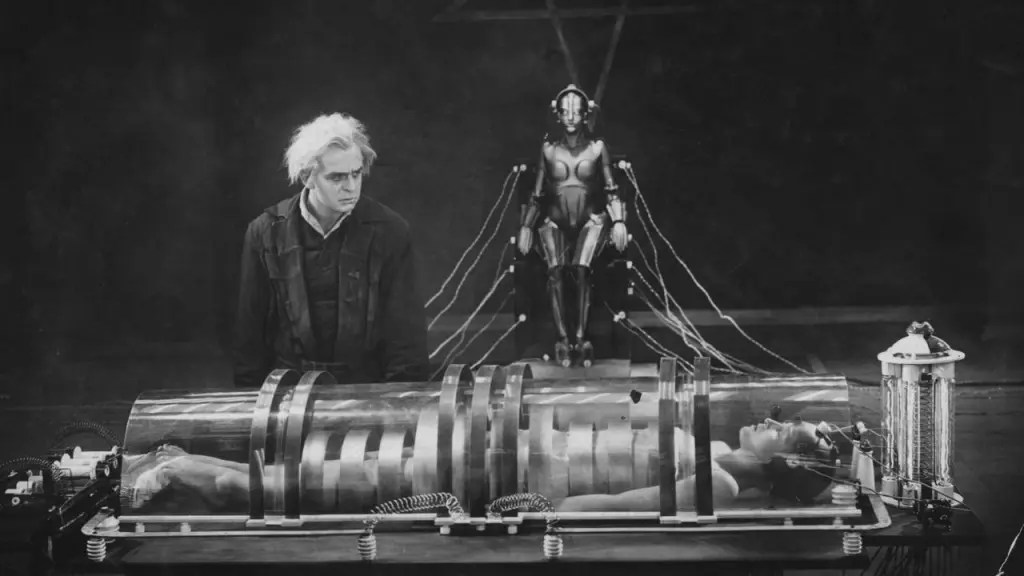

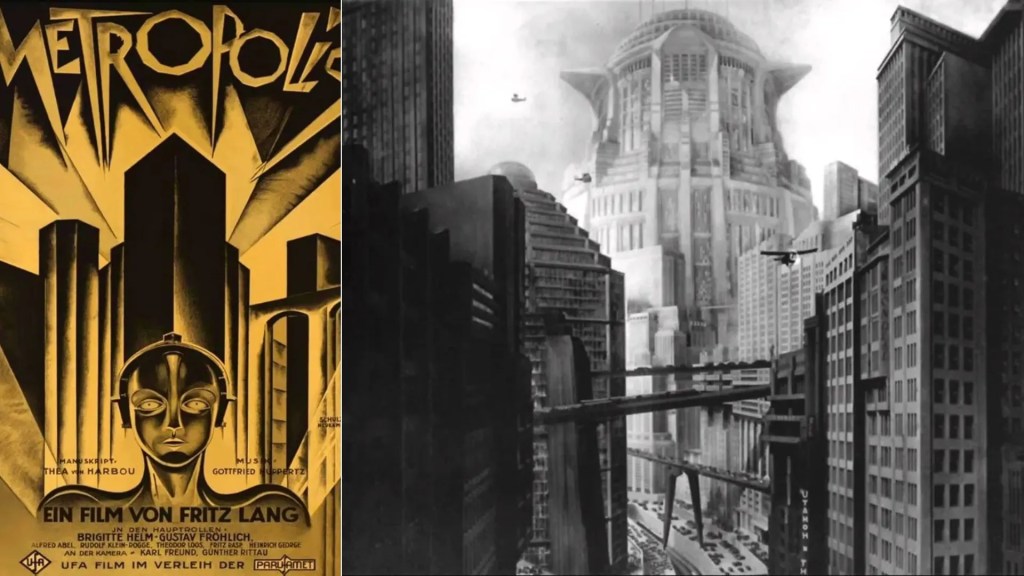

Esa politica TRUMPIANA de visibilidad brutal contrasta con la cultural hipocresia Argentina. Lo que digo no es moralizante sino el resultado del eficaz trabajo “percepticida” hecho, desde el Estado terrorista, hace décadas. El terror se estructuró como algo invisible, fragmentado, burocrático y negable y la falta de empatía oscila bipolarmente entre la performance de un falso amor comunitario y el desprecio violento del vecino. La Argentina ha sido desde las Juntas algo comparable a la película Metrópolis de Fritz Lang. Las desapariciones no se anunciaban en las plazas, sino que se ocultaban en papeles legales, archivos oficiales cerrados, órdenes no accesibles, “causas sin responsables” y un aparato estatal que aprendió a borrar su propia huella. En tiempos democráticos, la política del terror se practica desde la invisibilidad del aparato, desde la opacidad normativa, la clasificación de información, la ausencia de rendición de cuentas y la negación práctica de la visibilidad judicial o pública del proceso de represión. Esto, mientras, hasta hace poco, las manifestaciones eran toleradas y hasta celebradas como banal fiesta publica.

Esa politica TRUMPIANA de visibilidad brutal contrasta con la historica hipocresía cultural Argentina; resultado del eficaz trabajo “percepticida” hecho, desde el Estado terrorista, desde hace décadas. La falta de empatía oscila bipolarmente entre la performance de un falso amor comunitario y el desprecio violento del vecino y el terror.

Tweet

El decreto publicado en el Boletín Oficial hace un par de semanas por Javier Milei no crea formalmente una “fuerza paramilitar” como Trump, pero reorganiza y amplía de manera significativa las facultades del sistema de inteligencia y seguridad del Estado, bajo el lenguaje técnico de la “prevención”, la “anticipación de amenazas” y la “protección del orden democrático”. En términos concretos, el decreto flexibiliza los límites entre inteligencia criminal, inteligencia estratégica e intervención operativa, habilitando a los organismos a recolectar, procesar y cruzar información sobre personas, organizaciones y dinámicas sociales sin que medie necesariamente una orden judicial clara y específica. Al hacerlo, desdibuja la frontera entre investigación y acción, entre análisis y ejecución, y concentra poder discrecional en agencias que históricamente han operado con baja transparencia y escaso control civil efectivo. No se trata de una ruptura abrupta del Estado de derecho, en un país en el que el Poder Judicial es mucho mas poroso que el norteamericano, sino de algo más peligroso: una normalización administrativa de la excepción, donde la legalidad funciona como cobertura formal para prácticas que pueden derivar en vigilancia masiva, persecución selectiva y, en el extremo, en mecanismos de neutralización extrajudicial. En un país con una historia concreta de terrorismo de Estado, este tipo de decretos no inaugura el problema, pero reactiva una arquitectura institucional ya conocida, donde la violencia no necesita mostrarse para operar porque su eficacia depende precisamente de su opacidad.

Milei como Maestro de Trump

Milei se puede dar ese lujo y no apostar tan fuerte como Trump en su proyecto de tiranía institucionalizada porque la Argentina ya es “percepticida”. La desaparición no necesita escenografía, porque la invisibilidad institucional ya está internalizada en la conducta ciudadana. El decreto no impacta los sentidos de la población porque la violencia estatal —su forma, su modo, su gestión— ya opera en un régimen donde las cámaras de teléfonos, las protestas callejeras y los estándares públicos de vigilancia no acceden al núcleo real de decisiones de poder. La violencia no tiene que mostrarse para existir; está estructuralmente incrustada en lo que no se ve.

En Argentina, la violencia no tiene que mostrarse para existir; está estructuralmente incrustada en lo que no se ve. No se busca escandalizar, sino neutralizar la posibilidad misma de percepción critica. En este sentido, Milei no es el alumno de Trump sino, muy por el contrario, su maestro.

Tweet

De allí que la estrategia “pseudo-trumpiana” del gobierno de Milei no se parezca a la de Trump en su modo de operar. En Estados Unidos la estrategia de shock visual busca imponer una narrativa de fuerza: la violencia explícita, la presencia de agentes en las calles, los tiroteos filmados, las detenciones públicas. En Argentina, el terror se administra desde la capa invisible del sistema, desde decretos, reglamentos, aparatos administrativos, jurisdicciones de inteligencia que nunca se muestran en acción pública. No se busca escandalizar, sino neutralizar la posibilidad misma de percepción critica. En este sentido, Milei no es el alumno de Trump sino, muy por el contrario, su maestro.

En Argentina el desafío perceptivo es interno y estructural: la política y el público han aprendido a no ver lo que ocurre detrás de la cortina institucional. El choque de ambos modelos —visibilidad versus invisibilidad— nos obliga a repensar no solo qué violencia se ejerce, sino cómo se administra la percepción de esa violencia.

En Argentina el desafío perceptivo es interno y estructural: la política y el público han aprendido a no ver lo que ocurre detrás de la cortina institucional. El choque de ambos modelos —visibilidad versus invisibilidad— nos obliga a repensar no solo qué violencia se ejerce, sino cómo se administra la percepción de esa violencia.

Tweet

Mientras el mundo inflama su atención en lo que ocurre en Minneapolis, en Argentina el peligro es que la violencia estatal se intensifique, operando en la zona de invisibilidad donde pocas cámaras, pocos juicios, pocos discursos penetran. Comprender esto no es una abstracción, sino un paso para recuperar no solo la memoria, sino la capacidad de ver y nombrar lo que está sucediendo ahora, aquí y en todas partes.

The Martyrdom of Alex Petti in Minneapolis Reveals Trump as a Clumsy Student of Javier Milei (ENG)

Mistake or Error?

The day before yesterday, in the streets of Minneapolis, something that was already broken crystallised before the eyes of the entire world in order to install horror, in a way that was logistically cheaper than an attack on a Danish colony. Alex Pretti, 37 years old, a non-racializable nurse (which, unfortunately, can still function as a source of justification in the United States), known locally for caring for veterans, was shot dead by federal agents during an immigration operation amid protests in that city. As is well known, in an escalation of indignity, the official version from the White House Department of Homeland Security portrayed him as a threat, but the videos show the opposite. That visual contrast is the axis of the trauma. Indignation turned into rage and triggered vigils and a cycle of public outrage. Pretti died defending someone who needed help. He died according to his principles, and that turns him into something that, in the Christian tradition, is usually called a “martyr” and, in the secular one, a “gentleman.” A gentle man. This is a serious miscalculation by the Federal Government.

The day before yesterday, in Minneapolis, Alex Pretti, a non-racializable nurse known locally for caring for veterans, was shot dead by ICE. Minutes later, the White House Department of Homeland Security portrayed him as a terrorist. That visual contrast is the axis of the trauma.

Tweet

Minnesota was intended to be a paradigmatic case. A relatively small city, controllable by force, was chosen by the Trumpian dictatorial regime to be the victim of an operation aimed at altering the regime of citizens’ perception. What many saw as a guarantee—the possibility of filming events—is precisely what the government was seeking. Not only to normalize state violence, but to shape the way society perceives that violence. This is where the experience of the Argentine military dictatorship and its current reality under Javier Milei becomes relevant.

Minnesota was intended to be a paradigmatic case. A relatively small city, was chosen by the Trumpian dictatorial regime to be the target of an operation aimed at altering the regime of citizens’ perception. What many saw as a guarantee—the possibility of filming events—is precisely what the government was seeking.

Tweet

To understand this, it is worth returning to the concept developed by Diana Taylor of percepticide—not simply the physical elimination of bodies or rights, but the destruction of the collective capacity to see and name what is happening—which was central to the logic of state terrorism in Argentina during the seventies and forms part of the performative repertoire of modern repression. Percepticide is the operation by which terror ceases to be visible as such, even when it occurs in broad daylight, and becomes “invisible.” For Taylor, Argentines cannot see what is right in front of us.

Percepticide is the operation by which terror ceases to be visible as such, even when it occurs in broad daylight, and becomes “invisible.” For Taylor, Argentines cannot see what is right in front of us.

Tweet

A Reality TV Star Taking Lessons From an Almost Invisible Cosplayer

In the United States, however, the strategy comes from a reality-TV star who demands that nothing be hidden, not even extreme violence. The martyrdom in Minnesota becomes part of a narrative in which the federal state deploys force in a visible way, with high media impact. This does not seek to make bodies disappear in the shadows, but to model collective perception so that violence is, like the ghost in the machine, real and unreal at the same time. And, like any meme, that kind of specter is manageable and perceived as inevitable if certain rules are followed—rules that, moreover, are never articulated.

Trump does not seek to make bodies disappear in the shadows, but to model collective perception so that violence is, like the ghost in the machine, real and unreal at the same time. And, like any meme, that kind of spectre is manageable and perceived as inevitable if certain rules are followed—rules that, moreover, are never articulated.

Tweet

Minnesota, however, is a city that preserved Tocquevillian ideals, processed through the Rooseveltian experience—and I suspect also shaped by extreme climatic conditions—not to mention its repressive past marked by the murder of George Floyd. Networks of citizens who were not there for racial, sectarian, or class reasons but out of community empathy transformed the city into an involuntary mirror that makes the rest of the world see itself reflected and feel, somewhere in its psyche, a bit of envy and shame. Minnesota is the city that awakens, but also complicates the fiction of “civil order” and exposes state brutality without anesthesia.

American Hyper visibility versus Argentina Hypocrisy

That TRUMPIAN politics of brutal visibility contrasts with Argentine cultural hypocrisy. What I am saying is not moralizing, but the result of the effective “percepticidal” work carried out decades ago by the terrorist state. Terror was structured as something invisible, fragmented, bureaucratic, and deniable, and the lack of empathy oscillates bipolarly between the performance of a false communal love and the violent contempt of the neighbor. Since the Juntas, Argentina has been something comparable to Fritz Lang’s film Metropolis. Disappearances were not announced in plazas; they were hidden in legal papers, sealed official archives, inaccessible orders, “cases without those responsible,” and a state apparatus that learned to erase its own trace. In democratic times, the politics of terror is practiced from the invisibility of the apparatus, from normative opacity, information classification, the absence of accountability, and the practical denial of judicial or public visibility of the repressive process. All this while, until recently, demonstrations were tolerated and even celebrated as banal public festivity.

Since the Juntas, Argentina has been like Fritz Lang’s film Metropolis. Disappearances were hidden in a state apparatus that learned to erase its own trace. In democratic times, the politics of terror has been practiced from absence of accountability, and the denial of judicial or public visibility of the repressive process. All this while, until recently, demonstrations were even celebrated as banal public festivity.

Tweet

The decree published in the Official Gazette a couple of weeks ago by Javier Milei does not formally create a “paramilitary force” like Trump’s, but it significantly reorganizes and expands the powers of the state’s intelligence and security system, under the technical language of “prevention,” “anticipation of threats,” and “protection of the democratic order.” In concrete terms, the decree loosens the boundaries between criminal intelligence, strategic intelligence, and operational intervention, enabling agencies to collect, process, and cross-reference information on individuals, organizations, and social dynamics without necessarily requiring a clear and specific judicial order. In doing so, it blurs the line between investigation and action, between analysis and execution, and concentrates discretionary power in agencies that have historically operated with low transparency and scant effective civilian oversight. This is not an abrupt rupture of the rule of law—in a country where the Judiciary is far more porous than in the United States—but something more dangerous: an administrative normalization of the exception, where legality functions as formal cover for practices that can lead to mass surveillance, selective persecution, and, at the extreme, mechanisms of extrajudicial neutralization. In a country with a concrete history of state terrorism, this type of decree does not inaugurate the problem, but reactivates a familiar institutional architecture, where violence does not need to be shown in order to operate, because its effectiveness depends precisely on its opacity.

Milei can afford that luxury and does not need to bet as heavily as Trump on his project of institutionalized tyranny because Argentina is already “percepticidal.” Disappearance does not need scenography, because institutional invisibility is already internalized in citizens’ behavior. The decree does not impact the population’s senses because state violence—its form, its mode, its management—already operates in a regime where phone cameras, street protests, and public standards of oversight do not access the real core of power decisions. Violence does not have to be shown to exist; it is structurally embedded in what is not seen.

Violence does not have to be shown to exist; it is structurally embedded in what is not seen.

Tweet

Hence the “pseudo-Trumpian” strategy of Milei’s government does not resemble Trump’s in its mode of operation. In the United States, the strategy of visual shock seeks to impose a narrative of force: explicit violence, the presence of agents in the streets, filmed shootings, public detentions. In Argentina, terror is administered from the invisible layer of the system, through decrees, regulations, administrative apparatuses, intelligence jurisdictions that are never shown in public action. The aim is not to scandalize, but to neutralize the very possibility of critical perception. In this sense, Milei is not Trump’s student but, on the contrary, his teacher.

In Argentina, terror is administered from the invisible layer of the system, through decrees, regulations, administrative apparatuses, intelligence jurisdictions that are never shown in public action. The aim is not to scandalize, but to neutralize the very possibility of critical perception. In this sense, Milei is not Trump’s student but, on the contrary, his teacher.

Tweet

In Argentina, the perceptual challenge is internal and structural: politics and the public have learned not to see what happens behind the institutional curtain. The clash of both models—visibility versus invisibility—forces us to rethink not only what violence is exercised, but how the perception of that violence is administered.

While the world inflames its attention over what is happening in Minneapolis, in Argentina the danger is that state violence intensifies, operating in the zone of invisibility where few cameras, few trials, and few discourses penetrate. Understanding this is not an abstraction, but a step toward recovering not only memory, but the capacity to see and name what is happening now, here, and everywhere.

© Dr. Rodrigo Cañete.All rights reserved. This text may not be reproduced, distributed, translated, or quoted extensively without explicit attribution and written permission from the author.

My Book Published by Penguin Random House Can Be Found in Book Stores, Barnes&Noble, Mercado Libre and Amazon.

Deja una respuesta