The Legal Erasure of Trans Women in the UK

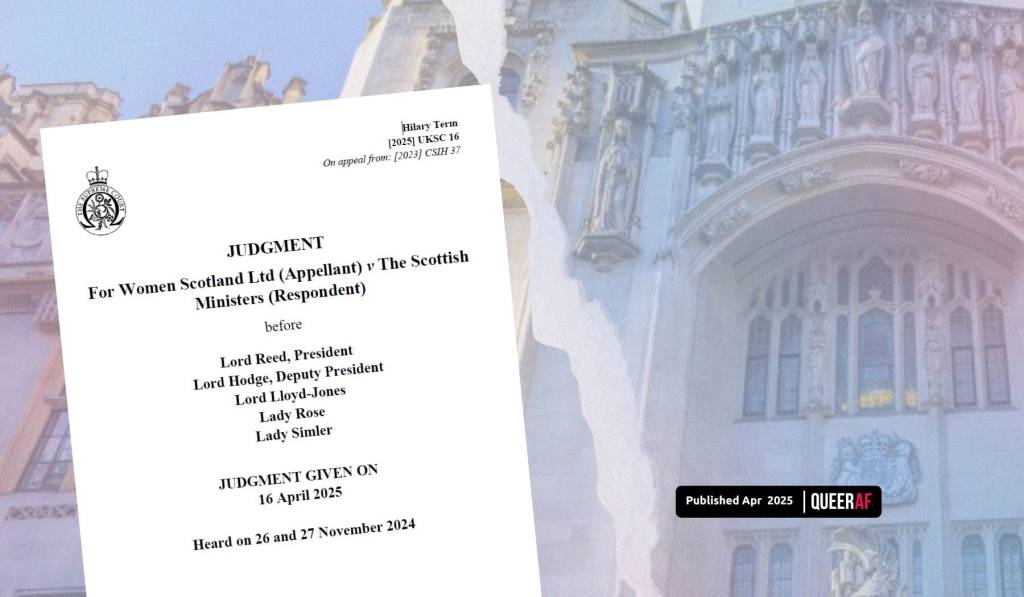

On April 16, 2025, the UK Supreme Court issued a unanimous ruling that redefined the legal meaning of “woman” under the Equality Act 2010. In the court’s view, “sex” refers strictly to biological sex assigned at birth. Even trans women who hold Gender Recognition Certificates—who have undergone full medical transition and are legally recognised in every other context—are now excluded from the legal protections designated for women.

The Supreme Court ruling on Transexuals is not about safety. It is about ideology. About cultural boundaries dressed up in legal robes. It marks a shift—not toward clarity, but toward sanctioned erasure.

Tweet

The ruling arose from a challenge by the gender-critical group For Women Scotland, which objected to the inclusion of trans women in legislation around gender representation. But while the court insists trans people still hold legal “protections,” the infrastructure of that protection has been hollowed out. The language of inclusion remains; the reality of exclusion is now codified.

This is not about safety. It is about ideology. About cultural boundaries dressed up in legal robes. It marks a shift—not toward clarity, but toward sanctioned erasure.

From Ventriloquism to Gatekeeping: Jane Harris and the Problem of Narrative Property

Among those shaping the ideological terrain for this decision are white liberal feminist writers whose cultural capital depends on narrating otherness while defending the borders of their own category. Take Jane Harris, author of Sugar Money, a novel written in the voice of an enslaved Black teenager. Set in the 1760s and inspired by a historical episode in the French Caribbean, the novel was shortlisted for a few prizes and praised for its ‘lyricism’. The Guardian called it ‘a literary coup,’ while The Times described it as ‘irresistibly vivid.’ Houston, we have a problem!

Jane Harris, a militant liberal feminists wrote Sugar Money, a novel set in the XVIII century, written in the voice of an enslaved Black teenager. It was quickly denounced as racial ventriloquism, another example of how white liberal authors gain prestige by speaking as the marginalised, while reinforcing their own ‘ethical’ authority.

Tweet

Yet Black critics and readers raised concerns. In Wasafiri, Bernardine Evaristo wrote of the discomfort in hearing “pain historicised and re-performed by someone who has not inherited it.” The novel’s voice—crafted in a stylised Creole English—was seen by some as racial ventriloquism, another example of how white liberal authors gain prestige by speaking as the marginalised, while reinforcing their own authority.

Jane Harris, who has aligned herself with gender-critical feminism, exemplifies a logic of selective solidarity: one that embraces diversity as narrative material, but withdraws empathy the moment identity becomes embodied, political, and non-metaphorical.

Tweet

The British Comedy of Borders: Amanda Craig and the Stereotype as Structure

Amanda Craig’s The Three Graces, widely praised by literary peers as “witty,” “brilliant,” and “observant,” follows three elderly British women in Tuscany as they reckon with aging, migration, and the spectre of foreignness. The novel has been lauded for engaging contemporary issues—but engagement, here, functions as aesthetic seasoning.

The migrant character is not a subject but a device. The Italians are rendered with exaggerated accents and mannerisms—especially in the audiobook, where the performance borders on the cartoonish. The village exists not as a real place but as a stage set: Tuscany reduced to backdrop, the migrant to threat, the foreign to caricature.

Amanda Craig, a longtime children’s books critic for The Times, has publicly aligned herself with gender-critical feminism. She blocked me on social media after I disagreed with her views—an act of silencing that mirrors her politics of containment. Her feminism operates through literary gatekeeping: it polices who belongs, who speaks, and who is permitted to count as “woman.”

Amanda Craig, a children’s books critic for The Times, has publicly aligned herself with gender-critical feminism. Her feminism operates through literary gatekeeping: it polices who belongs, who speaks, and who is permitted to count as “woman”. She blocked me for pointing out that.

Tweet

The Phelan Legacy: Performance Theory and the Erasure of Embodied Identity

The suspicion toward transsexuals in British feminist circles is not merely rhetorical—it has academic lineage. In Unmarked: The Politics of Performance, Peggy Phelan famously warned that “visibility is a trap,” arguing that attempts to make the marginal visible often result in their commodification, fetishisation, or erasure.

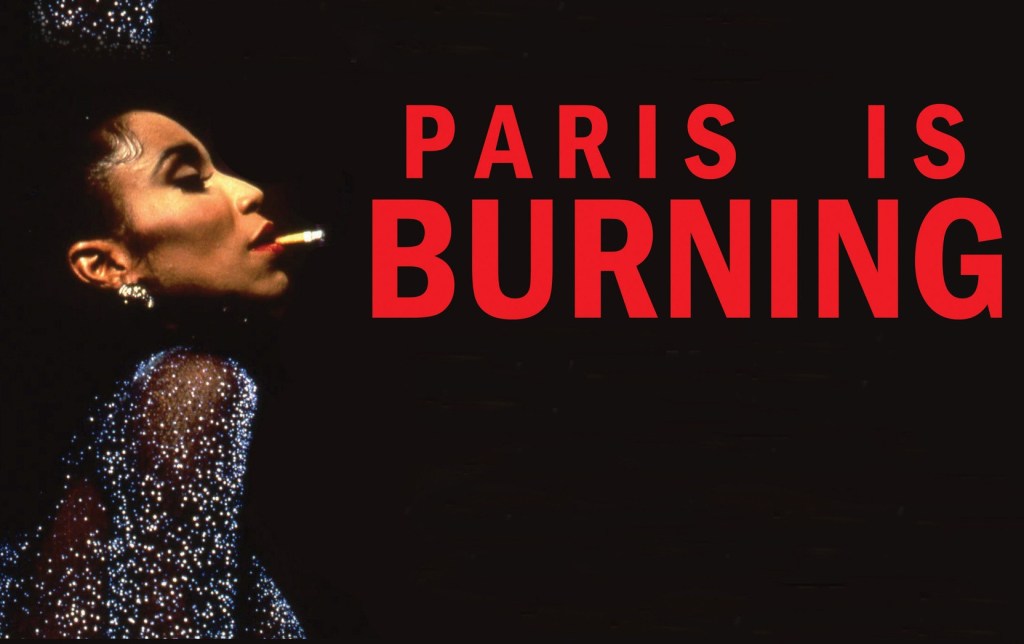

In her reading of Paris Is Burning, Phelan critiques the drag performers’ desire to “pass” as reinforcing dominant gender norms. This argument has since been extended to transsexual women, whose medical transitions are seen by some feminists not as agency, but as aesthetic mimicry. What is liberation for the drag queen becomes complicity for the transsexual.

Scholars such as Viviane Namaste and Julia Serano have forcefully challenged this framework. Namaste critiques the “celebration of invisibility” within queer theory, arguing that for trans people, visibility is not luxury—it is survival. Serano unpacks how the trope of the “deceptive trans woman” emerges precisely when visibility and legibility collapse.

Phelan’s aesthetics of disappearance may sound radical in theory, but applied to trans lives, they become the alibi for cultural erasure.

A Nation That Laughs at Gender and Loathes Its Embodiment

In England, the figure of the cross-dresser—especially in pantomime or comedy—is a familiar and tolerable form of gender disruption. It is marked, theatrical, ironic. What it is not, is embodied. British culture permits gender play so long as it remains temporary and clearly designated as performance.

Transsexuality, by contrast, insists on embodiment. It refuses the wink. It demands to be taken seriously—not as metaphor, but as lived identity. And it is precisely this insistence that provokes discomfort, especially within liberal feminism, which has built its credibility on appropriating otherness in fiction while rejecting it in reality.

In Britain, with J.K. Rowling and other white privileged women in places of power, the discussion was, unsurprisingly, displaced to the realm of property—or more precisely, to space: who belongs, who is out of place, who takes up too much room. In darker historical terms: Lebensraum. Womanhood has become a protected category not just in law, but in real estate.

In Britain, with J.K. Rowling and other white privileged women in places of power, the discussion was, unsurprisingly, displaced to the realm of property—or more precisely, to space: who belongs, who is out of place, who takes up too much room.

Tweet

The Curatorial Logic of British Liberal Feminism

Liberal feminism in Britain today is not a movement of liberation. It is a curatorial apparatus—one that selects the right kinds of difference to exhibit and discards the rest. It speaks inclusion while enacting exclusion. It celebrates the subaltern only when she is fictional. It uplifts the migrant only when he dies offstage. It loves queerness only when it is manageable. And it loathes the transsexual—precisely because she refuses to vanish.

This is the logic behind the Supreme Court’s ruling: not an anomaly, but the cultural expression of a broader managerial strategy. Not a backlash—but infrastructure. Trans women are not new. They are not theory. They are not metaphor. They are not going away.

And yet: the question remains. With both the U.S. and Argentina entering a new dictatorial era grounded in the criminalisation of sexual minorities, is it coincidence—or design—that white British liberal women, comfortably seated within the literary establishment, have chosen this moment to declare war on the transsexual?

And yet: the question remains. With both the U.S. and Argentina entering a new dictatorial era grounded in the criminalisation of sexual minorities, is this the right moment to declare war on the transsexual?

Tweet

Deja una respuesta