Scroll Down for the English Version

El Halftime Show de Bad Bunny no desafía al poder estadounidense: le ofrece una solución estética para administrar el cuerpo latino sin redistribuir poder.

Tweet

America vs América

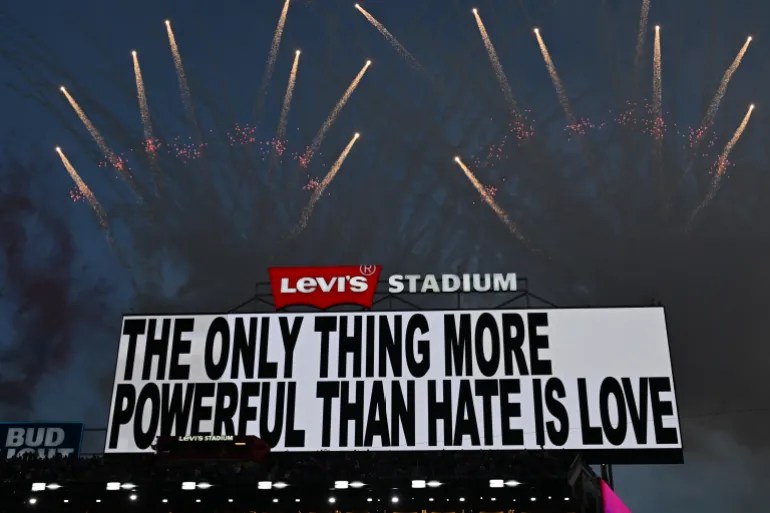

La controversia en torno a la participación de Bad Bunny en el Super Bowl Halftime Show no giró tanto en torno a la música como a algo mucho más sensible: la relación entre idioma y nación, y, en última instancia, el significado mismo del término “América” dentro y fuera de Estados Unidos. Para los grandes medios liberales estadounidenses, el hecho de que el primer halftime show mayoritariamente en español celebrara iconografías puertorriqueñas, banderas de todo el continente y cerrara con un mensaje contra el odio fue leído como un gesto de inclusión multicultural, coherente con una idea expansiva y conciliadora de lo americano. Sin embargo, las reacciones conservadoras —condensadas de forma brutal en las declaraciones de Donald Trump, que calificó el espectáculo como una afrenta a la identidad nacional porque “nadie entiende lo que dice” y porque no se canta en inglés— expusieron otra concepción: América como sinónimo exclusivo de Estados Unidos, una nación definida por una lengua, una cultura y una jerarquía claras. Esa misma fractura se replicó en redes sociales estadounidenses, donde el entusiasmo por la energía del show convivió con reacciones abiertamente hostiles al uso del español, como si el idioma funcionara todavía como frontera simbólica de pertenencia nacional. Desde Latinoamérica, en cambio, el espectáculo fue leído casi en sentido inverso: la enumeración de países, la presencia de todas las banderas americanas y la reapropiación explícita del término “América” fueron celebradas como una afirmación continental que desborda el marco estadounidense, un recordatorio de que América no es una nación sino un territorio plural. No es menor que esta disputa semántica haya reaparecido con tanta intensidad, si se recuerda que uno de los primeros gestos políticos del trumpismo fue precisamente intentar fijar, cerrar y apropiarse del significado de “America” como propiedad exclusiva, lingüística y cultural, del Estado-nación estadounidense.

Estados Unidos es un país fundado sobre un cinismo estructural que rara vez se reconoce como tal: se define a sí mismo como un melting pot mientras organiza, en la práctica, una erradicación constante del otro, tanto literal como simbólica. La diversidad es celebrada siempre que no desplace jerarquías, y la inclusión funciona más como espectáculo que como redistribución real de poder. Lo entendí con claridad hace años, desde un lugar incómodo: el de un argentino que mira a Latinoamérica desde su propia fantasía de supremacía borgeana y europeizante. Sentado a una larga mesa familiar en Los Ángeles —judíos vinculados a la NASA, clase media acomodada, trabajos de marketing farmacéutico de esos que anestesian cualquier resto de deseo— se me formularon dos preguntas reveladoras. La primera: si todo mi recorrido entre Argentina y Londres tenía como objetivo final convertirme en ciudadano norteamericano. La pregunta no era ingenua; presuponía que nadie, y menos aún un latino, puede existir sin desear secretamente ser estadounidense. La segunda: cómo alguien como yo podía tener un Rolex raro, y si no había sido, en realidad, un regalo de mi pareja. Ambas preguntas apuntaban a lo mismo: una cartografía mental donde el valor, la inteligencia, la legitimidad y la agencia están siempre en el Norte, y el Sur sólo puede existir como carencia, deseo o exceso. Esa misma cartografía organiza la idea de América como un cuerpo jerarquizado: el cerebro en el Norte; las partes bajas —ritmo, comida, sexualidad, movimiento— relegadas a Latinoamérica. Y como todo país profundamente protestante y conservador, por más liberal que se proclame, esas partes bajas deben ser cuidadosamente administradas y controladas, siempre en nombre de algún Dios, algún orden o alguna fantasía moral. El show de Bad Bunny opera exactamente dentro de esa lógica: puede mover las caderas, puede cantar en español, puede celebrar el cuerpo latino, siempre y cuando ese cuerpo no reclame autonomía plena, ni desordene la anatomía simbólica sobre la que Estados Unidos se sigue pensando a sí mismo.

En el Super Bowl, el latino puede bailar, desear y cantar en español, siempre que acepte su lugar subordinado dentro de la anatomía nacional estadounidense.

Tweet

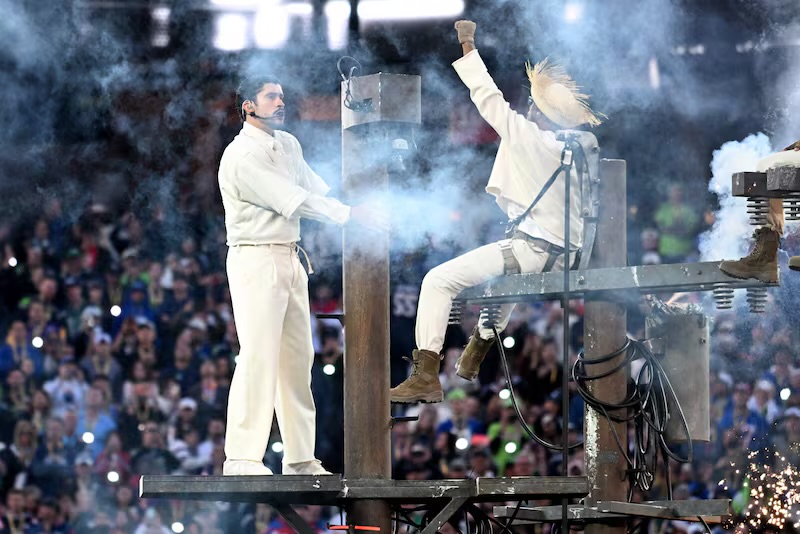

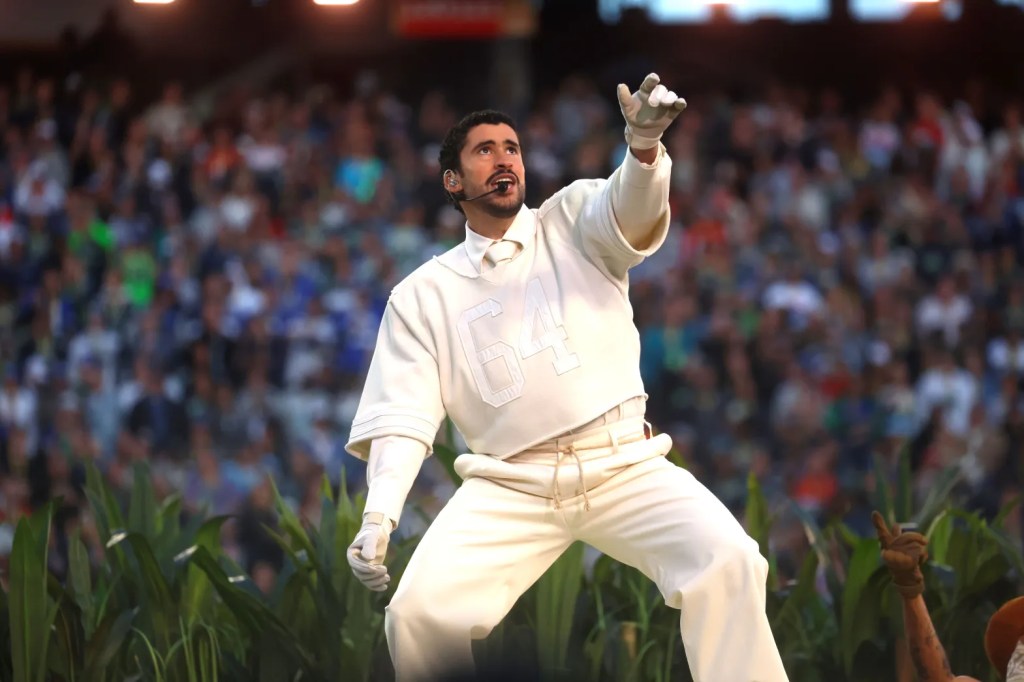

Tim Cook

El show de Bad Bunny funciona, antes que nada, como una explicitación visual del ethos liberal-demócrata estadounidense, y su lógica se vuelve evidente desde la primera imagen. Todo comienza con la manzana de Apple, un símbolo que —hasta que Tim Cook asistió sin rubor a la premiere del documental de Melania en la Casa Blanca— condensaba la fantasía de un liberalismo tecnológico progresista, ecológico y globalista. La manzana se convierte en un tubo de animación virtual idéntico a los que Apple utiliza en sus keynotes corporativos: ese pasaje pulido, abstracto, sin fricción, con el que dos veces por año se nos presenta el futuro como diseño amable. Cuando la cámara “sale” de ese tubo, la analogía es inmediata: no estamos lejos del Apple Park, del edificio circular en Palo Alto, de la escenografía de autosustentabilidad, diversidad y respeto por el planeta que hoy sabemos ficticia, sobre todo frente a la desesperación de Donald Trump por garantizarle a la Big Tech el acceso irrestricto a minerales raros a cualquier costo humano o ecológico. Pero en lugar de Tim Cook en el centro del parque, lo que aparece es el campo de juego del football americano transformado en un cañaveral. La imagen es potente porque opera en dos direcciones simultáneas: por un lado, inscribe el aporte latino desde abajo, desde el Caribe, desde el trabajo corporal y agrícola que sostiene materialmente a Estados Unidos; por el otro, reactiva —de forma cuidadosamente ambigua— la memoria del esclavismo y del trabajo precarizado que Trump, con la brutalidad asesina de ICE, volvió a poner en riesgo. Esa es la segunda gran negociación del show: el cañaveral puede leerse como denuncia simbólica, pero también como acusación silenciosa, como recordatorio de que la prosperidad americana sigue dependiendo de cuerpos racializados cuya presencia se celebra sólo cuando no reclama soberanía ni redistribución real.

Trump brutaliza el racismo; el liberalismo demócrata lo coreografía. El resultado cambia de forma, pero no de jerarquía.

Tweet

El sueño de West Side Story se acabó

El espectáculo se organiza desde el inicio como una secuencia narrativa muy precisa, marcada por el orden de las canciones. El título mismo —el nombre latino de Bad Bunny, Benito Antonio Martínez Ocasio— ya produce un eco político ineludible con Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, figura clave del liberalismo demócrata radical: una latinidad visible, integrada, mediática, aceptable. A partir de ahí, las primeras cuatro canciones funcionan como una pedagogía afectiva en acto. En Tití Me Preguntó se presenta el mercado sexual como sistema: el cortejo heterosexual organizado en torno a la acumulación, la mujer como bien intercambiable, el deseo como capital simbólico. En Yo Perreo Sola, ese mercado se desplaza hacia la autonomía femenina post-MeToo: el perreo ya no es ofrecimiento sino afirmación, pero sigue inscripto en una lógica de circulación y visibilidad. Safaera lleva ese régimen al extremo: sexualización total del cuerpo y del baile, exceso coreográfico, goce sin promesa de estabilidad. Voy a Llevarte Pa’ PR introduce el primer giro: el desplazamiento hacia lo familiar, lo territorial, lo reconocible, preparando el pasaje del deseo a la pertenencia. Esta progresión no es sólo musical sino espacial: puede seguirse literalmente en los senderos que se abren dentro del cañaveral, como si el show marcara un recorrido guiado desde el cuerpo erotizado hacia una forma aceptable de comunidad. Lo que se le ofrece al americano promedio no es la mujer pre-feminista, sino la mujer post-MeToo: sexualmente autónoma, visible, deseante, pero finalmente reinscripta en una economía afectiva regulada. El premio ya no es el amor eterno de West Side Story, sino un vínculo que sólo se sostiene mientras el carisma sexual siga funcionando. Es en ese punto donde aparece la familia, la casita humilde —humilde sólo en términos escenográficos— y el niño al que Bad Bunny entrega su Grammy, una imagen leída por los medios como una alegoría de él entregándoselo a sí mismo cuando era niño, pero cuya función simbólica es más disciplinaria que lúdica: el niño opera como anclaje moral, como cierre familiar de una narrativa que comenzó en el mercado sexual y termina en la reproducción social. El cuerpo latino puede bailar, gozar y moverse, siempre que ese movimiento desemboque, finalmente, en una forma reconocible de familia y pertenencia.

Del perreo a la familia: el show enseña cómo el cuerpo latino puede ser visible sin volverse políticamente peligroso.

Tweet

El Niño y la Latinidad Sofisticada cuando Traducida por una Rubia

Casi en paralelo a la escena del niño —una imagen que inevitablemente dialoga con el imaginario reciente de menores usados como anclaje moral en operaciones de control migratorio de Immigration and Customs Enforcement, independientemente de su literalidad— el espectáculo introduce otra escena clave: una pareja que se casa en el escenario, con Bad Bunny firmando como testigo. Para el conservadurismo estadounidense, este gesto es fundamental. La latinidad deja de ser leída únicamente como exceso sexual —la puta, el cuerpo caliente, el goce sin control— y el niño deja de ser el residuo accidental de ese exceso. En su lugar, se ofrece una doble referencia cuidadosamente negociada: por un lado, una señal anti-ICE, que humaniza al niño y lo inscribe en una narrativa de protección; por el otro, una reafirmación conservadora donde el latino aparece como hombre de familia, domesticado, matrimonial, confiable. No un peligro sexual, no un desborde, sino un sujeto que promete continuidad: llenar los campos de trabajo, engrosar el ejército, sostener la reproducción material del país. Es en ese punto donde el show deriva hacia una estética inesperada pero reveladora: una suerte de homenaje oblicuo a la Cuba prerrevolucionaria de Batista, ese burdel tropical administrado para el consumo norteamericano, con su glamour nocturno, su música elegante y su promesa de placer controlado. La entrada de Lady Gaga en Die With a Smile, acompañada por una orquesta que remite tanto al Nueva York de entreguerras como a la Habana de los años cincuenta, no es un accidente estilístico: es la sublimación final del cuerpo latino. El ritmo se vuelve melodía, el perreo se vuelve espectáculo clásico, el exceso se transforma en nostalgia elegante. La latinidad ya no amenaza: canta, sonríe, se casa y se deja orquestar. Pero…de la mano de una rubia norteamericana.

Llegados a este punto, conviene decirlo sin eufemismos: el show no interpela al poder estadounidense, le ofrece una solución estética a su problema racial. No desarma la jerarquía; la vuelve digerible. El cuerpo latino no es expulsado ni reprimido, sino administrado: primero como ritmo, luego como familia, finalmente como nostalgia elegante. Frente al trumpismo —que expone de manera obscena y brutal el racismo estructural del país— el liberalismo demócrata responde con una coreografía más sofisticada pero no menos funcional: integra al latino siempre que acepte su lugar en la anatomía nacional. Puede bailar, desear, casarse, reproducirse y emocionar, siempre que no reclame soberanía política, redistribución material ni redefinición real de lo que significa “América”. En ese sentido, el espectáculo de Bad Bunny no es una provocación sino una pedagogía: enseña cómo ser visible sin ser peligroso, cómo existir sin desordenar, cómo ser celebrado sin dejar de ser útil. Esa es su eficacia —y también su límite— dentro del imaginario demócrata contemporáneo.

Hawaii es el punto ciego del liberalismo estadounidense: la inclusión siempre llega después del despojo, cuando la soberanía ya fue convertida en estética.

Tweet

Pedagogía del Perreo Liberal

Llegados a este punto, conviene decirlo sin eufemismos, pero tampoco como conclusión: el show no interpela al poder estadounidense, le ofrece una solución estética provisoria a su problema racial. No desarma la jerarquía; la vuelve administrable. Frente al trumpismo —que expone el racismo estructural de forma burda, violenta y sin maquillaje— el liberalismo demócrata responde con una coreografía más sofisticada: integra al cuerpo latino siempre que este acepte su lugar dentro de la anatomía nacional. Puede bailar, desear, casarse, reproducirse y emocionar, siempre que no reclame soberanía política, redistribución material ni una redefinición real de lo que significa “América”. El espectáculo funciona así como una pedagogía afectiva: enseña cómo ser visible sin ser peligroso, cómo ser celebrado sin dejar de ser útil. Pero esa pedagogía tiene un punto de saturación, un momento en el que la negociación ya no puede sostenerse sólo con símbolos familiares, nostalgia musical o promesas de domesticación. Y es ahí donde el show da un paso más incómodo.

Ricky Martin y Hawaii: El momento realmente transgresor

Ese paso llega con la entrada de Ricky Martin interpretando Lo que le pasó a Hawaii. A diferencia de los momentos anteriores, acá ya no estamos ante una alegoría blanda sino ante una referencia histórica precisa. Hawái no es un símbolo abstracto: es uno de los casos más claros de colonización estadounidense por absorción y tutelaje, una anexión realizada no mediante una guerra abierta sino a través de engaños jurídicos, tratados redactados para no ser entendidos por quienes los firmaban, y una progresiva neutralización de la soberanía local bajo la promesa de protección y modernización. La historia hawaiana es la historia de cómo Estados Unidos convierte territorios en “parte de América” sin reconocerlos nunca como plenamente iguales: ni estado soberano, ni colonia formal, sino algo administrado, folklorizado y explotado. Al invocar Hawaii en ese punto del show, la latinidad deja de ser sólo cuerpo, ritmo o familia y se vuelve archivo: un recordatorio incómodo de que la inclusión americana casi siempre llega después del despojo, y que el tutelaje liberal —amable, legalista, civilizatorio— puede ser tan eficaz como la violencia abierta. Es ahí donde el espectáculo roza su propio límite: donde la celebración se vuelve memoria, y la memoria amenaza con romper la coreografía.

Hawaii es el punto ciego del liberalismo demócrata porque demuestra que la violencia fundacional no siempre adopta la forma del garrote, la cárcel o el muro. A veces se ejerce mediante tutela, lenguaje jurídico, promesas de protección y una administración paciente del deseo. La anexión hawaiana no fue una explosión de brutalidad trumpista sino una operación prolija: tratados redactados para no ser comprendidos, soberanía diluida en nombre del progreso, cultura convertida en paisaje y folklore para consumo externo. Por eso la aparición de Ricky Martin cantando Lo que le pasó a Hawai no es un momento más del show, sino su límite interno. Ahí la negociación liberal ya no alcanza, porque lo que se pone en juego no es la visibilidad del cuerpo latino sino la memoria de cómo Estados Unidos produce “América”: absorbiendo territorios, administrando poblaciones y celebrando la diferencia sólo después de neutralizarla políticamente. Hawaii recuerda que la inclusión casi siempre llega tarde, cuando la soberanía ya fue vaciada y el conflicto transformado en estética. Y en ese sentido, el Halftime Show no contradice esa historia: la confirma. Canta en español, enumera países, promete amor frente al odio, pero lo hace dentro de un marco donde “América” sigue siendo un nombre que se concede desde el Norte y se acepta desde abajo. Lo verdaderamente inquietante del espectáculo no es lo que dice, sino lo que demuestra: que el liberalismo estadounidense puede integrar casi todo —el ritmo, el cuerpo, la familia, incluso la memoria— siempre que esa integración no cuestione el derecho último a tutelar, absorber y redefinir qué significa pertenecer.

At the Super Bowl Halftime Show, Bad Bunny integrates Latinos only on the condition that they accept their place (of inferiority) within the brutal national anatomy (both Democratic and Trumpian). (ENG)

Bad Bunny’s Halftime Show doesn’t challenge U.S. power; it offers an aesthetic solution to manage the Latino body without redistributing power.

Tweet

América vs America

The controversy surrounding Bad Bunny’s participation in the Super Bowl Halftime Show revolved less around music than around something far more sensitive: the relationship between language and nation, and ultimately the very meaning of the term “America” inside and outside the United States. For mainstream liberal U.S. media, the fact that the first halftime show performed largely in Spanish celebrated Puerto Rican iconography, displayed flags from across the continent, and closed with an anti-hate message was read as a gesture of multicultural inclusion, consistent with an expansive and conciliatory idea of what “America” is supposed to be. Conservative reactions, however—brutally condensed in Donald Trump’s statements, dismissing the show as an affront to national identity because “nobody understands what he’s saying” and because it was not sung in English—revealed a very different conception: America as an exclusive synonym for the United States, a nation defined by a single language, a unified culture, and a clear hierarchy. The same fracture appeared across U.S. social media, where enthusiasm for the show’s energy coexisted with openly hostile reactions to the use of Spanish, as if language were still functioning as a symbolic border of national belonging. From Latin America, by contrast, the spectacle was read almost in reverse: the enumeration of countries, the presence of all American flags, and the explicit reappropriation of the term “America” were celebrated as a continental affirmation that exceeds the U.S. framework, a reminder that America is not a nation but a plural territory. It is no small detail that this semantic dispute reemerged so forcefully, considering that one of the very first political gestures of Trumpism was precisely an attempt to fix, close off, and appropriate the meaning of “America” as the exclusive linguistic and cultural property of the U.S. nation-state.

At the Super Bowl, Latinos are allowed to dance, desire, and sing in Spanish—so long as they accept their subordinate place within America’s national anatomy.

Tweet

The United States is a country founded on a form of structural cynicism that it rarely acknowledges as such: it defines itself as a melting pot while, in practice, organizing the constant eradication of the other, both literally and symbolically. Diversity is celebrated only insofar as it does not displace hierarchies, and inclusion operates more as spectacle than as any real redistribution of power. I understood this with particular clarity years ago, from an uncomfortable position: that of an Argentine who looks at Latin America through his own Borges-inflected, Europeanizing fantasy of supremacy. Sitting at a long family table in Los Angeles—Jewish relatives connected to NASA, a relatively comfortable middle class, pharmaceutical marketing jobs of the kind that anesthetize whatever remains of desire—I was asked two revealing questions. The first was whether my entire peripatetic trajectory between Argentina and London was ultimately aimed at becoming an American citizen. The question was not naïve; it assumed that no one, and especially no Latino, could exist without secretly desiring to be American. The second concerned my watch: how someone like me could own such a rare Rolex, and whether it had not, in fact, been a gift from my partner. Both questions pointed to the same mental cartography: one in which value, intelligence, legitimacy, and agency are always located in the North, while the South can only exist as lack, desire, or excess. That same cartography organizes the idea of America as a hierarchized body: the brain in the North; the lower parts—rhythm, food, sexuality, movement—relegated to Latin America. And like any deeply Protestant and conservative country, no matter how liberal it claims to be, those lower parts must be carefully administered and controlled, always in the name of some God, some order, or some moral fantasy. Bad Bunny’s show operates squarely within this logic: hips may move, Spanish may be sung, the Latino body may be celebrated—so long as that body does not claim full autonomy or disrupt the symbolic anatomy through which the United States continues to imagine itself.

Trump brutalizes racism; Democratic liberalism choreographs it. The form changes, the hierarchy does not.

Tweet

Tim Cook

Bad Bunny’s show functions, above all, as a visual articulation of the U.S. liberal-democratic ethos, and this becomes evident from its very first image. Everything begins with the Apple logo—a symbol that, until Tim Cook unapologetically attended the premiere of Melania’s documentary at the White House, condensed the fantasy of a progressive, ecological, globalist technological liberalism. The apple morphs into a virtual animation tube identical to those Apple uses in its corporate keynotes: that polished, abstract, frictionless passage through which the future is presented twice a year as friendly design. When the camera “emerges” from that tube, the analogy is unmistakable: we are not far from Apple Park, from the circular building in Palo Alto that stages sustainability, diversity, and respect for the planet—an illusion we now know to be fictitious, especially in light of Donald Trump’s desperation to secure unrestricted access to rare minerals for Big Tech at any human or ecological cost. Yet instead of Tim Cook standing at the center of the park, what appears is the American football field transformed into a sugarcane plantation. The image is powerful because it operates in two directions at once: on the one hand, it inscribes the Latino contribution from below, from the Caribbean, from the bodily and agricultural labor that materially sustains the United States; on the other, it reactivates—through a carefully ambiguous gesture—the memory of slavery and precarious labor that Trump, through the murderous brutality of ICE, has once again placed at risk. This is the second major negotiation of the show: the sugarcane field can be read as symbolic denunciation, but also as a silent accusation, a reminder that American prosperity still depends on racialized bodies whose presence is celebrated only when they do not demand sovereignty or real redistribution.

The Official Ending of West Side Story’s Humanism

From the outset, the spectacle is organized as a highly precise narrative sequence, structured by the order of the songs. The title itself—the Latino name of Bad Bunny, Benito Antonio Martínez Ocasio—produces an unavoidable political echo with Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, a key figure of radical Democratic liberalism: a visible, integrated, media-friendly, acceptable Latinidad. From there, the first four songs function as an affective pedagogy in action. Tití Me Preguntó presents the sexual market as a system: heterosexual courtship organized around accumulation, women as interchangeable goods, desire as symbolic capital. In Yo Perreo Sola, that market shifts toward post–MeToo female autonomy: perreo is no longer an offer but an assertion, yet it remains inscribed within a logic of circulation and visibility. Safaera pushes this regime to its extreme: total sexualization of the body and dance, choreographic excess, pleasure without any promise of stability. Voy a Llevarte Pa’ PR introduces the first turn: a movement toward the familiar, the territorial, the recognizable, preparing the passage from desire to belonging. This progression is not only musical but spatial: it can literally be traced along the paths opening through the sugarcane field, as if the show were guiding the viewer from the eroticized body toward an acceptable form of community. What is offered to the average American is not the pre-feminist woman, but the post–MeToo woman: sexually autonomous, visible, desiring, yet ultimately reinscribed within a regulated affective economy. The prize is no longer the eternal love of West Side Story, but a bond that survives only as long as sexual charisma continues to function. It is at this point that the family appears, the humble house—humble only in scenic terms—and the child to whom Bad Bunny hands his Grammy, an image read by the media as an allegory of him giving it to his younger self, but whose symbolic function is more disciplinary than playful: the child operates as a moral anchor, the familial closure of a narrative that began in the sexual market and ends in social reproduction. The Latino body may dance, enjoy, and move, provided that such movement ultimately leads to a recognizable form of family and belonging.

Trump brutalizes racism; Democratic liberalism choreographs it. The form changes, the hierarchy does not.

Tweet

Latin Sophistication Only If Sang by a Blonde New Yorker

Almost in parallel with the scene involving the child—an image that inevitably resonates with the recent imaginary of minors used as moral leverage in immigration control operations by Immigration and Customs Enforcement, regardless of literal intent—the spectacle introduces another key scene: a couple getting married onstage, with Bad Bunny signing as witness. For American conservatism, this gesture is fundamental. Latinidad ceases to be read solely as sexual excess—the prostitute, the overheated body, pleasure without control—and the child ceases to be the accidental residue of that excess. In its place, a carefully negotiated double reference is offered: on the one hand, an anti-ICE signal that humanizes the child and inscribes them within a narrative of protection; on the other, a conservative reaffirmation in which the Latino appears as a domesticated, marital, reliable family man. Not a sexual threat, not an overflow, but a subject who promises continuity: to fill the labor fields, to swell the ranks of the military, to sustain the material reproduction of the nation. It is at this point that the show shifts toward an unexpected yet revealing aesthetic: a kind of oblique homage to pre-revolutionary Batista-era Cuba, that tropical brothel administered for North American consumption, with its nocturnal glamour, elegant music, and promise of controlled pleasure. Lady Gaga’s entrance in Die With a Smile, accompanied by an orchestra evoking both interwar New York and 1950s Havana, is no stylistic accident: it is the final sublimation of the Latino body. Rhythm becomes melody, perreo becomes classical spectacle, excess turns into elegant nostalgia. Latinidad no longer threatens: it sings, smiles, marries, and allows itself to be orchestrated—hand in hand with a blonde North American woman.

At this point, it must be said without euphemism: the show does not challenge U.S. power; it offers an aesthetic solution to its racial problem. It does not dismantle hierarchy; it renders it digestible. The Latino body is neither expelled nor repressed, but administered—first as rhythm, then as family, finally as elegant nostalgia. In contrast to Trumpism—which exposes the country’s structural racism in an obscene, brutal, unvarnished way—Democratic liberalism responds with a more sophisticated but no less functional choreography: it integrates the Latino subject only insofar as they accept their place within the national anatomy. They may dance, desire, marry, reproduce, and move emotionally, provided they do not claim political sovereignty, material redistribution, or a genuine redefinition of what “America” means. In that sense, Bad Bunny’s spectacle is not a provocation but a pedagogy: it teaches how to be visible without being dangerous, how to exist without disrupting, how to be celebrated without ceasing to be useful. That is its effectiveness—and also its limit—within the contemporary Democratic imaginary.

Hawai‘i is the blind spot of U.S. liberalism: inclusion arrives only after dispossession, once sovereignty has already been aestheticized.

Tweet

And yet, this is not the conclusion. The show’s pedagogy reaches a point of saturation, a moment when negotiation can no longer be sustained solely through familial symbols, musical nostalgia, or promises of domestication. That moment arrives with Ricky Martin’s entrance, performing Lo que le pasó a Hawai.

Ricky Martin and Hawaii: The Radical Moment

Unlike previous moments, this is no soft allegory but a precise historical reference. Hawai‘i is not an abstract symbol: it is one of the clearest cases of U.S. colonization through absorption and tutelage, an annexation achieved not through open warfare but via legal deception, treaties drafted to be unintelligible to those who signed them, and the gradual neutralization of sovereignty under the promise of protection and modernization. Hawaiian history is the history of how the United States turns territories into “part of America” without ever recognizing them as fully equal: neither sovereign state nor formal colony, but something administered, folklorized, and exploited. By invoking Hawai‘i at this point in the show, Latinidad ceases to be merely body, rhythm, or family and becomes archive: an uncomfortable reminder that American inclusion almost always arrives after dispossession, and that liberal tutelage—polite, legalistic, civilizational—can be just as effective as overt violence. It is here that the spectacle brushes against its own limit: where celebration turns into memory, and memory threatens to fracture the choreography.

Hawai‘i is the blind spot of Democratic liberalism because it shows that foundational violence does not always take the form of batons, prisons, or walls. Sometimes it is exercised through tutelage, legal language, promises of protection, and the patient administration of desire. Hawaiian annexation was not a Trumpian eruption of brutality but a meticulous operation: treaties designed not to be understood, sovereignty diluted in the name of progress, culture converted into landscape and folklore for external consumption. That is why Ricky Martin singing Lo que le pasó a Hawai is not just another moment in the show but its internal limit. Here, liberal negotiation is no longer enough, because what is at stake is not the visibility of the Latino body but the memory of how the United States produces “America”: by absorbing territories, administering populations, and celebrating difference only after neutralizing it politically. Hawai‘i reminds us that inclusion almost always comes too late, once sovereignty has already been emptied and conflict transformed into aesthetics. In this sense, the Halftime Show does not contradict that history—it confirms it. It sings in Spanish, enumerates countries, promises love over hate, but does so within a framework in which “America” remains a name granted from the North and accepted from below. What is truly unsettling about the spectacle is not what it says, but what it demonstrates: that U.S. liberalism can integrate almost everything—rhythm, body, family, even memory—so long as that integration does not challenge its ultimate right to tutor, absorb, and redefine what it means to belong.

Deja una respuesta