On March 24th, Argentina observed its annual day of remembrance for the disappeared. Official commemorations often rely on a fixed narrative: the dictatorship as an irreparable tragedy, the Never Again as a closing statement, aiming to prevent repetition. However, the problem with official memory politics is its attempt to encapsulate the past within a rigid, static narrative that becomes repetitive and morally unyielding. Rather than creating a space for deep reflection, this commemoration has turned into a reaffirmation of democratic values, leaving aside the complexities of historical processes and ongoing societal tensions.

The problem with official memory politics is its attempt to encapsulate the past within a rigid, static narrative that becomes repetitive and morally unyielding.

Tweet

Consensus as Politically Correct

Those like Argentine President Javier Milei who argue over the number of victims—engaging in a cold calculation—fail to explore alternative ways to intervene in memory. True memory is not just a fixed narrative; it should actively interrogate the present, offering new perspectives. This is particularly urgent as we see the rise of fascist ghosts both locally and globally, with the collapse of economic promises threatening to reintroduce a manichean divide between “us” and “them.” This binary of good and evil ultimately leads to “consensus” or, worse, “politically correct” views, which reproduce a domesticated memory. This static memory repeats familiar phrases without confronting the structural amnesia pervasive in our culture.

True memory is not just a fixed narrative; it should actively interrogate the present, offering new perspectives. This is particularly urgent as we see the rise of fascist ghosts

Tweet

In Argentina and the art market, in general; contemporary art often participates negatively in this dynamic. Although it may address the past, it tends to do so through pleasant, pre-decoded images of trauma. The works of elite artists, such as the “smiling” figures in art gatherings and openings, reveal a troubling disconnect: these works are celebrated without addressing the violence they embody, functioning more as a visual spectacle than as a force for critical reflection.

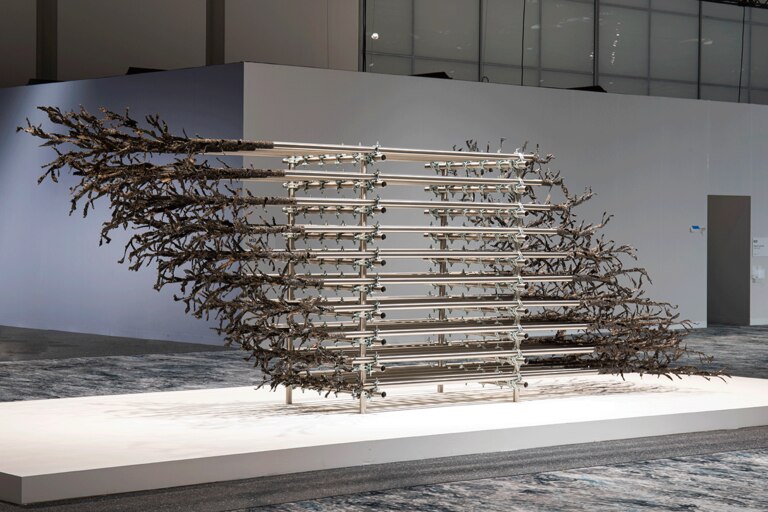

Art should intervene in the dominant temporality, disrupting the present and offering new ways of perceiving history. Instead, many works remain confined to the elite art world, circulating within galleries and biennials without challenging the prevailing structures. Take, for instance, Argentine Luciana Lamothe’s work, which, despite its conceptual efforts to tension bodies and materials, ultimately remains a formal exercise, detached from the broader social fabric or the politics of memory.

A striking example of the entrenchment of the status quo is Pablo Rosales’ work with Judge Bruzzone. As analyzed previously, Rosales’ work documents a closed, self-referential scene where members of the same elite circle reinforce their own narratives without questioning the power dynamics that shape memory. In this context, Rosales’ art does not disrupt the structures of power that govern memory; it perpetuates them, becoming part of the system that manages this memory without challenging its course.

Challenging Our Conventional Understanding of History

The work of the Otolith Group, Alham Shibli, Hito Steyerl, and Steve McQueen, however, offers a different approach. These artists do not present the past in a linear, nostalgic way but interrupt it, reintroducing it through spectral forms that challenge our conventional understanding of history. Their works refuse to offer simple representations; instead, they create a politics of temporality that questions the linearity of history, making room for multiple memories and untold futures.

The work of the Otolith Group, Alham Shibli, Hito Steyerl, and Steve McQueen do not present the past in a linear, nostalgic way but interrupt it, reintroducing it through spectral forms that challenge our conventional understanding of history.

Tweet

The Otolith Group’s Nervus Rerum (2008) exemplifies this approach. Set in the Jenin refugee camp, the work avoids traditional documentary grammar, offering a layered experience where voices and images coexist without clear resolution. It does not show present suffering but rather makes visible how time itself has been damaged. Similarly, Alham Shibli’s photographs of Palestinian martyrs and unrecognized Bedouin villages challenge the hegemonic forms of the archive. Instead of monumentalizing grief, she captures fleeting, intimate moments, refusing to allow power to erase history.

Hito Steyerl’s How Not to Be Seen critiques the total visibility of the digital age, where images are archived and erased in real time. Her work questions how history has been replaced by flows of memory-less images, using strategies of invisibility as both political and aesthetic survival. Steve McQueen’s Western Deep offers another form of intervention, using the body as an archive in the South African gold mines. The work does not narrate but immerses the viewer in the repetition of labor, experiencing history as fatigue, as a colonial present that endures without resolution.

These works stand in stark contrast to the institutionalized Argentine art scene, which often reduces the past to a superficial aesthetic. In the context of Argentina, memory has become a spectacle rather than a space of confrontation. Instead of challenging the political and social structures that shape how we remember, much contemporary Argentine art becomes a tool for reinforcing these structures. In contrast, the works of Otolith, Shibli, Steyerl, and McQueen don’t just represent history—they disturb it, opening up a space where memory is not fixed but continuously redefined.

In conclusion, the most powerful operation that art can perform is to disorganize time. Rather than simply representing the past, art should intervene in the present, challenging our perceptions of history and memory. In a country like Argentina, where memory has been institutionalized into fixed rituals, the role of art is to disrupt, to interrogate, and to transform the power structures that shape how we remember.

Deja una respuesta