Scroll Down to the Bottom of this Post to See the English Version

Su Testamento Silencioso: La Tumba de Francisco en Santa María Maggiore

Todo gesto del Papa Francisco ‘es’ profundamente político: no se trata de dejar de ser Papa, sino de habitar ese rol con otra sensibilidad. Hasta el final o, mejor dicho, desde la tumba.

Tweet

El Papa argentino fue siempre devoto de la Virgen. La figura de María, en la espiritualidad franciscana, no es sólo la madre de Dios: es la madre del pueblo, la que intercede, la que acoge. Francisco visitó Santa María Maggiore al comienzo y al final de cada viaje papal. Ahora, su cuerpo quedará allí, entre mosaicos antiguos y oraciones anónimas. Muy cerca del consulado argentino en Roma, como si incluso en su muerte su historia personal y su país de origen volvieran a rozarse, sin solemnidad pero con firmeza.

A diferencia de los monumentos de mármol y bronce, esta tumba no busca la eternidad sino la humildad. Y sin embargo, como todo gesto de Francisco, es profundamente político: no se trata de renunciar al poder, sino de desplazar su signo. No se trata de dejar de ser Papa, sino de habitar ese rol con otra sensibilidad. Hasta el final o, mejor dicho, desde la tumba.

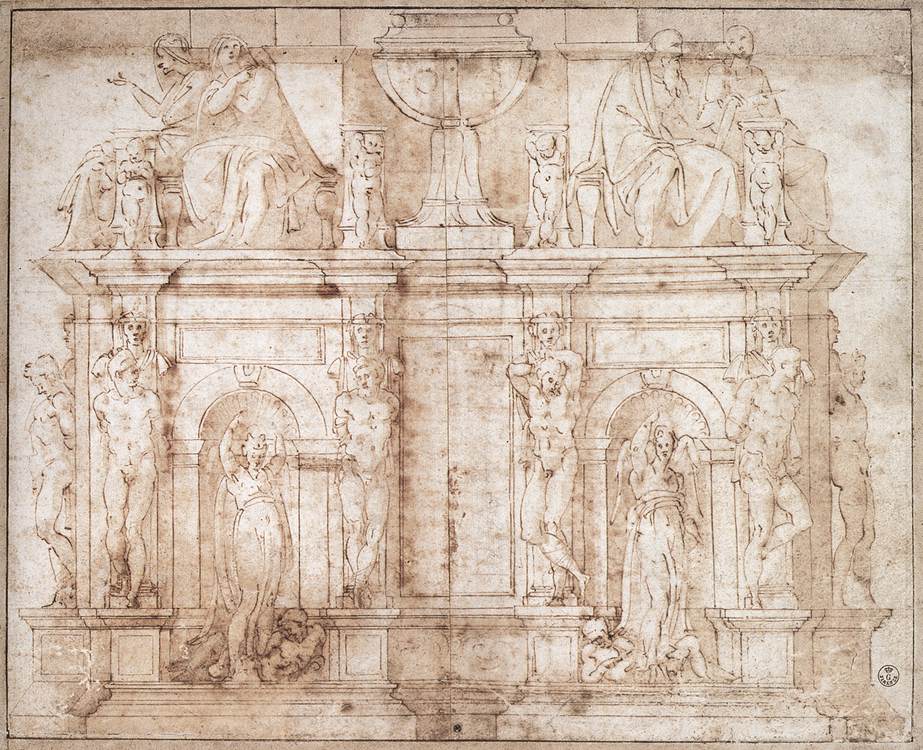

Las tumbas de los papas siempre hablaron. Fueron, durante siglos, declaraciones de poder, fe y arte. Algunas se quedaron en el papel, como la monumental tumba frustrada que Miguel Ángel proyectó para Julio II—una estructura colosal con más de cuarenta figuras—pensada para colocarse donde hoy se alza el altar mayor, es decir, la Cathedra Petri. Los papas deben ocuparse de su tumba en vida, ya que son pocos los sucesores que desean perpetuar la gloria de quien vino antes, menos aún si esa gloria viene con la carga simbólica de la muerte, que muchas veces, como schadenfreude, paraliza la continuidad.

Esto lo entendió bien Urbano VIII, quien encargó a Gian Lorenzo Bernini su propia tumba: una maravilla del bel composto cuyo tema es la fugacidad de la vida, al menos en esta tierra. En Roma, donde los cuerpos se convierten en arquitectura, la arquitectura en arte y el arte en gloria, enterrar a un Papa es también una forma de canonizar un mensaje. Hoy, la relación entre arte y religión—sobre todo en el caso del catolicismo—está rota. Francisco lo sabía.

Ser enterrado en la basílica de Santa María Maggiore puede ser leído como un acto de modestia pero eso sería insultar la inteligencia de Francisco. Fundada en el siglo IV está saturado de implicancias.

Tweet

El Papa argentino eligió, en cambio, el gesto más simple y más radical: ser enterrado en la basílica de Santa María Maggiore. Una elección, aparentemente modesta, saturada de implicancias. Santa María Maggiore no es sólo una de las cuatro basílicas mayores de Roma y uno de los siete templos del recorrido de peregrinación; es, tal vez, la más íntima. Fundada en el siglo IV, bajo el influjo de una visión mariana y una nevada milagrosa, fue una de las primeras iglesias dedicadas a la Virgen.

El Cristo Transexual Anti-Alt+Right

Santa María Maggiore representa un cristianismo anterior a su transformación en lo que hoy podríamos llamar—en términos actuales—un cristianismo ‘‘trumpiano’. Incluso con su muerte, el silencio de Francisco opera políticamente.

Tweet

Su historia es, en muchos sentidos, la historia del cristianismo popular: un cristianismo de maternidades, de cuerpos transexuales (o polimórficos), de futuros contactos más profundos que los oficialmente reconocidos con las “colonias”. Lo más importante, para mi argumento, es que Santa María Maggiore representa un cristianismo anterior a su transformación en lo que hoy podríamos llamar—en términos actuales—un cristianismo trumpiano. Incluso con su muerte, el silencio de Francisco habla.

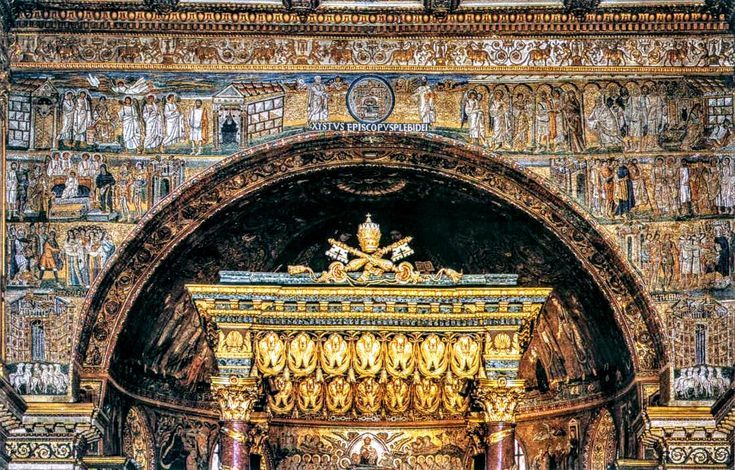

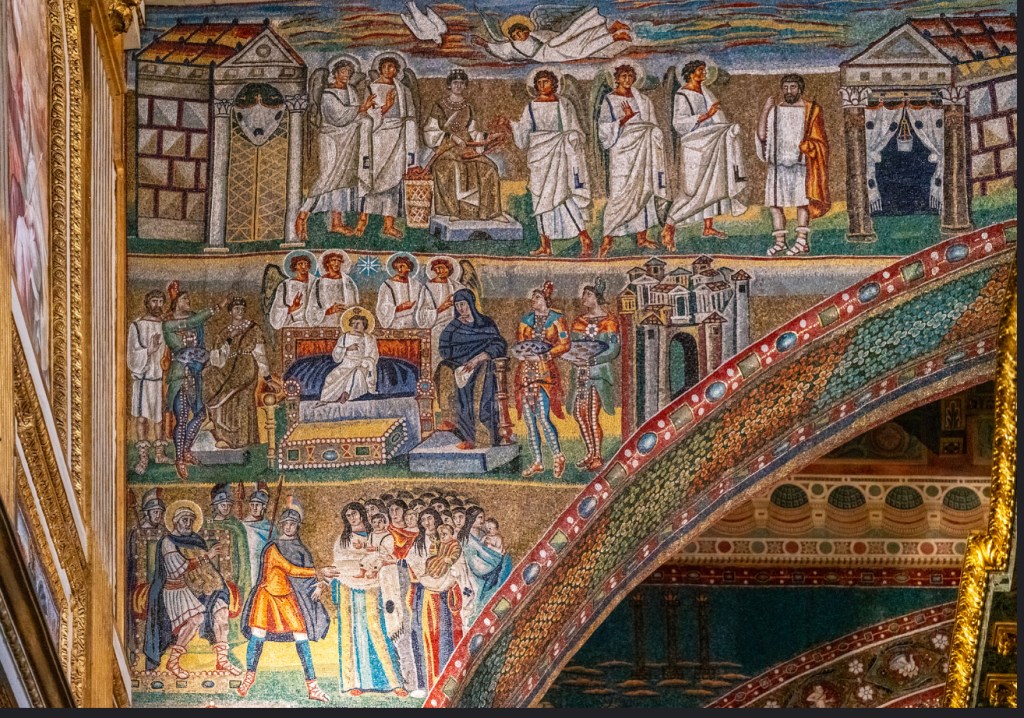

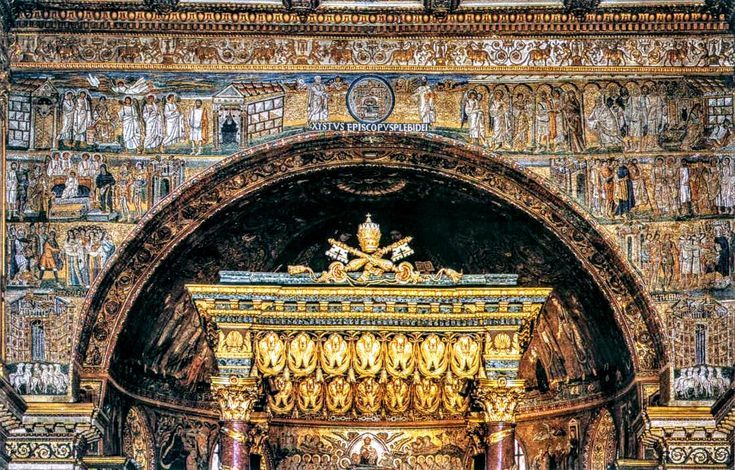

En el ábside de Santa María Maggiore se conserva uno de los conjuntos de mosaicos más antiguos del cristianismo romano. Ejecutados en el siglo V por encargo del papa Sixto III, celebran el Concilio de Éfeso (431), que confirmó la maternidad divina de María (Theotokos) frente a la herejía nestoriana. El Cristo que aparece entronizado no es, como suele pensarse, una imagen arriana, pero sí conserva huellas de un momento de indecisión iconográfica y teológica en que la figura de Jesús no había sido del todo absorbida por la lógica imperial del Pantocrátor bizantino. Cristo como Zeus. El dios macho, brutal, condenatorio, que Francisco, evidentemente, con ternura, rechaza.

Haciéndose enterrar en Santa María Maggiore, Francisco elige la caricia de María en lugar de la piedra de San Pedro o el club de gentlemen de San Pablo.,

Tweet

Una de las imágenes más radicales de ese Cristo no-patriarcal aparece en el mosaico del baptisterio arriano de Rávena, construido a fines del siglo V bajo dominio ostrogodo. Allí, en la cúpula, se representa el bautismo de Cristo en el Jordán, pero con una figura que rompe por completo con las convenciones visuales que siglos más tarde se volverán norma. Cristo aparece joven, imberbe, desnudo, con un cuerpo estilizado, casi lánguido. Sus formas no son varoniles, sino ambiguas: más cercanas a la androginia que al virilismo. Su postura no es de autoridad, sino de entrega. Y las aguas del Jordán lo envuelven como una segunda piel, con un trazo ondulante que roza lo sensual. Un Cristo fluido. Un cuerpo sagrado sin masculinidad militante.

Francisco en su tumba nos invita a volver al Cristo Transexual de Sant’Appolinare en Classe (baptisterio): polimorfo, metamórfico, sensual, frágil, humano, para todos.

Tweet

Insisto: es tan importante el gesto de Francisco de repensar los orígenes del cristianismo desde ese lugar, porque son esas las preguntas que, en vida pero también desde la muerte, el querido Papa argentino parece estar formulando.

Este Cristo, que algunos estudiosos han calificado como “casi transexual” por su ambigüedad formal y su desmarque de la anatomía masculina heroica, ofrece una alternativa teológica y estética a la imagen del Salvador-juez. Lo que aparece allí no es un dios militarizado, sino un cuerpo vulnerable, dispuesto, suave. Un dios-epifanía, no un dios-cetro.

Basilica de San Pedro: Club de Machos

Cuando Francisco elige ser enterrado bajo la mirada del Cristo joven de Santa María Maggiore, sintoniza con esa iconografía desviada. No lo hace como un gesto deliberadamente queer, pero sí como una forma de desandar el camino del autoritarismo masculinista. De salirse del canon de la dominación visual. Es, si se quiere, un regreso a la incertidumbre de las primeras imágenes. Un Papa que muere bajo la mirada de un Cristo aún sin barba, aún sin imperio, aún sin cruz.

Desde ese lugar, le habla—en su muerte—a los nuevos emperadores del presente: a los dogmáticos del capital, a los teólogos del control, a los restauradores del orden. Y lo hace sin palabras, sólo con su cuerpo. Elige descansar bajo la mirada de un Cristo que no fiscaliza, que no administra el infierno. Un Cristo que se parece, apenas, a un joven sentado que observa. O a una cruz sin carne, sin género, sin mandato. Y esa imagen, en tiempos de vigilancia moral y restauraciones de la virilidad, vale más que mil encíclicas.

Santa María Maggiore fue construida sobre el Esquilino, una de las siete colinas de Roma, en el sitio donde, según la leyenda, en la madrugada del 5 de agosto del año 358, la Virgen se le apareció en sueños al Papa Liberio y a un patricio llamado Juan. Les pidió que construyeran una iglesia donde al día siguiente caería nieve. Y así fue: una nevada milagrosa cubrió la colina en pleno verano. El contorno de la basílica fue trazado en la nieve misma. Así nació una iglesia que no surgió del poder imperial, sino de un sueño y una maternidad.

Cristo como Zeus es el dios macho, brutal, condenatorio, que Francisco, evidentemente, con ternura, rechaza al evitar descansar en el Vaticano donde ni siquiera quiso vivir.

Tweet

Ese origen marcó no sólo su carácter afectivo, sino su vocación popular. Santa María Maggiore no es una iglesia de conquista, sino de consuelo. No de mártires, sino de madres. Esa figura mariana protectora tuvo un desarrollo decisivo en la espiritualidad franciscana desde el siglo XIII. Para San Francisco de Asís, María no era sólo la madre de Cristo, sino la imagen perfecta de la pobreza, la humildad y la misericordia.

La Madre y el primer Papa Latinoaméricano

Pero ese amor mariano también devino batalla. En Sevilla, entre los siglos XV y XVI, los franciscanos sostuvieron una gran contienda doctrinal contra los dominicos: la defensa del dogma de la Inmaculada Concepción—la idea de que María fue concebida sin pecado original. Para los franciscanos, esa pureza no era lujo teológico, sino núcleo de su fe afectiva. Esta disputa se expresó en procesiones, imágenes, cultos populares, y también en la colonización.

En América Latina, donde franciscanos y jesuitas jugaron un papel central en la evangelización, la figura de la Virgen Inmaculada se convirtió en un puente entre el catolicismo y los imaginarios indígenas: María se acercó a la Pachamama. No imponía, abrazaba. No juzgaba, cuidaba. En sus múltiples advocaciones—del cerro, del valle, de los milagros—la Virgen fue el rostro amable de una religión que llegaba, por otras vías, con violencia. La Guadalupana, la Virgen de Málaga, la Virgen de los Dolores. Todas ellas son también reflejo de esa tensión.

En América Latina, donde franciscanos y jesuitas jugaron un papel central en la evangelización, la figura de la Virgen Inmaculada se convirtió en un puente entre el catolicismo y los imaginarios indígenas: María se acercó a la Pachamama.

Tweet

Que Francisco elija ser enterrado en Santa María Maggiore, tan cerca del primer Cristo sin barba y de la Virgen que lo custodia, no es un gesto neutro. Es una toma de posición teológica, política y estética. No quiere ser recordado como Pedro, mártir de piedra, ni como Pablo, arquitecto de la doctrina. Francisco es el Papa de la compasión y la ternura, el que entendió que no hay Iglesia sin esos principios básicos de lo humano.

Ese gesto final—el de elegir su tumba—vale más que muchas de sus encíclicas, homilías y entrevistas. Porque en esa elección sin palabras, Francisco nos deja su testamento visual y espiritual: un modo de estar, incluso en la muerte.

© Rodrigo Cañete, 2025. Todos los derechos reservados, incluso los que no me reconocerían si este texto fuera dicho desde el púlpito. Citas breves con crédito, sí. Copia sin pensar, no.

Francis Operating from the Beyond—Not Beneath Peter, but Beneath the Mother

The Argentine Pope was always devoted to the Virgin. In Franciscan spirituality, the figure of Mary is not only the mother of God, but the mother of the people: the one who intercedes, the one who embraces. Francis visited Santa Maria Maggiore at the beginning and end of every papal journey. Now, his body will rest there, among ancient mosaics and anonymous prayers. Very close to the Argentine consulate in Rome, as if even in death his personal story and his country of origin once again brushed against each other—not with solemnity, but with firmness.

Unlike the marble and bronze monuments, this tomb does not seek eternity, but humility. And yet, like every gesture of Francis, it is deeply political: it’s not about renouncing power, but about displacing its sign. Not about ceasing to be Pope, but about inhabiting that role with a different sensitivity. Until the very end.

Like every gesture of Pope Francis, it is deeply political: it’s not about renouncing power, but about displacing its sign. Not about ceasing to be Pope, but about inhabiting that role with a different sensitivity. Haunting his succesors.

Tweet

The tombs of Popes have always spoken. For centuries, they have been declarations of power, faith, and art. Some never materialized, like Michelangelo’s monumental but frustrated tomb project for Julius II—a colossal structure with over forty figures, designed to be placed where the high altar now stands, namely the Cathedra Petri. Popes must attend to their tombs during their lifetimes, as few successors wish to glorify their predecessors—especially if that glory comes with the symbolic burden of death, which often, as schadenfreude, paralyzes continuity.

Urban VIII understood this well when he commissioned Gian Lorenzo Bernini to design his own tomb: a marvel of bel composto whose theme is the fleetingness of life—at least on this earth. In Rome, where bodies become architecture, architecture becomes art, and art becomes glory, burying a Pope is also a way of canonizing a message. Today, the relationship between art and religion—especially Catholicism—is broken. Francis knew this.

Instead, the Argentine Pope chose the simplest and most radical gesture: to be buried in the Basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore. A seemingly modest choice, but one saturated with implications. Santa Maria Maggiore is not only one of the four major basilicas of Rome and one of the seven pilgrimage churches; it is perhaps the most intimate. Founded in the fourth century, under the influence of a Marian vision and a miraculous snowfall, it was one of the first churches dedicated to the Virgin.

Its history is, in many ways, the history of popular Christianity: a Christianity of maternities, of transsexual (or polymorphic) bodies, of deeper future connections than those officially recognized with the “colonies.” Most importantly, for my argument, Santa Maria Maggiore represents a form of Christianity that existed before it was transformed into what we might today call—speaking in current terms—Trumpian Christianity. Even in death, the silence of Francis speaks.

By choosing to be buried in Santa Maria Maggiore, Francis chooses a form of Christianity that existed before it was transformed into what we might today call a Trumpian Christianity. Even in death, the silence of Francis speaks very loudly.

Tweet

In the apse of Santa Maria Maggiore, one of the oldest mosaics in Roman Christianity is preserved. Executed in the fifth century under Pope Sixtus III, it celebrates the Council of Ephesus (431), which confirmed Mary’s divine motherhood (Theotokos) against the Nestorian heresy. The enthroned Christ depicted here is not, as some assume, an Arian image, but it does preserve traces of an iconographic and theological uncertainty—a time when the figure of Jesus had not yet been fully absorbed by the imperial logic of the Byzantine Pantocrator. Christ as Zeus. The brutal, masculine, condemning god that Francis, with tenderness, evidently rejects.

One of the most radical depictions of that non-patriarchal Christ appears in the mosaic of the Arian Baptistery of Ravenna, built in the late fifth century under Ostrogothic rule. In the dome, Christ’s baptism in the Jordan is shown—but with a figure that completely breaks from the visual conventions that would later become standard. Christ appears young, beardless, naked, with a slender, almost languid body. His forms are not manly, but ambiguous: closer to androgyny than virility. His posture is not one of authority, but of surrender. And the waters of the Jordan envelop him like a second skin, with an undulating trace that verges on the sensual. A fluid Christ. A sacred body without militant masculinity.

Francis avoids the Vatican even in the after-life because he identifies it with a misogynistic Gentlemen’s Club led by Saint Peter and Saint Paul. That is his political battle now. Astonishing legacy.

Tweet

I insist: Francis’s gesture of rethinking the origins of Christianity from that place is crucial, because those are the questions the beloved Argentine Pope seems to be posing—not just in life, but now, in death. This Christ—whom some scholars have described as “almost transsexual” for his formal ambiguity and rejection of heroic male anatomy—offers a theological and aesthetic alternative to the image of the Savior-judge. What we see here is not a militarized god, but a vulnerable, receptive, gentle body. A god-epiphany, not a god-scepter.

By choosing to be buried under the gaze of the youthful Christ at Santa Maria Maggiore, Francis aligns with this subversive iconography. Not as a deliberately queer gesture, but as a way of unlearning masculinist authoritarianism. Of stepping outside the canon of visual domination. It is, if you will, a return to the uncertainty of the first images. A Pope who dies under the gaze of a Christ not yet bearded, not yet imperial, not yet crucified.

By choosing to be buried under the gaze of the youthful Christ at Santa Maria Maggiore, Francis goes back to the transexual Christian iconography. Not as a deliberately queer gesture, but as a way of unlearning masculinist authoritarianism.

Tweet

From that place, he speaks—in death—to today’s new emperors: to the dogmatists of capital, the theologians of control, the restorers of order. And he does so without words, only with his body. He chooses to rest under the gaze of a Christ who does not judge, who does not administer hell. A Christ who resembles, barely, a young man sitting in watchful stillness. Or a cross without flesh, without gender, without command. And that image, in a time of moral surveillance and revivals of virility, is worth more than a thousand encyclicals.

Santa Maria Maggiore was built on the Esquiline Hill, one of the seven hills of Rome, on a site that, before the fourth century, housed patrician villas and likely a pagan temple. According to legend, on the night of August 5, 358, the Virgin appeared in a dream to Pope Liberius and a patrician named John, asking them to build a church where snow would fall the next day. And so it happened: a miraculous snowfall covered the hill in the middle of the Roman summer. The outline of the basilica was traced in the snow itself. Thus was born a church not born of imperial power, but of a dream and a maternity.

That origin marked not only its affective character but also its popular vocation. Santa Maria Maggiore is not a church of conquest, but of consolation. Not of martyrs, but of mothers. This Marian figure as protector had a decisive development in Franciscan spirituality from the thirteenth century onward. For Saint Francis of Assisi, Mary was not only the mother of Christ but the perfect image of poverty, humility, and mercy.

But that Marian devotion also became a battleground. In Seville, between the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, the Franciscans engaged in a major doctrinal dispute against the Dominicans: the defense of the dogma of the Immaculate Conception—the idea that Mary was conceived without original sin. For the Franciscans, this purity was not theological luxury, but the core of their affective faith. This debate found expression in processions, images, popular devotions, and also in colonization.

In Latin America, where Franciscans and Jesuits played a central role in evangelization, the figure of the Immaculate Virgin became a bridge between Catholicism and Indigenous imaginaries: Mary approached the Pachamama. She did not impose, she embraced. She did not judge, she cared. In her many invocations—of the hill, the valley, the miracles—the Virgin was the gentle face of a religion that otherwise arrived with violence. The Guadalupana, the Virgin of Málaga, the Virgin of Sorrows. All of them reflect this tension.

In Latin America, where Franciscans and Jesuits played a central role in evangelization, the figure of the Immaculate Virgin became a bridge between Catholicism and Indigenous imaginaries: Mary approached the Pachamama.

Tweet

That Francis chose to be buried in Santa Maria Maggiore, so near that first beardless Christ and the Virgin who watches over him, is no neutral gesture. It is a theological, political, and aesthetic statement. He does not want to be remembered as Peter, martyr of stone, or as Paul, architect of doctrine. Francis is the Pope of compassion and tenderness, who understood that there is no Church without those basic principles of the human.

That final gesture—the choice of his tomb—speaks louder than many of his encyclicals, homilies, and interviews. Because in that wordless decision, Francis leaves us his visual and spiritual testament: a way of being, even in death.

© Rodrigo Cañete, 2025. All rights reserved—even those that wouldn’t be acknowledged if this were preached from the pulpit. Brief quotations with credit, yes. Mindless copying, no.

Cliqueá para hacerte miembro pago de mi Canal de YouTube y hacer los cursos:

Deja una respuesta