Mystical Simulacrum as Real-Estate Décor: On Daniel Leber at Malba Puertos, the New Gentrified Greenwasher Project in the Affluent Northern Buenos Aires Metropolitan Area

The exhibition Xul Solar and Daniel Leber: Infinite Flight, recently inaugurated at Malba Puertos, attempts to draw a line of continuity between the mystical visions of Xul Solar and the work of contemporary artist Daniel Leber. Yet rather than a spiritual bridge between two eras, what is offered is a symbolic set dressing that legitimizes an elite urban development experiment. The curatorial narrative proposes an alliance between art and transcendence, but the result is an alliance between art and capital gains.

Like Aleister Crowley or Kandinsky, Xul sought to connect with occult forces in order to reorder a broken world. His esoteric practice had a revolutionary, subversive, even heretical dimension.

Tweet

It is crucial to ask what sense this contemporary resurgence of symbols, astrology, and alchemical imagery makes. In Xul’s time, these languages responded to a civilizational crisis: they were vehicles for a spiritual reinvention of the world in the aftermath of the symbolic collapse triggered by World War I. Like Aleister Crowley or Kandinsky, Xul sought to connect with occult forces in order to reorder a broken world. His esoteric practice had a revolutionary, subversive, even heretical dimension. Like Crowley, Xul invented systems, languages, rituals, and symbols to challenge the established order and access alternative realities through a delirious yet critical spirituality.

Leber positions himself within a culture of mindfulness understood as a neo-Stoic technique of self-control.

Tweet

Today, that same repertoire survives only as surface. Leber’s images are far from visionary quests: they are more like illustrations of a wellness spirituality, tailored to the codes of the art market and urban development. Instead of a plunge into the abyss, what we see is an aesthetic of emotional balance, regulated harmony, and the self as a project of self-optimization. Leber positions himself within a culture of mindfulness understood as a neo-Stoic technique of self-control: a way of managing affects and reducing dissent, not of opening up to mystery or confronting the structure of the present.

This logic becomes evident when looking closely at his work. In Nuestros hijos (Our Children, 2020), Leber presents a scene reminiscent of sacred art, but with displaced icons: androgynous figures are connected by golden threads, floating in a flat, stellar background. The painting aspires to the cosmic but evokes no real vertigo: its symmetry and sealed composition deny the delirium and excess that, in Xul, were conditions for mysticism. Leber replaces trance with optical comfort.

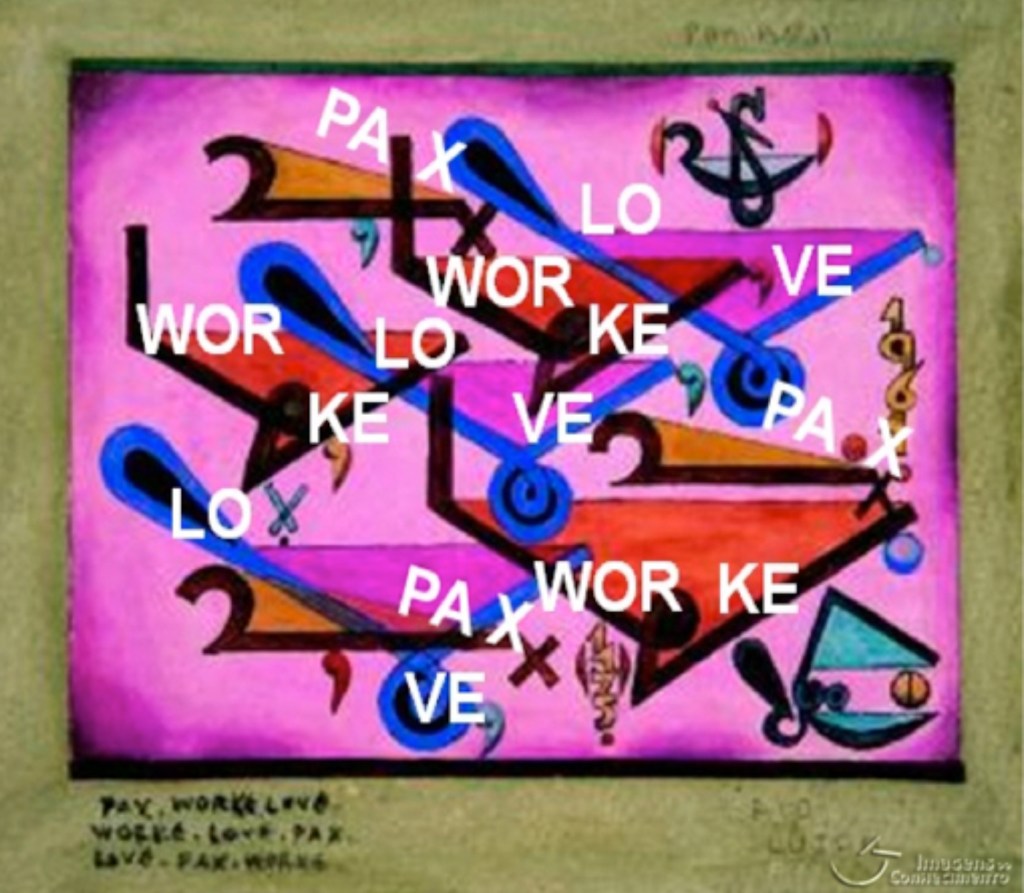

The contrast with Xul is sharp when compared, for instance, with Pax, Worke, Love (1961), where the fusion of words, geometric forms, and alchemical signs opens up interpretive paths rather than closing them. Where Xul’s symbols multiply meaning, Leber’s shut it down. Pax, Worke, Love suggests that peace, work, and love are coordinates within a spiritual experience that resists fixed interpretation. Nuestros hijos, by contrast, seems engineered for immediate impact and broad approval: its spirituality is aesthetic, not epistemic.

A similar divergence emerges between Boske (1931)—Xul’s rendering of a psychic forest where organic shapes intertwine with impossible geometries—and Leber’s installation Aquí no hay allá (Here Is Not There, 2024), composed of symbolic objects (a house of cards, a metal ladder, animal figures) presented as literal metaphors. What in Xul was a semantic jungle becomes, in Leber, a catalogue of metaphors: ascent, fragility, transformation—laid out like an infographic of the spirit. Nothing is hidden; everything is explained. The symbol no longer encrypts, it only signals.

In his three-dimensional sculptures—a hyperrealistic house of cards, a floating constellation of objects—the symbolic gesture becomes literal. Each form points to a clear idea (ascension, instability, connection), without ambiguity or opacity. There is no polysemy here, only a didactic sublime. The works don’t demand reading but contemplative consumption: everything is given, available, digested. Whereas Xul made the viewer into an initiate, Leber only requires them to be a culturally sensitive consumer.

Even more telling: where Xul sought to refound the human through the magical, here magic is at the service of capital. Xul was an esoteric recluse in a still-swampland Tigre, turning the delta into a cosmic observatory. Today, Leber exhibits in an idealized mock-city financed by Eduardo Costantini—the true magician behind this tale. If Xul saw himself as an alchemist of the soul, Costantini is an alchemist of capital: he turns emptiness into value, land into assets, spirituality into branded narrative. In this sense, Infinite Flight is not an exhibition, but a consecration: the enthronement of Costantini as high priest of a luxury esotericism that needs art to legitimize itself.

It is not Leber who dialogues with Xul. It is real estate development that parasitizes his imaginary. The show does not celebrate Xul—it neutralizes him, transforming him into a patriarch of a spiritualized capitalism. Where Xul opened portals, Leber builds bridges—not toward other realities, but toward amenities. This is not vision; it’s visualization. Not mysticism, but marketing. And if the universe was ever magical, today it is managed through homeowner fees.

Deja una respuesta