The translation in English at the bottom of this post

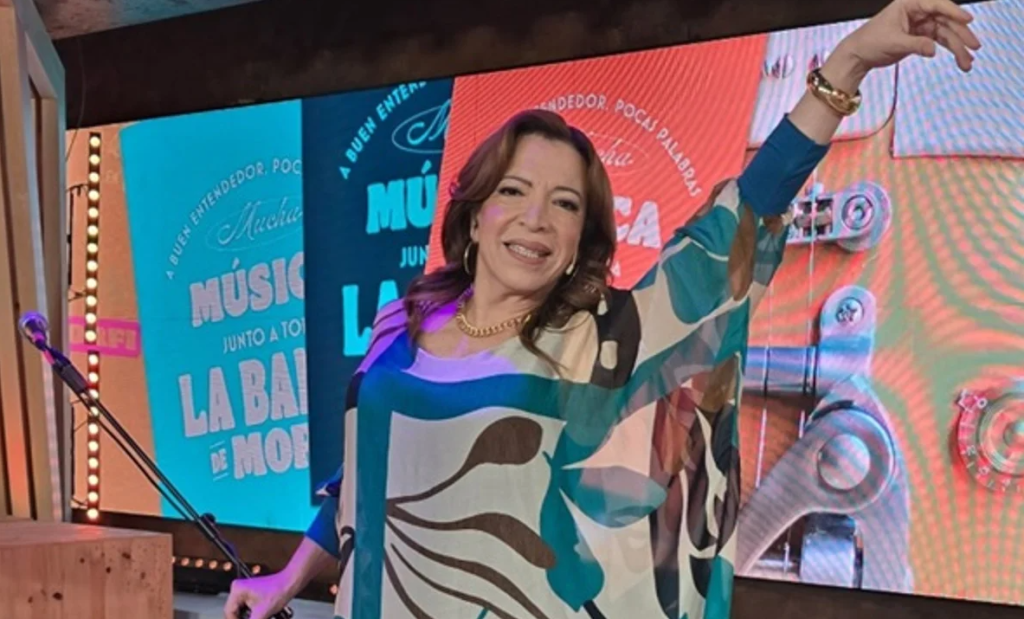

Lizy Tagliani: El lugar imposible de la mujer trans que logra pertenecer

En enero de 2025, Viviana Canosa, desde su programa de televisión abierta, acusó sin pruebas a Lizy Tagliani de estar vinculada a redes de trata y abuso infantil. Lo hizo en horario central, con tono grave y certeza performativa, como si estuviera revelando una verdad incómoda y oculta. El ataque no fue casual: apuntó a una de las figuras más queridas y visibles de la televisión argentina, una mujer trans que, lejos de representar una amenaza, encarna para muchos una forma de ternura y cercanía. El crimen, para Canosa, no fue un acto: fue una identidad. Canosa representa lo opuesto.

El ataque de Viviana Canosa no fue casual: apuntó a una de las figuras más queridas y visibles de la televisión argentina, una mujer trans que, lejos de representar una amenaza, encarna una forma de ternura.

Tweet

Lo que estaba en juego en esa acusación no era una denuncia judicial, sino una operación simbólica: expulsar a Lizy del lugar de pertenencia que había ganado dentro del imaginario afectivo nacional. La cuestión era política o bien como parte de la agenda cultural del gobierno o surgió del clima generado por este gobierno y propiciado por la era de las políticas de identidad que la precedieron. Tagliani se transformó en enemigo por haber sido aceptada, por haber pasado de “marginal” a “entrañable”. Canosa no atacó una fragilidad: castigó un éxito pero un éxito muy particular.

En Inglaterra, la concepción biologicista acaba de imponerse tras que la autora de Harry Potter y otras autoras como Jane Harris y Amanda Craig insistieran durante casi una década en que se es mujer por tener vagina. En Inglaterra, el establishment de la literatura transformó esto en una especie de casta (como la cultura que la contiene). Ese feminismo liberal, que en la Argentina representaría Viviana Canosa es una trinchera desde la cual vigilar, excluir y corregir cualquier disidencia que no se ajuste a su concepción esencialista de la feminidad es mandato. Lo hacen desde el ‘prestigio’, desde la palabra publicada, desde los círculos literarios o mediáticos (en el caso argentino) que se presentan como inclusivos mientras restringen la voz de quienes no nacieron con la marca biológica correcta.

El feminismo liberal/libertario, que en la Argentina representaría Viviana Canosa es una trinchera desde la cual vigilar, excluir y corregir cualquier disidencia que no se ajuste a su concepción esencialista de la feminidad. Lo hacen desde el ‘prestigio’, desde la palabra publicada o mediática (en el caso argentino).

Tweet

La decisión reciente del Tribunal Supremo británico de negar a las mujeres trans el reconocimiento legal de su condición de mujeres marca un hito regresivo en un clima cultural profundamente reactivo, de vigilancia, criminizalizacion y silenciamiento.

Harris, por ejemplo, ha sido celebrada por su novela Sugar Money, en la que adopta la voz en primera persona de un esclavizado en el siglo XVIII. A pesar de recibir elogios de la crítica británica—entre ellos, del Guardian y de The Sunday Times—la novela fue objeto de fuertes críticas por parte de intelectuales afrocaribeños, que denunciaron el gesto como un acto de apropiación narrativa encubierto en corrección política. Alguien que escribe desde la voz de un esclavo no puede luego cerrar filas contra mujeres trans sin revelar las fisuras estructurales de su ética escritural.

Amanda Craig, por su parte, publicó The Three Graces, una novela celebrada por su supuesta agudeza al retratar la vejez femenina, pero que no solo reproduce clichés sobre los italianos como sujetos inferiores o temperamentales, sino que ha tomado posición abiertamente en contra del reconocimiento de las mujeres trans como mujeres. Craig, crítica literaria y figura del círculo de escritoras del Times, bloquea, cancela y ridiculiza a quienes disienten de su visión esencialista de la feminidad, al tiempo que recibe elogios por su supuesta defensa de la diversidad. Su literatura, como su política, está atravesada por un humanismo decorativo que margina bajo la forma de la cortesía.

Amanda Craig, crítica literaria y figura del círculo de escritoras del Times, bloquea, cancela y ridiculiza a quienes disienten de su visión esencialista de la feminidad, al tiempo que recibe elogios por su supuesta defensa de la diversidad

Tweet

La violencia simbólica que estas autoras ejercen tiene una genealogía más profunda y el problema radica en lo performativo no del genero sino de quien es el que designa qué. Quién tiene el poder de nombrar? Como plantea Peggy Phelan en su lectura de Paris Is Burning, toda identidad es performativa, toda categoría es citacional. Pero cuando la performance se vuelve demasiado efectiva, demasiado deseable o demasiado visible, sobreviene el castigo. Lo que molesta no es el “exceso” sino el éxito de la performance. Y ese es el caso de Lizy Tagliani.

Lo que molesta no es el “exceso” sino el éxito de la performance. Y ese es el caso de Lizy Tagliani.

Tweet

Cuando Canosa la acusa, no está atacando una performance frágil: está castigando el hecho de que Lizy haya logrado ser percibida socialmente como una mujer legítima, visible y querida. O, mejor dicho, como dicen en teatro, Lizy logró ‘suspender el descreimiento’. Ese es su “éxito”: haber alcanzado una forma de “realness” femenina dentro del imaginario popular argentino, desde un lugar disidente pero afectivamente admitido. Esa contradicción es, hoy, intolerable en la Trumpiana argentina. De todos modos, le comunico a Canosa que está del lado equivocado de la historia.

Conductora, humorista, anfitriona televisiva y mediadora emocional, Lizy logró inscribirse en el campo simbólico de lo familiar y lo respetable sin ocultar su identidad de mujer trans ni hacer tantas concesiones como Flor de la V que tuvo que escenificar un abrazo de la Iglesia Católica que tanto daño hizo a su propio colectivo o tener ‘in vitro’ hijos arios, negando sus raíces ‘marrones’. El precio pagado por Flor de la V es su desaparición como lo que era. La suya no fue una performance de ‘realness’ sino una ‘autoinmolación’.. Y eso, para ciertos sectores del periodismo y de la televisión—históricamente misóginos y transfóbicos—es el precio que debía pagar. Lizy Tagliani apareció en otro momento y manejo al publico con otro carisma. Mientras Flor de la V siempre fue vista como una usurpadora asimilada, en Tagliani hay algo disidente.

Lizy Tagliani logró inscribirse en el campo simbólico de lo familiar y lo respetable sin ocultar su identidad de mujer trans ni hacer tantas concesiones como Flor de la V.

Tweet

El rechazo de Canosa (Rawling, Harris y Craig) hacia las mujeres trans no se limita a una postura “biologicista” sobre el sexo: en el fondo, es una defensa del privilegio de nombrar y de escribir sobre el mundo sin que ese acto sea interrogado. Es una defensa del nombre propio, de la autoridad escritural, del lugar de enunciación protegido. Lo de Canosa fue burdo y seguramente protegido judicialmente y estatalmente porque no puede ser tan idiota ya que lo que se le puede venir es un juicio por daños que debería dejarla en la calle. El caso de Jane Harris como Amanda Craig en UK es más sutil y estructural: escriben sobre otras identidades desde una posición de supuesto universalismo blanco y femenino, sin problematizar su propia implicación en las relaciones de poder que estructuran la representación. Neo-colonalizan.

El rechazo de Canosa (Rawling, Harris y Craig) hacia las mujeres trans no se limita a una postura “biologicista” sobre el sexo: en el fondo, es una defensa del privilegio de nombrar y de escribir sobre el mundo sin que ese acto sea interrogado.

Tweet

Es el mismo gesto que critican bell hooks y Jackie Goldsby en Paris Is Burning: Jennie Livingston, como directora blanca, filma una cultura queer racializada desde afuera, sin implicarse subjetivamente. Del mismo modo, Harris y Craig se benefician del acto de apropiación —ya sea adoptando la voz de una mujer esclavizada (en el caso de Harris) o reproduciendo estereotipos racistas sobre italianos (como hace Craig en The Three Graces)— pero sin abrir ese acto a una crítica del lugar desde el cual escriben. Representan sin exponerse. Nombran sin ser nombradas. Los programas de panelistas en la Argentina usan el condicional o tratan de dar un golpe de efecto para lograr atención y rating pero, en el camino, se involucran en un debate que las supera. Canosa incluso intentó la estrategia de hacerse la ofendida.

Por eso les incomodan las mujeres trans que escriben, opinan o intervienen públicamente: porque no son objetos de representación, sino sujetos de discurso. Porque desestabilizan esa división entre quien tiene el derecho a hablar (ellas) y quien debe ser narrado. La mujer trans que escribe o que es amada por el publico no es la caricatura que ellas quieren que sea: es competencia real.

The Trans Woman Who Pleases Too Much: The Impossible Place of the Accepted Trans Woman

In January 2025, Viviana Canosa, during her primetime television program, publicly and baselessly accused Lizy Tagliani of being involved in child abuse and trafficking networks. She did so with grave tone and performative certainty, as if revealing some uncomfortable and hidden truth. The attack was far from accidental: it targeted one of the most beloved and visible figures of Argentine television, a trans woman who, far from posing any threat, represents for many a source of tenderness and warmth. The crime, for Canosa, was not an act—it was an identity. Canosa stands for the opposite of everything Lizy embodies.

This was not a legal accusation—it was a symbolic operation: to expel Lizy from the space of belonging she had earned in the national affective imagination. The attack was either part of the government’s broader cultural agenda or a symptom of the climate it fostered, built on years of identity politics. Tagliani became an enemy not for what she did, but for what she had achieved: she had been accepted, moving from “marginal” to “beloved.” Canosa didn’t attack a weakness—she punished a very specific kind of success.

In England, the biologicist conception of womanhood has just triumphed, after years of public insistence from the author of Harry Potter and others—such as Jane Harris and Amanda Craig—that “being a woman” depends on having a vagina

Tweet

In England, the biologicist conception of womanhood has just triumphed, after years of public insistence from the author of Harry Potter and others—such as Jane Harris and Amanda Craig—that “being a woman” depends on having a vagina. In the UK, the literary establishment has transformed this discourse into a sort of caste system—mirroring the culture that upholds it. This form of liberal feminism, which in Argentina is embodied by figures like Canosa, has become a trench from which to monitor, exclude, and correct any dissent that refuses to fit into their essentialist understanding of womanhood. They speak from prestige, from publication, from literary or media circles (in Argentina’s case), which present themselves as inclusive while systematically restricting the voices of those not born with the “correct” biological mark.

This form of liberal feminism speaks from prestige presented as inclusive while restricting the voices of those not born with the “correct” biological mark.

Tweet

The recent ruling by the UK Supreme Court denying legal recognition to trans women as women represents a major regression in a cultural climate marked by surveillance, criminalization, and silencing.

Jane Harris, for instance, has been widely praised for her novel Sugar Money, written from the first-person perspective of an enslaved man in the 18th century. Though lauded by British critics—including The Guardian and The Sunday Times—the book faced harsh criticism from Afro-Caribbean intellectuals, who saw it as a politically correct but ultimately appropriative narrative gesture. A writer who speaks in the voice of a slave cannot, without contradiction, turn around and exclude trans women without revealing the structural fissures of her ethical posture.

Amanda Craig, meanwhile, published The Three Graces, a novel celebrated for its supposed insight into aging women, but which reproduces stereotypes of Italians as inferior or overly emotional. She has openly opposed recognizing trans women as women. A literary critic and prominent figure in the Times’ circle of writers, Craig blocks, cancels, and ridicules those who challenge her essentialist views on femininity—while continuing to be praised for her supposed commitment to diversity. Her literature, like her politics, is grounded in a decorative humanism that excludes under the guise of civility.

The symbolic violence these authors exert has a deeper genealogy. The real issue is not gender as performance, but who holds the power to designate, to name. As Peggy Phelan argues in her reading of Paris Is Burning, all identity is performative, all categories are citational. But when a performance becomes too effective, too desirable, too visible—it is punished. What troubles these figures is not excess, but the success of the performance. And that is Lizy Tagliani’s case.

As Peggy Phelan argues in her reading of Paris Is Burning, all identity is performative, all categories are citational. But when a performance becomes too effective, too desirable, too visible—it is punished.

Tweet

When Canosa accuses her, she is not targeting a fragile performance—she is punishing the fact that Lizy has been socially perceived as a legitimate, visible, and beloved woman. Or, to use a theatre expression, Lizy succeeded in “suspending disbelief.” That is her success: achieving a form of feminine realness within the popular Argentine imagination, from a dissonant but affectively accepted position. That contradiction is intolerable in Milei’s Trumpian Argentina. Still, one might tell Canosa: you are on the wrong side of history.

As a host, comedian, television personality, and emotional anchor, Lizy earned a place in the symbolic sphere of respectability and familiarity—without hiding her trans identity or making the kind of concessions that Flor de la V had to, such as embracing the Catholic Church that has historically harmed her community, or having “in vitro” Aryan children to negate her own marrón roots. The price Flor paid was to disappear as who she was. Hers was not a performance of realness but an auto-immolation. And for many in Argentine media and journalism—long steeped in misogyny and transphobia—that was the price to pay. Lizy, by contrast, appeared in a different moment and managed the public with a different charisma. While Flor de la V was always seen as an assimilated usurper, Lizy retained something radically dissident.

The rejection of Canosa (like Rowling, Harris, and Craig) toward trans women is not just about “biological sex.” At its core, it is a defense of the power to name, of the authority to write the world without being questioned. It is a defense of the proper name, of scriptural authority, of an unchallenged place of enunciation. Canosa’s attack was crude—likely protected by legal and state systems—and suggests a level of impunity. She cannot possibly be that foolish. What she may be, though, is legally vulnerable: a civil lawsuit for damages could easily leave her destitute. The cases of Harris and Craig in the UK are more subtle, more structural: they write about other identities from a supposed universalist white and female position, without ever examining their own implication in the power relations that structure representation. They neo-

Jane Harris and Amanda Craig in the UK write about other identities from a supposed universalist white and female position, without ever examining their own implication in the power relations that structure representation. They neo-colonize.

Tweet

This is the same gesture that bell hooks and Jackie Goldsby critique in Paris Is Burning: Jennie Livingston, a white director, films a racialized queer culture from the outside, without implicating herself. In the same way, Harris and Craig benefit from acts of appropriation—whether it’s writing in the voice of an enslaved woman (Harris) or reproducing racial stereotypes of Italians (Craig)—but never open their work to a critique of their own positionality. They represent without exposing themselves. They name without being named.

Panel shows in Argentina operate in a similar fashion: they use the conditional voice, throw explosive claims to grab attention and ratings, and in doing so entangle themselves in debates they do not fully grasp. Canosa even tried the classic strategy of playing the offended victim.

This is why trans women who write, speak, and intervene publicly are so troubling to them: because they are not objects of representation, but subjects of discourse. They disrupt the division between those who have the right to speak (like Canosa, Harris, Craig) and those who are only supposed to be narrated. The trans woman who writes—or who is beloved by the public—is not the caricature they wish her to be: she is real competition.

Deja una respuesta