Scroll Down for the English Version

La Mala Educación de esta semana

La flexibilización laboral no es “modernización”: es la pieza local de un experimento global de post-neoliberalismo cruel. Se desmontan derechos y amortiguadores sociales para ofrecer “seguridad jurídica” al capital extractivo y financiero en un mundo fracturado. Argentina no reforma: se alinea.

Tweet

La flexibilización laboral y el experimento global del post-neoliberalismo cruel

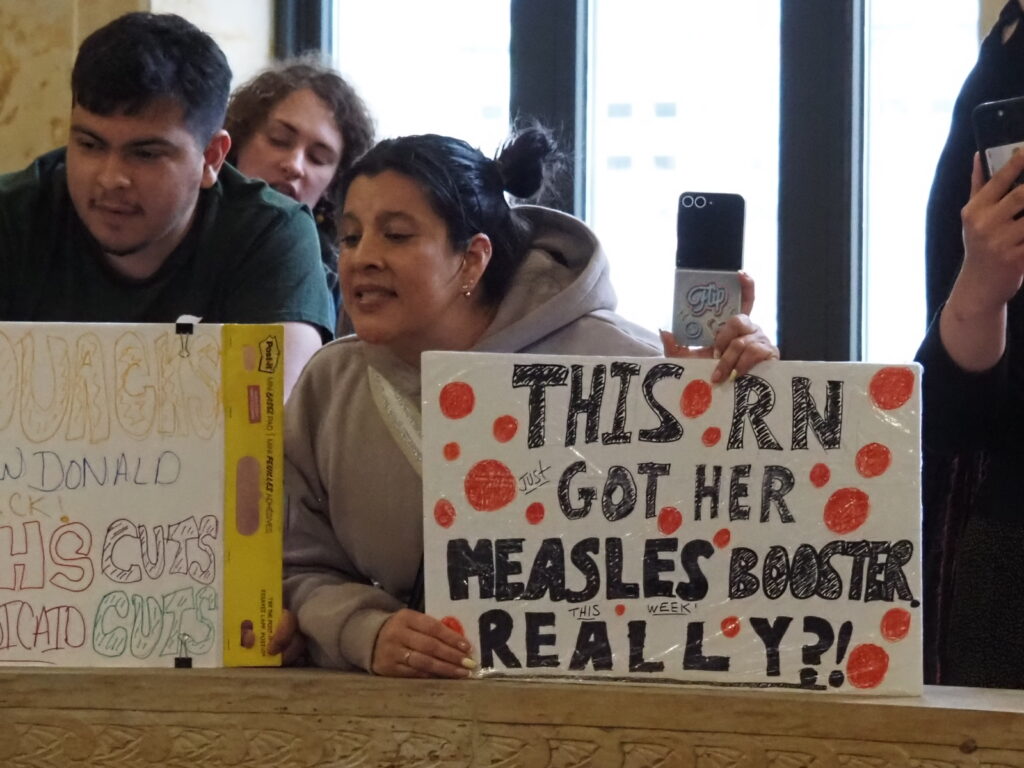

La imagen es obscena en su literalidad. Mientras en el Congreso argentino se debatía y finalmente se aprobaba la ley de flexibilización laboral, y mientras sindicatos y organizaciones denunciaban represión en las calles, Javier Milei aparecía cantando y celebrando al lado de Viktor Orbán —primer ministro de Hungría y laboratorio europeo de la “democracia iliberal”— y, también, de Gianni Infantino —presidente de la FIFA y operador central del negocio político-financiero del fútbol global. Esto ocurría en un escenario que Donald Trump pretendía convertir en un simulacro de Naciones Unidas: su Board of Peace, una “ONU paralela” donde la membresía permanente se compra con mil millones de dólares y el portero es el propio Trump. Pero el dato decisivo no es que Milei se riera: es que el anfitrión estaba en estado de decadencia evidente. El anfitri dejó delegaciones esperando mientras escuchaba su playlist con earphones, entró tarde, se puso a improvisar como si estuviera desorientado, anunció partidas de miles de millones que constitucionalmente no puede aprobar y convirtió la supuesta cumbre en un espectáculo personalista, errático y senil, el tipo de escena que debería encender alarmas en cualquier país que se presente como su aliado preferente.

Ese “papelón” no es un chisme. Es el resumen de una mutación: Estados Unidos ya no ofrece un orden multilateral (ONU, OMS, reglas compartidas) sino un modelo de soberanía tercerizada, donde el alineamiento se compra, la disciplina se exige y el control institucional se reemplaza por lealtades personales y negocios. Cuando Milei canta en ese escenario en el mismo momento en que Argentina flexibiliza el trabajo, lo que se ve no es folclore presidencial: se ve a un país aceptando entrar como experimento en, lo que podríamos denominar, el post-neoliberalismo cruel. Un sistema diseñado para romper amortiguadores sociales internos mientras el centro imperial se descompone y busca reemplazar la legalidad por “clubes” privados de poder.

La teoría del unitary executive, los signing statements, Guantánamo y el fallo Trump v. United States (2024) no son episodios aislados: son la consolidación de un Presidente blindado frente al Congreso. Cuando el Ejecutivo redefine sus límites, el Parlamento se vuelve decorativo. Y ese modelo irradia.

Tweet

Ese foro —concebido explícitamente como alternativa a la ONU— celebró su primera reunión en Washington en el edificio del antiguo U.S. Institute of Peace, rebautizado informalmente como “Donald J. Trump Institute of Peace”. El esquema organizativo establece que la membresía permanente requiere un aporte de mil millones de dólares y que Donald Trump concentra la potestad de admitir miembros, definir representación y administrar los fondos. Hasta el momento no hay evidencia pública de que ningún país haya desembolsado esa suma. Es una pregunta legítima —y políticamente explosiva— si Argentina comprometió o comprometerá recursos en ese esquema; hasta ahora, no hay confirmación de que nadie haya pagado.

Veintisiete países han manifestado interés en participar, pero la arquitectura revela más debilidad que fortaleza. La negativa fue explícita y coordinada por parte de Austria, Francia, Alemania, Grecia, Irlanda, Italia, Nueva Zelanda, Noruega, Polonia, Eslovenia, Suecia, el Reino Unido, Ucrania y el Vaticano. Que el Reino Unido y el Vaticano estén en esa lista no es un detalle diplomático menor: implica el rechazo tanto de una potencia nuclear histórica aliada de Washington como de “la” autoridad moral global con capacidad de influencia transversal. Pero… ¿Por qué el bloque no es hegemónico? La respuesta es simple….porque no incluye a las economías centrales de la Unión Europea ni a los socios estratégicos tradicionales de Estados Unidos en el G7. No concentra poder financiero real ni legitimidad institucional internacional. Lo que sí reúne es otra cosa: gobiernos con perfiles autoritarios en consolidación (como Hungría, Bielorrusia o Argentina), administraciones bajo acusaciones de retrocesos democráticos, o países cuya supervivencia económica depende críticamente del acceso al mercado estadounidense. Es un club de alineamiento, no un orden internacional. Además, el mapa geopolítico no es casual. Varios de los interesados ocupan posiciones estratégicas en la contención o rodeo indirecto de Rusia y China, o dependen de la protección estadounidense en conflictos regionales. No es un bloque multilateral universalista; es una red selectiva de lealtades dentro de un tablero de competencia entre potencias. En otras palabras: no estamos frente a una nueva ONU. Estamos frente a un intento de rediseñar la gobernanza internacional como una federación de dependencias.

Ahí estaba Milei, celebrando.

Epstein no es solo escándalo sexual: es inteligencia cruda + finanzas. Archivos incompletos, posible chantaje, redes entre política, academia, banca y Wall Street. Si el dinero compra poder global, la pregunta es bancaria: ¿por dónde circuló, quién lo habilitó y quién lo está tapando hoy?

Tweet

La Implosion de la Elite Politica (y Empresarial) Argentina como Dirigencia

En Argentina, la conversación pública quedó atrapada en la superficie de la sanción de la ley de flexibilización laboral: quién dio quórum, qué gobernadores peronistas facilitaron la votación, qué diputados miraban al piso mientras se aprobaba la norma. Esa es la escena que domina la televisión y las redes. Pero justamente el propósito de este blog es salir de esa telenovela parlamentaria (El Destape, por ejemplo) y mirar el proceso desde un ángulo estructural. Preguntarse qué gobernador “traicionó” es, en el fondo, una pregunta retórica. Nadie vota una reforma de este calibre por distracción; se vota por interés, por cálculo o por alineamiento estratégico. El verdadero problema no es quién traicionó, sino qué sistema de poder hace racional esa traición.

La ley de flexibilización laboral no es simplemente una reforma técnica del mercado de trabajo. Es una pieza dentro de un rediseño más amplio. No es el neoliberalismo clásico de los años noventa, que prometía modernización, apertura y crecimiento bajo reglas globales relativamente estables. Es algo más áspero: una fase en la que los amortiguadores sociales —protección laboral, negociación colectiva, presunción de relación de dependencia— son desmontados para ofrecer a los capitales internacionales una plataforma de bajo costo en un mundo feroz. No se trata solo de reducir “costos laborales”; se trata de convertir a los países periféricos en zonas de prueba donde se ensayan marcos jurídicos cada vez más favorables al capital financiero y extractivo. En ese sentido, Argentina no está simplemente “haciendo una reforma”. Está enviando una señal de integración a un bloque internacional que combina concentración ejecutiva, debilitamiento institucional y reconfiguración del orden multilateral. La flexibilización laboral es el gesto doméstico de un alineamiento externo.

Corea del Sur condena a su ex presidente por un autogolpe; Brasil procesa a Bolsonaro. En EE.UU., Trump queda blindado por inmunidad y captura institucional. Esa asimetría define la época: algunas democracias todavía sancionan, otras normalizan al emperador—y la periferia paga el costo.

Tweet

Los primeros artículos alteran la presunción de relación laboral y amplían el uso de figuras como el monotributo, debilitando el reconocimiento automático del vínculo empleador-empleado. El argumento oficial fue la informalidad estructural, especialmente entre jóvenes que nunca conocieron un empleo formal. Pero el efecto sistémico es otro: abaratar el trabajo, flexibilizar despidos, reducir litigiosidad y ofrecer “seguridad jurídica” a capitales internacionales en un contexto de competencia feroz por inversiones extractivas —litio, energía, minería. El mensaje hacia el exterior es claro: Argentina está dispuesta a ajustar su legislación social para integrarse a un bloque que privilegia disciplina fiscal, apertura extractiva y subordinación.

Cuando hablo de post-neoliberalismo cruel no me refiero a un slogan. Me refiero a una mutación concreta del capitalismo global posterior a 2008 y acelerada tras la pandemia y la guerra en Ucrania. El neoliberalismo clásico de los noventa funcionaba dentro de un orden relativamente estable: Organización Mundial del Comercio, acuerdos multilaterales, cadenas globales de valor extendidas, hegemonía financiera norteamericana sin competencia estratégica abierta. La promesa —verdadera o falsa— era que la apertura traería crecimiento. Hoy ese orden está fracturado. La rivalidad entre Estados Unidos y China atraviesa comercio, tecnología, energía y finanzas. La guerra en Ucrania reconfiguró flujos energéticos. El Indo-Pacífico es zona de tensión permanente. En ese contexto, los países periféricos ya no son simplemente “mercados emergentes”: son plataformas estratégicas. El litio argentino no es solo un commodity; es un insumo crítico para baterías, transición energética y autonomía industrial. Las reservas de Vaca Muerta no son solo hidrocarburos; son piezas en la seguridad energética occidental. El post-neoliberalismo cruel opera en este tablero. No promete bienestar general; promete estabilidad macro y previsibilidad jurídica para capitales en un mundo volátil. Para lograrlo, reduce derechos laborales, debilita negociación colectiva, flexibiliza despidos y limita litigiosidad. No porque crea en el “derrame”, sino porque compite por atraer inversión frente a otras jurisdicciones igualmente precarizadas.

Milei cantando con Orbán en la “ONU paralela” de Trump no fue folklore: fue alineamiento. Argentina entra como laboratorio periférico de un bloque autoritario y extractivista que compra lealtades, exige disciplina y reemplaza reglas por negocios. Si el centro se fractura, el virrey hereda el vacío.

Tweet

En este esquema, la deuda externa cumple un rol disciplinador. Argentina negocia permanentemente con el FMI, emite bonos en mercados internacionales y nacionales y depende del crédito de grandes bancos globales. JPMorgan Chase no es un actor decorativo: es uno de los estructuradores y colocadores clave de deuda soberana en mercados emergentes. Cuando el Ministerio de Economía argentino conversa con grandes bancos de inversión y el mismisimo ministro viene de ese banco, no está simplemente buscando financiamiento; está negociando condiciones de inserción en un sistema promiscuo. Y ese sistema está atravesado por las mismas redes que aparecen en el caso Jeffrey Epstein: flujos bancarios, información privilegiada, vínculos entre elites políticas, académicas y empresariales. El capital financiero no opera en el vacío moral; opera en redes de poder.

Por eso la flexibilización laboral no puede leerse solo como “modernización”. Es la adecuación del marco jurídico argentino a una competencia sistémica donde los países periféricos ofrecen mano de obra flexible, estabilidad fiscal y seguridad jurídica a cambio de acceso a capital. En un mundo donde el centro —Estados Unidos bajo Donald Trump— intenta reconfigurar o incluso reemplazar el orden multilateral, la periferia se vuelve laboratorio. Lo cruel no es solo el contenido de la reforma. Es el contexto: se desmantelan protecciones en nombre de una estabilidad cuya cabeza institucional muestra signos de descomposición, personalismo y captura financiera.

El Presidente Monarca y la Verdadera Realeza Presa

Para entender el sentido de esa señal hay que mirar a Washington, pero no solo al de hoy, sino al de las últimas cuatro décadas. Desde la década de 1980, sectores del Partido Republicano comenzaron a desarrollar con mayor sistematicidad la teoría del unitary executive: la idea de que el presidente, como jefe del Poder Ejecutivo, concentra en sí mismo toda la autoridad ejecutiva y no puede ser efectivamente limitado por el Congreso ni por agencias administrativas independientes. No es una metáfora. Es una doctrina jurídica que busca reconfigurar el equilibrio de poderes.

Durante la presidencia de Ronald Reagan, esa teoría empezó a adquirir forma institucional. Su fiscal general, Edwin Meese —un abogado conservador clave en la reorientación ideológica del Departamento de Justicia— impulsó la idea de fortalecer al presidente frente al Congreso incluso cuando las encuestas mostraban que la opinión pública no acompañaba determinadas políticas. El objetivo explícito era garantizar continuidad ejecutiva aun si el electorado desaprobaba. Uno de los instrumentos que emergió en ese contexto fueron los signing statements —declaraciones interpretativas al firmar una ley— mediante las cuales el presidente sanciona formalmente una norma aprobada por el Congreso pero simultáneamente declara cómo la interpretará o qué partes considera no vinculantes. Traducido sin tecnicismos: el presidente firma la ley, pero anuncia que la aplicará según su propio criterio constitucional. La herramienta no nació con Reagan, pero bajo su administración y las posteriores se convirtió en arma política.

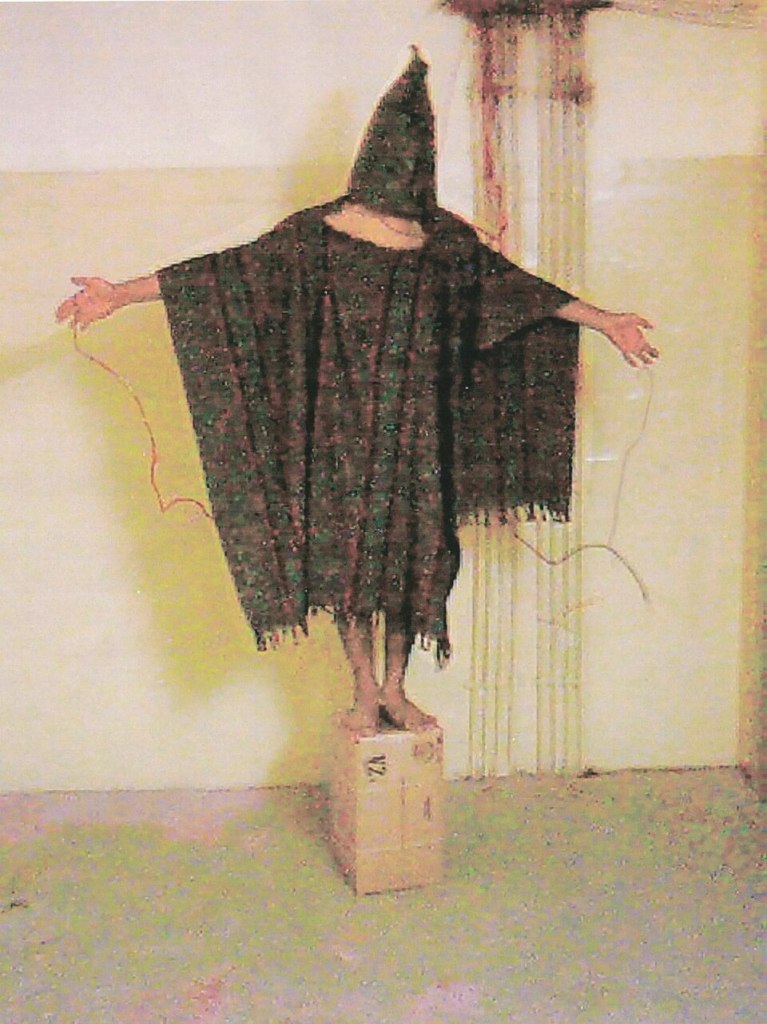

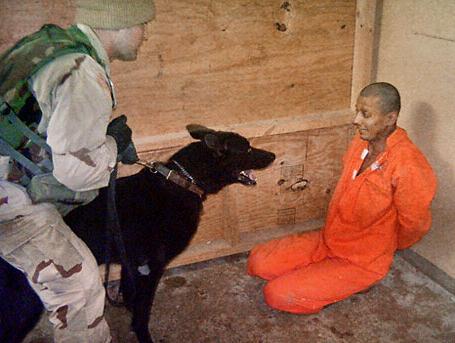

Esa práctica alcanzó su momento de máxima tensión durante la presidencia de George W. Bush. Tras los atentados del 11 de septiembre de 2001, el Ejecutivo expandió drásticamente sus poderes en nombre de la seguridad nacional y esto llevo a que en el 2004 estallara el escándalo de torturas en la prisión de Abu Ghraib. El senador republicano John McCain, veterano de Vietnam y víctima de tortura, impulsó una enmienda que prohibía expresamente tratos crueles e inhumanos a detenidos bajo custodia estadounidense. El Congreso aprobó esa prohibición. Pero Bush firmó la ley acompañándola con un signing statement que afirmaba que el presidente conservaría autoridad para interpretarla a la luz de sus poderes como comandante en jefe. En términos prácticos, el Ejecutivo se reservaba margen para continuar prácticas que el Congreso buscaba restringir. Guantánamo —el centro de detención en la base naval estadounidense en Cuba— se convirtió en el símbolo de esa expansión ejecutiva: detenciones indefinidas, tribunales militares especiales, uso de técnicas de interrogatorio que organismos internacionales calificaron como tortura.

En paralelo, figuras jurídicas como Samuel Alito —entonces funcionario del Departamento de Justicia y hoy juez de la Corte Suprema norteamericana— contribuyeron a la argumentación teórica que justificaba ampliar el poder presidencial frente al Legislativo. Lo que en los años ochenta parecía una doctrina marginal comenzó a instalarse como corriente hegemonica conservadora. Hubo fallos judiciales que limitaron al Ejecutivo. Pero la tendencia de fondo fue clara: expansión del margen presidencial en materia de seguridad nacional y política exterior, reducción práctica de controles efectivos y normalización del argumento de que el presidente puede reinterpretar la voluntad legislativa. El Presidente del sistema presidencialista se convertia en una suerte de monarca. Cuando hoy se observa el comportamiento de Donald Trump —sus anuncios unilaterales de miles de millones de dólares sin aprobación legislativa, su apelación constante a la seguridad nacional para justificar decisiones disruptivas— no estamos ante un exabrupto aislado. Estamos ante la culminación de una trayectoria doctrinaria que comenzó hace cuarenta años.

En julio de 2024, la Supreme Court of the United States resolvió el caso Donald Trump v. United States, y el alcance del fallo fue mucho más profundo de lo que los medios reflejaron. La Corte sostuvo que el presidente goza de inmunidad penal absoluta por actos realizados dentro del núcleo de sus funciones oficiales y de inmunidad presunta —es decir, difícilmente refutable— respecto de otros actos vinculados al ejercicio del cargo. Traducido al lenguaje político: si el presidente actúa en el marco de sus “atribuciones oficiales”, no puede ser procesado penalmente por ello. El problema está en la definición de “atribución oficial”. ¿Quién decide qué entra en esa categoría? La propia Corte Suprema. Es decir, el tribunal no solo amplía el margen del Ejecutivo sino que se reserva la potestad de determinar cuándo ese margen aplica. En paralelo, existe en el Departamento de Justicia un memo —no una ley votada por el Congreso— que sostiene que un presidente en funciones no debe ser procesado penalmente mientras ejerce el cargo. El resultado es un Presidente blindado: un monarca absoluto no hereditario.

¿Dónde queda el Congreso en este esquema? Formalmente, conserva la potestad de legislar, de asignar presupuesto y de iniciar juicios políticos. Pero en la práctica, si el Ejecutivo puede reinterpretar leyes mediante signing statements, invocar seguridad nacional para ampliar competencias y contar con una Corte que le reconoce inmunidad ampliada, el Parlamento queda reducido a un actor condicionado. Puede aprobar normas, pero el Ejecutivo puede reinterpretarlas; puede asignar fondos, pero el presidente puede anunciar compromisos internacionales bajo la lógica de política exterior y luego forzar la negociación. El paralelismo con Argentina es inquietante. Cuando el Ejecutivo acumula herramientas para gobernar por decreto, redefine la presunción de relación laboral, impulsa reformas en bloque y proyecta eventualmente alteraciones constitucionales, el Legislativo queda en posición reactiva. La pregunta no es si el Congreso existe; la pregunta es cuánta capacidad real tiene para frenar un calibramiento del sistema en su totalidad.

El Presidente/Monarca blindado es el suelo sobre el que se construye el siguiente movimiento: la creación de estructuras paralelas bajo control directo del Ejecutivo. Trump no solo promovió la salida de la World Health Organization; impulsó la creación de una versión estadounidense bajo la órbita del Departamento de Salud encabezado por Robert F. Kennedy Jr.. Kennedy no es un funcionario técnico tradicional: es un dirigente con historial de confrontación con agencias sanitarias, promotor de posiciones controversiales en materia de vacunas y regulaciones médicas, y figura mediática con vínculos transversales en la política norteamericana. El proyecto implica gastar aproximadamente 2.000 millones de dólares anuales para replicar funciones que Estados Unidos ya financiaba en el marco multilateral con un aporte cercano a los 680 millones. No se trata de eficiencia económica; se trata de control político. Salir del organismo multilateral —donde existen reglas, supervisión internacional y cooperación entre estados— para recrearlo bajo jurisdicción doméstica significa concentrar decisiones sanitarias globales bajo mando nacional y, en última instancia, presidencial/monárquico.

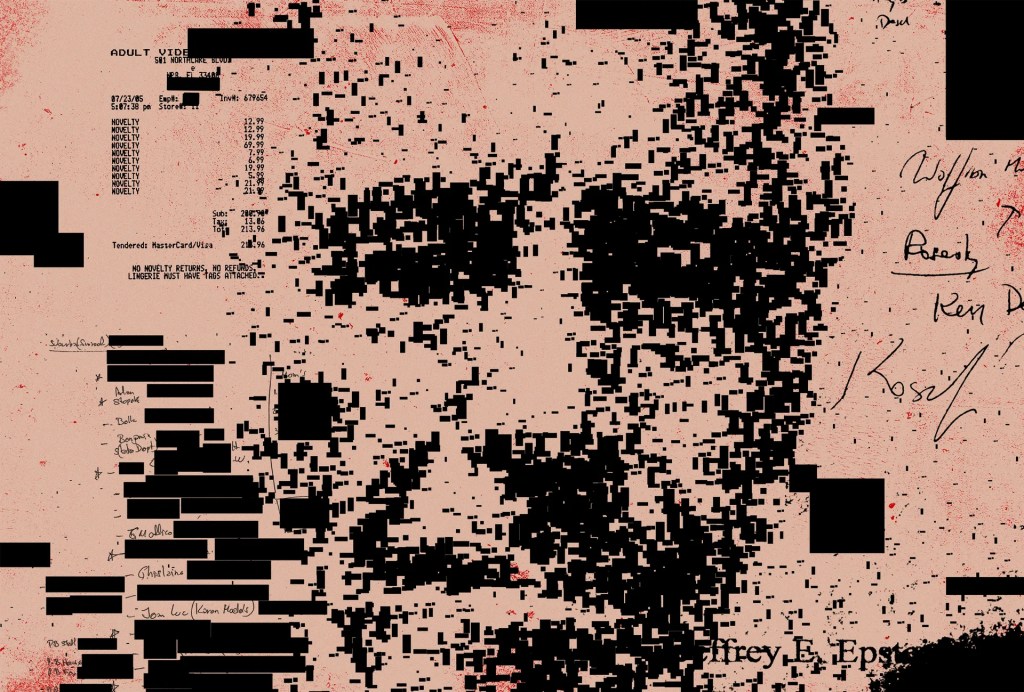

En este entramado aparece otro nombre que conecta con el subsuelo financiero del poder: Mehmet Oz (a cargo de Medicaid), conocido como Dr. Oz, figura pública que incursionó en política y cuyo nombre aparece mencionado en los archivos vinculados a Jeffrey Epstein. Del mismo modo, JPMorgan Chase mantuvo relación bancaria con Epstein durante años y fue objeto de demandas por su rol en la facilitación de cuentas y transferencias. En los propios archivos judiciales, cuando se le preguntó a Epstein por su vínculo con John Mack —ex CEO de Morgan Stanley y figura central de Wall Street—, Epstein invocó la Quinta Enmienda de la Constitución estadounidense, que protege contra la autoincriminación. Es decir, se negó a responder. La moneda de ese circuito no era solamente el dinero; era la información. Información financiera, información política, información sensible.

El patrón es coherente: concentración de poder ejecutivo, debilitamiento de controles legislativos, creación de estructuras paralelas bajo control presidencial y circulación de redes financieras donde bancos globales y elites políticas interactúan. No es ahorro. No es eficiencia. Es recentralización y control en un contexto de competencia sistémica global.

La Otra Dimension del Caso Epstein: El Chantaje.

Como vemos, el caso Jeffrey Epstein introduce una dimensión que excede el escándalo sexual y obliga a pensar en redes de poder. No se trata simplemente de una lista de nombres. Los llamados Epstein files no son un archivo judicial ordenado; son, en buena medida, inteligencia cruda. Y leerlos de manera literal sería un error metodológico. Parte de esa información pudo haber sido producida, exagerada o incluso teatralizada por el propio Epstein en contextos de seducción, chantaje o construcción de prestigio. En entornos donde circulan elites políticas y financieras, la información no solo se registra: se fabrica, se administra y se instrumentaliza.

Por eso la dimensión clave no es solo quién aparece mencionado, sino qué tipo de red operaba allí. Si el objetivo era consolidar una oligarquía transnacional capaz de influir o comprar poder político, la pregunta central es financiera: ¿dónde se movía el dinero? ¿A través de qué bancos? ¿Bajo qué estructuras societarias? ¿Quién garantizaba liquidez y discreción? En ese punto, Wall Street no es un actor periférico. JPMorgan mantuvo relación comercial con Epstein durante años y fue demandado civilmente por víctimas que alegaron que el banco facilitó operaciones financieras que permitieron sostener su estructura. Su CEO alquilo el Salon Dorado del Teatro Colon para festejar hace unos pocos meses. Atención!

La banca internacional no opera en el vacío; opera en el marco de relaciones con clientes de alto patrimonio y alto poder político. Si se quería construir influencia global, el sistema financiero era el vehículo indispensable. Los archivos parcialmente publicados muestran vínculos con políticos, empresarios, académicos y, según diversas investigaciones periodísticas, contactos con entornos de inteligencia. No es necesario afirmar una teoría conspirativa para entender que en el mundo real poder, información y dinero se entrelazan. En el plano político, el representante demócrata Jamie Raskin —miembro del Congreso por el estado de Maryland y protagonista de los procesos de investigación legislativa contra Trump— señaló públicamente que el actual Presidente/Monarca de los Estados Unidos aparece mas de un millon de veces en los documentos liberados hasta el momento que pueden lelgar a ser el 20 por ciento de los documentos existentes.

La cuestión es la siguiente, si una red que combina capital financiero, información sensible y proximidad a figuras de poder político existió —aunque no sepamos todavía su alcance total—, estamos frente a un mecanismo potencial de influencia sistémica. Y si el sistema bancario fue parte del canal por donde circuló ese dinero, entonces el análisis no puede limitarse a individuos: debe extenderse a la arquitectura financiera global. En ese contexto, cuando un presidente impulsa la recentralización de organismos internacionales bajo control ejecutivo, concentra poder frente al Parlamento y mantiene vínculos con circuitos financieros opacos, la pregunta no es anecdótica. Es institucional al mas alto nivel y con el mayor alcance posible. El hecho de que Milei estuviera con Trump mientras se votaba la reforma laboral no es una anécdota de ‘desubicacion’ o ‘ridiculo’, como insiste en plantear el progresismo argentino, sino que es estructural. El Secretario del Tesoro, Scott Bessent, retiene información sobre movimientos bancarios vinculados a Epstein. La pregunta no es solo moral; es estructural. ¿Quién financió qué? ¿Qué bancos facilitaron operaciones? ¿Qué información privilegiada circuló? Donde esta el oro argentino?. Por qué no reacciona el Poder Judicial? Dejen de distraerse con problemas de peronismo autista y empiecen a pensar en términos más abarcativos y, con suerte, programáticos. Si el dinero es la sangre del sistema, los bancos son su sistema circulatorio y, a esta altura, esto es guerra de clases.

Corea del Sur, Brasil y el contraste institucional

Mientras tanto, el ex presidente surcoreano Yoon Suk-yeol fue condenado a prisión perpetua por su intento de autogolpe tras declarar ley marcial. El Congreso actuó, el Poder Judicial intervino y el sistema respondió. En Brasil, Jair Bolsonaro enfrenta procesos judiciales por su intento de desconocer resultados electorales. No es imposible contrarrestar a este neoliberalismo cruel, pero hay que proponerselo en serio y mas alla de la ofensa. Lo que la reforma laboral argentina mostró es que su elite politica (en su totalidad) está comprometida o comprada. Y la combinación de inmunidad presidencial ampliada y control partidario noteamericano se expande a Argentina e intentara bloquear consecuencias penales efectivas para Trump y Milei. Pero acá hay asimetría entre un mundo de poderes que se regulan con democracias mas o menos funcionales y proyectos de emperadores es formacion que no es menor. Para mi, la posicion de Milei y de Trump en este momento es señal de fragilidad institucional y posiblemente de ellos como figuras perpetuables. Pero para poder superar la crisis del post neoliberalismo cruel, hay que mirar de otra manera lo que esta pasando.

El Virrey y el Emperador (Patético y Narcoléptico, Respectivamente)

Para eso, volvamos a Milei cantando con Orbán. Orbán no es un actor marginal. Reformó la Constitución húngara, consolidó control sobre el Poder Judicial y medios, y estableció un modelo de “democracia iliberal”. El genocida Netanyahu fue durante años otro referente de ese bloque. Antes de Bolsonaro y Meloni, estaban Orbán y Netanyahu como laboratorio. ¿Dónde se ubica Argentina en ese mapa? Si la flexibilización laboral es celebrada como triunfo interno, también es prueba de alineamiento externo. Argentina se presenta como laboratorio dócil de un capitalismo sin amortiguadores sociales, dispuesto a ajustar legislación para atraer capital bajo la lógica de “America First” —que en la práctica parece más “Trump First”. Y esa es su debilidad.

La pregunta del título de este post/ensayo no es retórica. ¿Es Milei el virrey de un emperador que se cae a pedazos? Porque el bloque que encabeza Trump muestra fisuras: aliados tradicionales que rechazan su arquitectura paralela, cuestionamientos financieros latentes, concentración de poder que depende cada vez más de fallos judiciales y lealtades partidarias. Si el centro se debilita, la periferia queda expuesta.

El Cambio Cultural

Ahora pasemos a la cuestión cultural. Parte de la juventud que solo vivió en la era de redes sociales muestra menor memoria histórica y menor capacidad de contextualización política. Sin pasado, todo parece nuevo. Sin referencias, la ruptura del modelo laboral histórico —incluso con votos peronistas— se percibe como un episodio más, no como lo que, realmente, es. Cuando la política se reduce a cálculo provincial o a la promesa de reelección en 2027, se pierde la dimensión estratégica. La pequeña transacción —“me dieron una minera”, “me aseguraron fondos”— sustituye proyecto.

La reforma laboral no es solo reforma laboral. El Board of Peace no es solo extravagancia. La réplica estadounidense de la OMS no es un capricho. Los archivos Epstein no son sólo un escándalo sexual. Son piezas —con distintos grados de evidencia y opacidad— de un intento de reorganización sistémica que combina concentración ejecutiva, control financiero, desmontaje institucional y arquitectura paralela internacional.

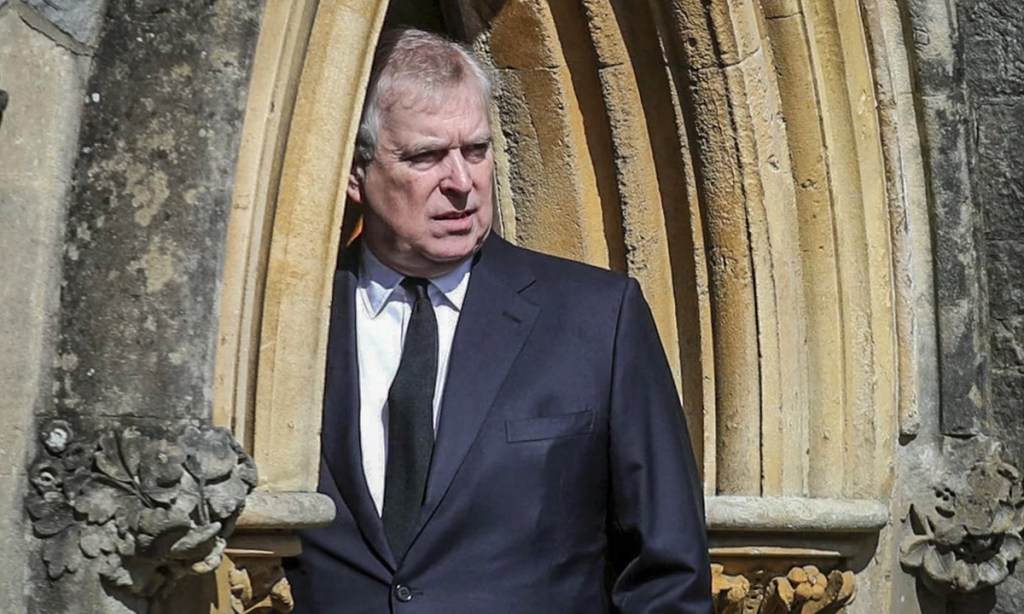

En ese marco, el caso del ex príncipe Andrew deja de ser “farandulización” monárquica y se vuelve un síntoma institucional: si el Estado británico lo llevó por la fuerza no fue por la acusación sexual, sino por el uso indebido de su cargo como enviado comercial y la provisión de información gubernamental no pública a Epstein. La hipótesis que se abre —y que por definición exige cautela probatoria— es la del circuito clásico de la corrupción contemporánea: información clasificada como moneda de cambio para que redes financieras hagan negocios, a cambio de retornos privados, favores o blindajes. Cuando una figura central de la realeza se vuelve comprable y transaccionable en términos de inteligencia y dinero, la brújula moral del sistema se rompe; y el dato políticamente relevante es que, al menos en este punto, el Reino Unido pareció entender que la frontera no era “escándalo” sino seguridad del Estado.

Argentina no está al margen de ese cambio de época. Está adentro. La verdadera discusión no es si la ley laboral fue astuta o imprudente, ni si tal diputado miró al piso. La discusión es si el país está subordinándose a un bloque global cuya cabeza institucional muestra signos de fractura. Si el emperador tambalea, el virrey no hereda el trono. Hereda el vacío pero la pregunta es quien tiene la visión para reconstruir en medio de semejante desierto dirigencial argentino?

© Rodrigo Cañete, 2026. All rights reserved. This text may not be reproduced, distributed, translated, archived, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise—without prior written permission from the author, except for brief quotations used for academic, journalistic, or critical purposes with full attribution.

The Viceroy and the Empire in Free Fall: Does a National Elite (Peronist and Anti-Peronist) Bought by Wall Street Have a Future?

The unitary executive theory, signing statements, Guantánamo, and Trump v. United States (2024) aren’t isolated episodes — they consolidate a president shielded from Congress. When the Executive redraws its own limits, Parliament becomes ornamental. And that model travels.

Tweet

Labour Deregulation and the Global Experiment of Cruel Post-Neoliberalism

The image is obscene in its literalness. While Argentina’s Congress debated—and ultimately passed—the labour-deregulation law, and while unions and social organisations denounced repression in the streets, Javier Milei was shown singing and celebrating alongside Viktor Orbán—prime minister of Hungary and Europe’s laboratory of “illiberal democracy”—and Gianni Infantino—FIFA’s president and a central operator in the politico-financial business of global football—on a stage that Donald Trump was trying to turn into a simulacrum of the United Nations: his Board of Peace, a “parallel UN” in which permanent membership is bought for a billion dollars and the gatekeeper is Trump himself. But the decisive fact is not that Milei was laughing: it is that the host was in a state of performative decline. Trump left delegations waiting while his playlist played, arrived late, began improvising as if disoriented, announced multi-billion allocations he cannot constitutionally approve, and turned the supposed summit into a personalist, erratic, senile spectacle—the kind of scene that should set off alarms in any country presenting itself as his preferred ally.

That “embarrassment” is not gossip. It is the snapshot of a mutation: the United States no longer offers a multilateral order (UN, WHO, shared rules), but a model of outsourced sovereignty, where alignment is purchased, discipline is demanded, and institutional control is replaced by personal loyalties and deals. When Milei sings on that stage at the exact moment Argentina deregulates labour, what we are seeing is not presidential folklore; we are watching a country accept entry as a peripheral experiment into a cruel post-neoliberalism, designed to break internal social shock-absorbers while the imperial centre decomposes and seeks to replace legality with private “clubs” of power.

Argentine labor deregulation isn’t “modernization”: it’s the local piece of a global experiment in cruel post-neoliberalism. Social protections are dismantled to offer “legal certainty” to extractive and financial capital in a fractured world. Argentina isn’t reforming — it’s aligning.

Tweet

That forum—explicitly conceived as an alternative to the United Nations—held its first meeting in Washington in the building of the former U.S. Institute of Peace, informally rebranded the “Donald J. Trump Institute of Peace.” Its organisational scheme establishes that permanent membership requires a contribution of one billion dollars and that Donald Trump concentrates the authority to admit members, define representation, and administer the funds. As of now, there is no public evidence that any country has actually paid that sum. It is a legitimate—and politically explosive—question whether Argentina has committed or will commit resources to that arrangement; so far, there is no confirmation that anyone has paid.

Twenty-seven countries have expressed interest in participating, but the architecture reveals more weakness than strength. The refusal was explicit and coordinated by Austria, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Slovenia, Sweden, the United Kingdom, Ukraine, and the Vatican. That the United Kingdom and the Vatican are on that list is not a minor diplomatic detail: it means the rejection both of a historic nuclear power allied to Washington and of a global moral authority with cross-cutting influence. Canada, moreover, was removed from the scheme after tensions with its leadership at Davos.

Why is the bloc not hegemonic? Because it does not include the central economies of the European Union nor the United States’ traditional strategic partners in the G7. It concentrates neither real financial power nor international institutional legitimacy. What it does gather is something else: governments with authoritarian profiles in consolidation (such as Hungary, Belarus, or Argentina), administrations accused of democratic backsliding, or countries whose economic survival depends critically on access to the U.S. market. It is a club of alignment, not an international order.

Tweet

And the geopolitical map is not accidental. Several of the interested states occupy strategic positions in the containment—or indirect encirclement—of Russia and China, or depend on U.S. protection in regional conflicts. This is not a universalist multilateral bloc; it is a selective network of loyalties inside a great-power competition board. In other words: we are not facing a new UN. We are facing an attempt to redesign international governance as a federation of dependencies.

There was Milei—celebrating.

The Implosion of Argentina’s Political (and Corporate) Elite as Leadership

In Argentina, public conversation got trapped on the surface: who provided quorum, which Peronist governors facilitated the vote, which MPs looked down at the floor while the bill passed. That is the scene dominating television and social media. But precisely the purpose of this blog is to exit that parliamentary soap opera (El Destape, for example) and read the process structurally. Asking which governor “betrayed” is, in the end, a rhetorical question. Nobody votes for a reform of this magnitude by accident; it is voted through out of interest, calculation, or strategic alignment. The real problem is not who betrayed, but what power system makes that betrayal rational.

The labour-deregulation law is not simply a technical reform of the labour market. It is one piece within a broader redesign that we can call cruel post-neoliberalism. It is not the classic 1990s neoliberalism that promised modernisation, openness, and growth under relatively stable global rules. It is harsher: a phase in which social shock-absorbers—labour protections, collective bargaining, the legal presumption of employment—are dismantled to offer international capital a low-cost platform in a world of fierce geopolitical competition. It is not only about lowering “labour costs”; it is about turning peripheral countries into test zones where legal frameworks increasingly favourable to financial and extractive capital are trialled.

In that sense, Argentina is not merely “doing a reform.” It is sending a signal of integration to an international bloc that combines executive concentration, institutional weakening, and the reconfiguration of the multilateral order. Labour deregulation is the domestic gesture of an external alignment.

Epstein isn’t just a sex scandal — it’s raw intelligence plus finance. Partial files, potential blackmail, networks linking politics, academia, banking, and Wall Street. If money buys global power, the real question is financial: where did it move, who enabled it, and who is shielding it now?

Tweet

The first articles alter the presumption of an employment relationship and expand the use of figures like the monotributo (self-employed tax status), weakening the automatic recognition of the employer-employee link. The official argument was structural informality, especially among young people who have never known formal employment. But the systemic effect is different: cheapen labour, flexibilise dismissals, reduce litigation, and offer “legal certainty” to international capital in a context of fierce competition for extractive investment—lithium, energy, mining. The message outward is clear: Argentina is willing to adjust its social legislation to integrate into a bloc that privileges fiscal discipline, extractive openness, and geopolitical subordination.

When I speak of cruel post-neoliberalism I do not mean a slogan. I mean a concrete mutation of global capitalism after 2008, accelerated after the pandemic and the war in Ukraine. The classic 1990s neoliberalism operated within a relatively stable order: WTO, multilateral agreements, extended global value chains, U.S. financial hegemony without open strategic competition. The promise—true or false—was that openness would bring growth.

Today that order is fractured. The U.S.–China rivalry crosses trade, technology, energy, and finance. The war in Ukraine reshaped energy flows. The Indo-Pacific is a permanent tension zone. In that context, peripheral countries are no longer simply “emerging markets”: they are strategic platforms. Argentine lithium is not merely a commodity; it is a critical input for batteries, energy transition, and industrial autonomy. Vaca Muerta’s reserves are not merely hydrocarbons; they are pieces on Western energy security.

Cruel post-neoliberalism operates on this board. It does not promise general wellbeing; it promises macro stability and legal predictability for capital in a volatile world. To achieve it, it reduces labour rights, weakens collective bargaining, flexibilises firing, and limits litigation. Not because it believes in “trickle-down,” but because it competes to attract investment against other jurisdictions equally precarised.

In this scheme, external debt plays a disciplining role. Argentina negotiates permanently with the IMF, issues bonds in international and domestic markets, and depends on the credit of major global banks. JPMorgan Chase is not a decorative actor: it is one of the key structurers and distributors of sovereign debt in emerging markets. When Argentina’s Ministry of Economy speaks with major investment banks—and when the minister himself comes from that bank—it is not simply seeking financing; it is negotiating conditions of insertion into the global financial system.

South Korea sentences its former president for a self-coup. Brazil prosecutes Bolsonaro. In the U.S., Trump remains shielded by immunity and institutional capture. That asymmetry defines the moment: some democracies still enforce accountability — others normalize the emperor. And the periphery pays the price.

Tweet

And that financial system is traversed by the same kinds of networks that appear tangentially in the Jeffrey Epstein case: banking flows, privileged information, ties between political, academic, and business elites. Financial capital does not operate in a moral vacuum; it operates through power networks.

That is why labour deregulation cannot be read as “modernisation.” It is the adaptation of Argentina’s legal framework to a systemic competition in which peripheral countries offer flexible labour, fiscal stability, and legal certainty in exchange for access to capital. In a world where the centre—the United States under Donald Trump—tries to reconfigure or even replace the multilateral order, the periphery becomes the laboratory. The cruelty is not only the content of the reform. It is the context: protections are dismantled in the name of a stability whose institutional head shows signs of decomposition, personalism, and financial capture.

The Monarch-President and the Real Royalty in Custody

To understand the meaning of that signal we have to look at Washington—not only today’s Washington, but the Washington of the last four decades. Since the 1980s, sectors of the Republican Party have developed with increasing systematisation the theory of the unitary executive: the idea that the president, as head of the Executive Branch, concentrates all executive authority and cannot be effectively limited by Congress or by independent administrative agencies. This is not a metaphor. It is a legal doctrine aimed at reconfiguring the balance of powers.

During Ronald Reagan’s presidency, that theory began to take institutional form. His attorney general, Edwin Meese—a conservative lawyer key to the ideological reorientation of the Department of Justice—pushed the idea of strengthening the president against Congress even when polls showed public opinion did not support certain policies. The explicit goal was to guarantee executive continuity even if voters disapproved.

One of the instruments that emerged in that context were signing statements—interpretive declarations upon signing a bill—through which the president formally enacts a law passed by Congress but simultaneously declares how he will interpret it or which parts he considers non-binding. Put plainly: the president signs the law, but announces he will apply it according to his own constitutional criteria. The tool did not originate with Reagan, but under his administration and those that followed it became a political weapon.

That practice reached maximum tension during George W. Bush’s presidency. After the September 11 attacks, the Executive Branch expanded its powers dramatically in the name of national security, and in 2004 the Abu Ghraib torture scandal erupted. Republican senator John McCain, a Vietnam veteran and torture survivor, pushed an amendment explicitly prohibiting cruel and inhuman treatment of detainees in U.S. custody. Congress passed the prohibition. But Bush signed the bill accompanied by a signing statement asserting that the president would retain authority to interpret it in light of his powers as commander-in-chief. In practical terms, the Executive reserved room to continue practices Congress sought to restrict.

Guantánamo—the detention centre at the U.S. naval base in Cuba—became the symbol of that executive expansion: indefinite detentions, special military tribunals, and interrogation techniques international bodies classified as torture.

In parallel, legal figures such as Samuel Alito—then a Department of Justice official and today a justice of the U.S. Supreme Court—contributed to the theoretical argumentation justifying the expansion of presidential power vis-à-vis the Legislature. What in the 1980s seemed like a fringe doctrine began to install itself as a hegemonic conservative current. There were judicial rulings limiting the Executive. But the underlying trend was clear: expansion of presidential latitude in national security and foreign affairs, practical reduction of effective controls, and normalisation of the argument that the president can reinterpret legislative will. The president of the presidential system was becoming a kind of monarch.

When we observe Donald Trump today—his unilateral announcements of billions without congressional approval, his constant appeal to national security to justify disruptive decisions—we are not facing an isolated outburst. We are facing the culmination of a doctrinal trajectory that began forty years ago.

In July 2024, the Supreme Court of the United States ruled in Donald Trump v. United States, and the scope of the decision was far deeper than the media reflected. The Court held that the president enjoys absolute criminal immunity for acts performed within the core of official functions, and presumptive immunity—i.e., difficult to rebut—for other acts connected to the exercise of office. Translated into political language: if the president acts within the frame of “official duties,” he cannot be criminally prosecuted for it.

The problem lies in the definition of “official duty.” Who decides what falls inside that category? The Supreme Court itself. That is, the Court not only expands the Executive’s margin but reserves for itself the power to determine when that margin applies. In parallel, there exists within the Department of Justice a memo—not a law voted by Congress—stating that a sitting president should not be criminally prosecuted while in office. The result is a shielded president: an absolute non-hereditary monarch.

Where does Congress stand in this scheme? Formally, it retains the power to legislate, appropriate funds, and initiate impeachment. But in practice, if the Executive can reinterpret laws through signing statements, invoke national security to expand competences, and rely on a Court that recognises expanded immunity, Parliament is reduced to a conditioned actor. It can pass norms, but the Executive can reinterpret them; it can allocate funds, but the president can announce international commitments under the logic of foreign policy and then force negotiations.

The parallel with Argentina is unsettling. When the Executive accumulates tools to govern by decree, redefines the presumption of an employment relationship, pushes structural reforms in block, and eventually projects constitutional reform, the Legislature is pushed into a reactive position. The question is not whether Congress exists; the question is how much real capacity it has to stop a reconfiguration of the entire system.

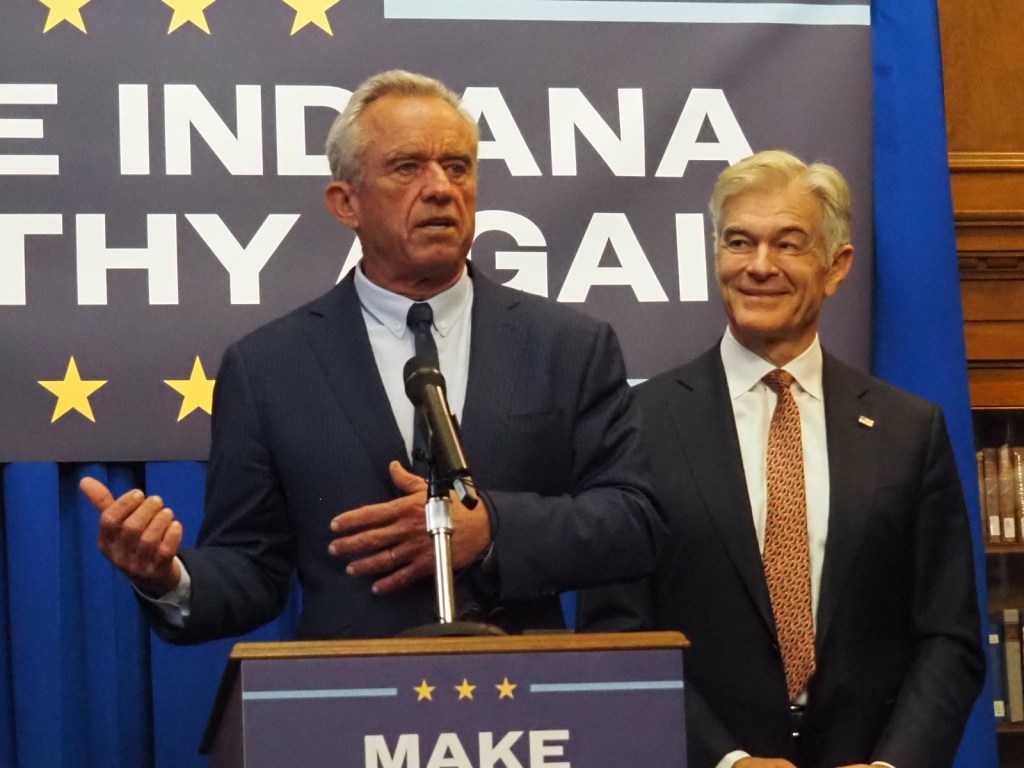

The shielded President/Monarch is the ground on which the next move is built: the creation of parallel structures under direct executive control. Trump not only promoted withdrawal from the World Health Organization; he pushed the creation of a U.S. version under the Department of Health led by Robert F. Kennedy Jr. Kennedy is not a traditional technical official: he is a political figure with a history of confrontation with public health agencies, a promoter of controversial positions on vaccines and medical regulation, and a media personality with cross-cutting ties within U.S. politics.

The project would spend roughly $2 billion annually to replicate functions the United States already financed within the multilateral framework with contributions around $680 million. This is not economic efficiency; it is political control. Exiting the multilateral body—where rules, international oversight, and state cooperation exist—only to recreate it domestically means concentrating global health decisions under national jurisdiction and, ultimately, presidential/monarchical command.

Within this network another name appears that connects to the financial subsoil of power: Mehmet Oz (in charge of Medicaid), known as Dr. Oz, a public figure who entered politics and whose name appears mentioned in materials linked to Jeffrey Epstein. Likewise, JPMorgan Chase maintained a banking relationship with Epstein for years and was sued for its role in facilitating accounts and transfers. In judicial materials, when Epstein was asked about his link to John Mack—former CEO of Morgan Stanley and a central figure on Wall Street—Epstein invoked the Fifth Amendment, which protects against self-incrimination. In other words, he refused to answer. The currency in that circuit was not only money; it was information—financial information, political information, sensitive information.

The pattern is coherent: executive concentration, weakening of legislative controls, creation of parallel structures under presidential command, and the circulation of financial networks where global banks and political elites interact. This is not saving. This is not efficiency. It is recentralisation and control within a context of systemic global competition.

The Other Dimension of the Epstein Case: Blackmail

As we can see, the Jeffrey Epstein case introduces a dimension that exceeds the sexual scandal and forces us to think in terms of power networks. It is not simply a list of names. The so-called Epstein files are not an ordered judicial archive; they are, to a large extent, raw intelligence. Reading them literally would be a methodological error. Part of that information may have been produced, exaggerated, or even theatricalised by Epstein himself in contexts of seduction, blackmail, or prestige-building. In environments where political and financial elites circulate, information is not only recorded: it is manufactured, managed, and instrumentalised.

That is why the key dimension is not only who is mentioned, but what kind of network operated there. If the objective was to consolidate a transnational oligarchy capable of influencing or buying political power, the central question is financial: where did the money move? Through which banks? Under what corporate structures? Who guaranteed liquidity and discretion?

Here, Wall Street is not peripheral. JPMorgan Chase maintained a commercial relationship with Epstein for years and was sued civilly by victims who alleged the bank facilitated operations that sustained his structure. Its CEO rented the Golden Hall of the Teatro Colón to celebrate just a few months ago. Attention.

International banking does not operate in a moral vacuum; it operates through relationships with high-net-worth, high-power clients. If one wanted to build global influence, the financial system was the indispensable vehicle.

Partially published files show ties with politicians, businesspeople, academics and, according to various journalistic investigations, contacts in intelligence milieus. You do not need to assert a conspiratorial theory to understand that in the real world power, information, and money intertwine.

Politically, Representative Jamie Raskin—a Democratic congressman from Maryland and a protagonist in congressional investigations into Trump—publicly stated that the current President/Monarch of the United States appears more than a million times in the documents released so far, which may amount to only 20% of the total existing documents. The point is this: if a network combining financial capital, sensitive information, and proximity to political power existed—even if we do not yet know its full scope—then we are facing a potential mechanism of systemic influence. And if the banking system was part of the channel through which that money circulated, then the analysis cannot be limited to individuals; it must extend to the global financial architecture.

In that context, when a president pushes the recentralisation of international organisations under executive control, concentrates power against Parliament, and maintains ties to opaque financial circuits, the question is not anecdotal. It is institutional at the highest level and with the broadest possible reach. The fact that Milei was with Trump while the labour reform was being voted is not an anecdote of “inappropriateness” or “ridiculousness,” as Argentine progressivism insists on framing it; it is structural. Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent is holding information on banking movements linked to Epstein. The question is not only moral; it is structural. Who financed what? Which banks facilitated operations? What privileged information circulated? Where is the Argentine gold? Why doesn’t the judiciary react? Stop getting distracted by the problems of an autistic Peronism and start thinking in strategic terms. If money is the bloodstream of the system, banks are its circulatory system.

South Korea, Brazil, and the Institutional Contrast

Meanwhile, former South Korean president Yoon Suk-yeol was sentenced to life in prison for his attempted self-coup after declaring martial law. Congress acted, the judiciary intervened, and the system responded. In Brazil, Jair Bolsonaro faces judicial processes for his attempt to deny electoral results.

It is not impossible to counter this cruel post-neoliberalism, but it requires seriousness beyond outrage. What Argentina’s labour reform showed is that its political elite (in its entirety) is compromised or bought. And the combination of expanded presidential immunity and U.S. party control expands into Argentina and will attempt to block effective criminal consequences for Trump and Milei.

But there is asymmetry between a world of powers that regulate themselves through more-or-less functional democracies and projects of emperors in formation. For me, the position of Milei and Trump right now is a signal of institutional fragility and possibly of their weakness as “perpetuable” figures. But to overcome the crisis of cruel post-neoliberalism, we have to look differently at what is happening.

The Viceroy and the Emperor (Pathetic and Narcoleptic, Respectively)

For that, let’s return to Milei singing with Orbán. Orbán is not a marginal actor. He reformed Hungary’s constitution, consolidated control over the judiciary and the media, and established a model of “illiberal democracy.” The genocidal Netanyahu was for years another reference point of that bloc. Before Bolsonaro and Meloni, Orbán and Netanyahu were the laboratory.

Where does Argentina sit on that map? If labour deregulation is celebrated as a domestic triumph, it is also proof of external alignment. Argentina presents itself as a docile laboratory of capitalism without social shock-absorbers, willing to adjust legislation to attract capital under the logic of “America First”—which in practice looks more like “Trump First.” And that is its weakness.

The question in this post/essay’s title is not rhetorical. Is Milei the viceroy of an emperor who is falling apart? Because the bloc Trump heads shows fissures: traditional allies rejecting his parallel architecture, latent financial questions, concentration of power increasingly dependent on court rulings and partisan loyalties. If the centre weakens, the periphery is exposed.

The Cultural Shift

Now let’s move to the cultural question. Part of the youth that has only lived in the era of social networks shows less historical memory and less capacity for political contextualisation. Without the past, everything seems new. Without references, the rupture of the historic labour model—even with Peronist votes—appears as just another episode, not as structural change.

When politics is reduced to provincial calculation or the promise of reelection in 2027, strategic dimension is lost. The small transaction—“they gave me a mining concession,” “they guaranteed me funds”—replaces project.

Labour reform is not only labour reform. The Board of Peace is not only extravagance. The U.S. replica of the WHO is not a whim. The Epstein files are not only a sexual scandal. They are pieces—with varying degrees of evidence and opacity—of an attempt at systemic reorganisation that combines executive concentration, financial control, institutional dismantling, and parallel international architecture.

In that frame, the case of the former Prince Andrew stops being monarchic “tabloidisation” and becomes an institutional symptom: if the British state forced him into custody, it was not for the sexual accusation, but for misuse of his position as trade envoy and the provision of non-public government information to Epstein. The hypothesis that opens—requiring caution by definition—is the classic circuit of contemporary corruption: classified information as currency so financial networks can do business, in exchange for private returns, favours, or shields. When a central figure of royalty becomes purchasable and tradable in terms of intelligence and money, the moral compass of the system breaks; and the politically relevant datum is that, at least here, the United Kingdom seemed to understand the frontier was not “scandal” but state security.

Argentina is not on the margins of this change of era. It is inside it. The real discussion is not whether the labour law was shrewd or imprudent, nor whether some MP looked at the floor. The discussion is whether the country is subordinating itself to a global bloc whose institutional head shows signs of fracture. If the emperor wobbles, the viceroy does not inherit the throne. He inherits the void—but the question is who has the vision to rebuild in the middle of such a desert of leadership in Argentina?

© Rodrigo Cañete, 2026. All rights reserved. This text may not be reproduced, distributed, translated, archived, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise—without prior written permission from the author, except for brief quotations used for academic, journalistic, or critical purposes with full attribution.

Deja una respuesta