The forehead of Marina de Achával and Eva Soldati’s cheeks deserve several posts on their own. But let’s begin with Marina’s forehead: what does it reveal, and what does it hide?

On the surface, Marina de Achával claims to be a fashion designer, like her sister, with the style of a wronged wife whose looks cost her husband dearly. But nothing could be further from the truth. She’s known for belonging to a traditional family from Argentina’s aristocracy, and even more so for being La Vampiracha, the muse of LANP (this blog). That’s why she appears in certain high-profile social scenes. In other words, she doesn’t need to work to live — which is both wonderful and problematic. Her figure embodies a kind of elegant, discreet, patrician femininity, like a haughty heiress who —unlike the gatanas— always overdresses, but in a different register.

Two Sadists?

Marina de Achával was married to Francis Mallmann, and they share a daughter. Their relationship was widely discussed in Buenos Aires’s social circles, as it brought together two emblematic figures: he, the eccentric, media-friendly chef; she, the discreet bohemian aristocrat. Also, she was extremely, almost cartoonishly, cheated on.

In many ways, Marina is the aesthetic antithesis of Mallmann: neo-Gothic, translucent white, urban, and seemingly indifferent to spectacle — while he is desperately star-struck and fame-hungry. In alchemical terms, he’s all fire; she is ice and shadow. Their bond seemed to hinge on that tension between worlds: her introspective luxury versus his performative luxury. What was hidden beneath it was a deeply incompatible relationship with a certain sadistic undercurrent.

Francis Mallmann’s public persona inspires fascination and disgust in equal measure. His reputation as a “bad person” isn’t a matter of legal or moral record, but a cultural construction based on his public persona, his statements, and his manner.

Why does Mallmann have such a reputation for being a bad person?

His giant chef-ego persona: Mallmann has cultivated the image of a dandy chef — solitary, authoritarian, capricious, narcissistic — a kind of decadent bon vivant. In interviews, he’s said things like he doesn’t enjoy hosting poor people, or that humble people are “boring.” Naturally, that offends.

The Imperial Cepoy

He despises popular culture, yet uses it: His aesthetics are rustic — fire, earth, potatoes in the ground — but they’re framed through a lens of exoticization and exploitation. He charges astronomical sums for food in a country mired in structural poverty. There’s something undeniably colonial in his pose, though in his case, it’s a form of internalized colonialism — the colonized man playing the imperial lord.

How he treats his staff: While there are no major public complaints, many describe him as cold, top-down, unaffectionate, lacking empathy. He promotes the idea that geniuses don’t need to be kind. If he had to identify with someone, it would be Picasso — though the differences are, let’s say, massive.

Misogynistic or snobbish remarks: He’s said things like he enjoys having many women but prefers living alone, or that fidelity is boring — all from a place that naturalizes emotional inequality as if it were some kind of existential depth. The kicker? He said this while married.

What’s worst, arguably, is the way he presents himself: always with the aura of a detached millionaire, with a vaguely Nazi accent. He lives in remote locations, gives interviews from his private island, sneers at urban life and mass culture, and seems more like an 18th- or 19th-century German aristocrat than a contemporary chef. He mixes fantasy and fiction — and for a while, it worked. But now, it’s out of fashion.

In short, there’s no concrete proof he’s a “bad person” in any legal or ethical sense, but he has built a persona that, to many, embodies the worst of bourgeois-bohemian masculinity: egocentric, arrogant, elitist, and emotionally absent.

Michelangelesque Racialised Botoxed Posthuman Subjectivities

This obviously took a toll on poor Vampiracha, who resolved everything with Botox — a kind of Kabuki mask that hides pain and smooths out the foreheads of very white women like her, thanks to two key factors: the chemical action of Botox on the muscles, and the optical characteristics of very light skin. The toxin paralyzes the muscles responsible for dynamic wrinkles, and fair skin, by reflecting more light, enhances the effect of a smooth, almost marble-like surface.

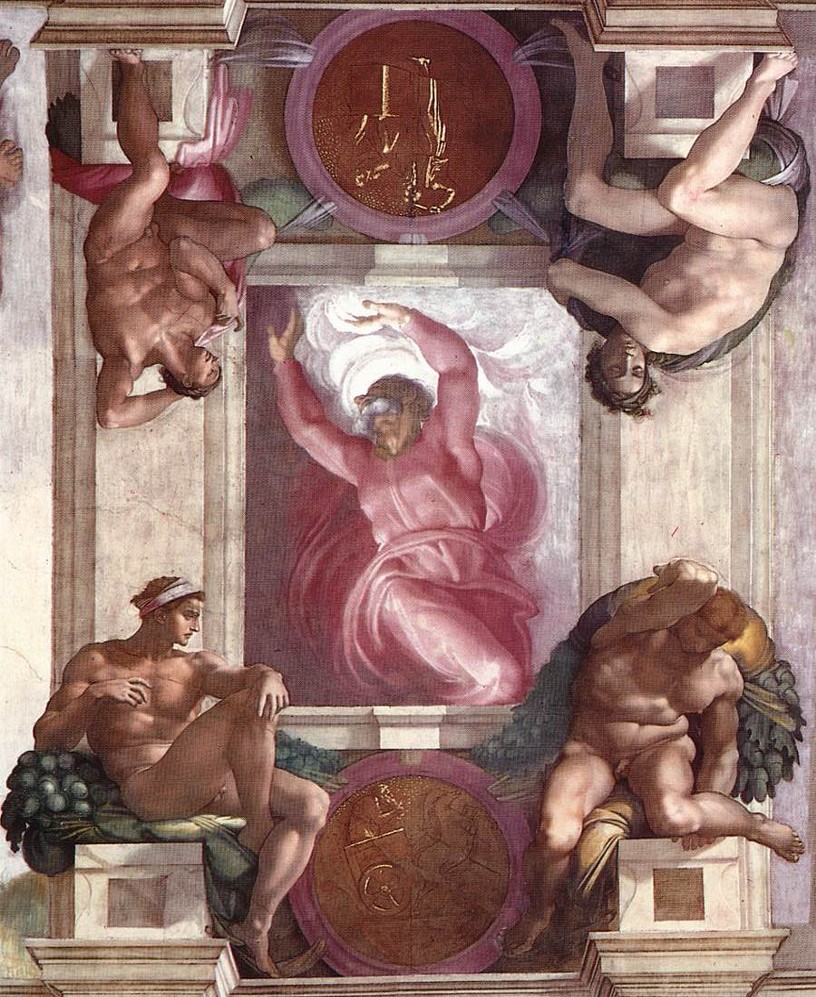

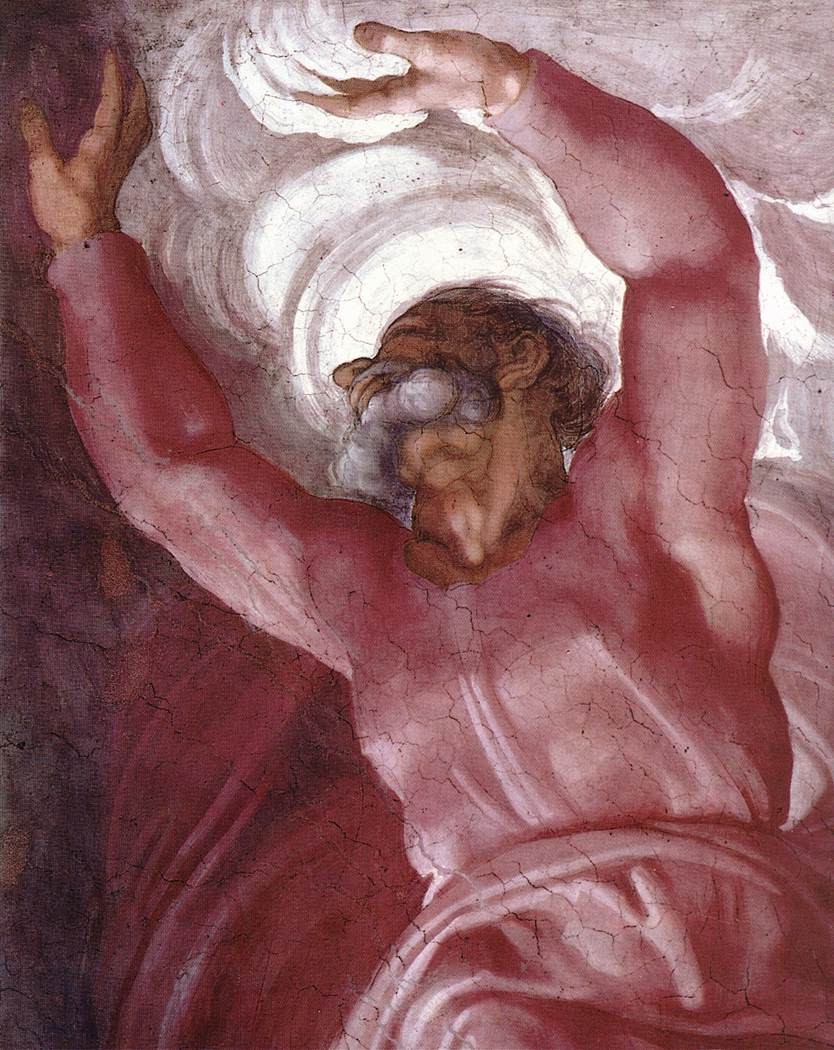

And here’s where Marina’s sadism comes in. This obsession with total smoothness recalls Michelangelo’s fascination with white sculpture, with the purity of marble, and with that idealized whiteness seen in the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. There, whiteness symbolizes purity, divinity — a surface without blemish, as if whiteness were the reflection of perfection and eternity. And this being Argentina, that doesn’t place her far from her ex at all.

This obsession with whiteness echoes the unsettling racism of Sarmiento’s Facundo. Just as Botox erases the signs of time and emotion, the racial ideal of purity attempted to erase the diversity and complexity of the mestizo, the Indigenous, and the Afro-Argentine. A smooth, homogeneous surface, with no folds or textures. Like Botox, racism seeks a fictitious perfection at the cost of eliminating diversity. Thus, the smoothed forehead of contemporary white women and Michelangelo’s pure marble converge with Facundo in a shared obsession: a surface that erases time’s marks and human complexity.

Marina embodies a post-human, ethereal, almost vegetal version of the present. Her aesthetic is not cyborg, but botanical. There’s no expression — only outline. No emotion — only textile silence. She dresses as if she didn’t want to touch the world, as if her body were a curated, scentless interface. It’s not about youth or beauty, but emotional economy: don’t interfere, don’t sweat, don’t affect. Her fashion flows as if the body didn’t ache.

Mallmann, in contrast, is pure material drama: fire, grease, smoke, wine. He cooks as if summoning a lost past. His gesture is nostalgic, but not tender — it’s masculine, colonial, excessive. Each dish seems like a ritual to delay the end of the world, a scene of power and memory where he places himself at the center. His nostalgia is a longing for permanence, for authorship, for historical weight.

She erases history with forced elegance; he reproduces it with theatricality — the opposite of elegance. She vanishes; he insists on appearing, even when unwanted. And in that difference — between one who no longer wants to be a body, and one who refuses to stop being one — lies an uncomfortable question for us all, and a life lesson from this ex-couple:

Do we want to live lighter or more intensely? To disappear softly or to burn to the end?

© Rodrigo Canete, 2025]. All Rights Reserved

Todos los contenidos de este blog están protegidos por la legislación internacional sobre derechos de autor, incluida la Convención de Berna. Queda prohibida su reproducción total o parcial sin el consentimiento expreso de la autora. En caso de cita o referencia, se exige mención clara de la autoría y enlace al sitio original.

Deja una respuesta