Cultural Elites, Political Power and Complicity

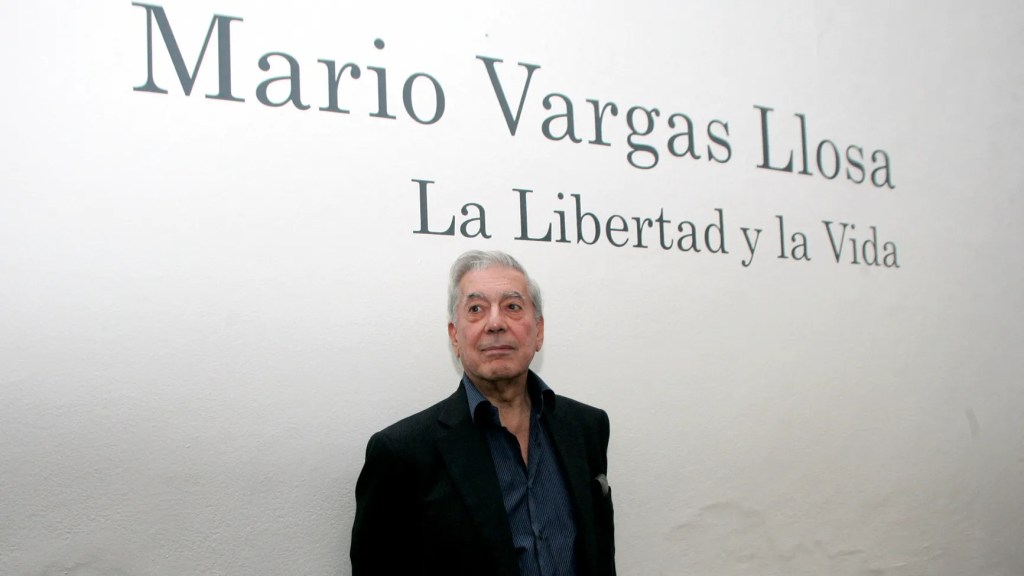

Mario Vargas Llosa has died, the last great representative of a Latin American liberal intelligentsia that always preferred the comfort of elites over the discomfort of truth. Nobel Prize in Literature, celebrity of the Latin American literary boom, and passionate defender of the free market. Up to this point, despite ideological differences, one might still nod in respect. The problem begins when his “proper” place positioned him within structures of power that harmed others—and there, he was a major son of a bitch. And by major, I mean, major.

I say this because behind the façade of literary humanism and paeans to democracy, he concealed a deeply conscious ethical dualism about the role of culture in the erasure of memory—especially inconvenient memories. He used his fame to shield privilege and to aestheticize violence with impeccable prose.

The Soft Face of Selective Collective Amnesia

Carmen Berenguer, along with Diamela Eltit and Raquel Olea, brought to the 1987 Latin American Congress of the Feminine Language a woman who, in a brilliant book called Cruel Modernity, called him out with precision. She had the courage and the authority to do it. Her name was Jeanne Franco, a major academic and Latin Americanist. In that book (which I highly recommend), she showed that Vargas Llosa wasn’t a mere spectator of Latin American political violence: he was an active agent in its asymmetrical narration.

In Peru, Mario Vargas Llosa’s role in the official investigation of the Uchuraccay massacre (1983) laid bare his operating method. Instead of listening to the Indigenous victims—whom he ignored—with courtesy, he administered his cruelty favouring the perpetrators.

Tweet

In Peru, his role in the official investigation of the Uchuraccay massacre (1983) laid bare his operating method and was deeply harmful. There he demonstrated his pattern: denounce horror without disturbing the State; condemn acts without dismantling structures. Instead of listening to the Indigenous victims—whom he ignored—he chose to uphold Lima’s civilizing narrative, the same one that decades later would be used to justify the systematic repression of popular sectors under neoliberal governments. His cruelty was administered with courtesy and style: murder became error, massacre became excess.

Mario Vargas Llosa Inexcusable Collaborationism

In Argentina, his presence left less literary but no less serious traces. In 2016, he accepted an invitation from then-Minister of Culture Darío Lopérfido (who hadn’t even completed high school), a man who had publicly downplayed the number of desaparecidos during the dictatorship. Vargas Llosa not only failed to question this revisionist operation, he legitimized it with his silence and even invited Lopérfido to join his foundation project.

In 2016, Vargas Llosa accepted the then-Minister of Culture Darío Lopérfido (who hadn’t even completed high school), a man who had publicly downplayed the number of desaparecidos during the dictatorship. Later, he invited Loperfido to join him in his foundation.

Tweet

Today, even progressive outlets like El Destape are celebrating Vargas Llosa (“despite some differences”). But Vargas Llosa’s actions during the trials of perpetrators of mass rape and massacres in Peru put him outside that category. This points to a growing problem: the role of the cultural sector in Latin America as a legitimizer of authoritarian practices—whether populist or neo-Nazi. Let’s be clear: Vargas Llosa used his “respectability” as an international seal to justify a soft form of denialism—the kind that doesn’t deny but casts doubt; doesn’t accuse but insinuates. In his brand of liberalism, everything fit except radical memory, restorative justice, or the actual names of the executioners. Just look at Peru today, and its political system.

The International Foundation for Freedom, which he chaired until the end of his life, functioned as the political arm of this ideology: it promoted ultraliberal economists, protected former officials from repressive regimes, and celebrated figures of the new global right under the guise of “defending democracy.” It wasn’t a foundation but a shielding platform for corporate interests, Washington-aligned think tanks, and extractivist capital lobbies. Vargas Llosa was its elegant face, its star speaker, the writer who knew how to turn neoliberalism into a personal epic.

Mario Vargas Llosa’s International Foundation for Freedom wasn’t a foundation but a shielding platform for corporate interests, Washington-aligned think tanks, capital lobbies and extractivism. This might explain his blanking of indigenous people.

Tweet

From Bohemia to Courtly Pathos

In his private life, his transition from literary bohemia to courtly pathos was as marked as his ideological shift. From rebellious youth to conservative old man, his figure became a caricature of itself: amidst media scandals, flings with Spanish royalty, and speeches at business forums, the author of The Time of the Hero ended up closer to Madrid’s bankers than to Latin America’s young writers. Posterity will likely remember him for his novels. But it would be just to remember him also for his discomfort with subaltern bodies, for his silence in the face of horror’s numbers, and for having used literature as a shield—never as a wound.

None of this denies the power of his early work. Conversation in the Cathedral is without doubt one of the most important novels of the 20th century in Spanish, and The Green House displays a narrative architecture that renewed Latin American realism. At that time, Vargas Llosa was a writer engaged with the complexities of power, with the contradictions of desire, and with the structural violence of the State. But that lucidity faded as the author became a public figure, an occasional essayist, and finally, a custodian of the neoliberal order. His literature, like his ideology, became predictably correct—functional to the very system he once challenged.

In his final decades, his novels were mere shadows of his original talent: self-pastiches, bureaucratic narratives that accompanied his international tours and his columns in El País. His investment in structural correctness and liberal morality made his work lose its edge, its imagination, and its risk. The epic of power was replaced by a nostalgia for order. Like so many writers aged by their own dogmas, Vargas Llosa chose to become a monument in life—even if that meant turning to stone.

He died as he lived his last years: surrounded by his kind—businessmen, ex-presidents, right-wing editors, and uncrowned kings. Maybe, in the pantheon of enlightened liberals, someone will write on his tombstone: Here lies a man who defended liberty… as long as it didn’t trouble the owners of the world.

Deja una respuesta