Scroll Down for the English Version

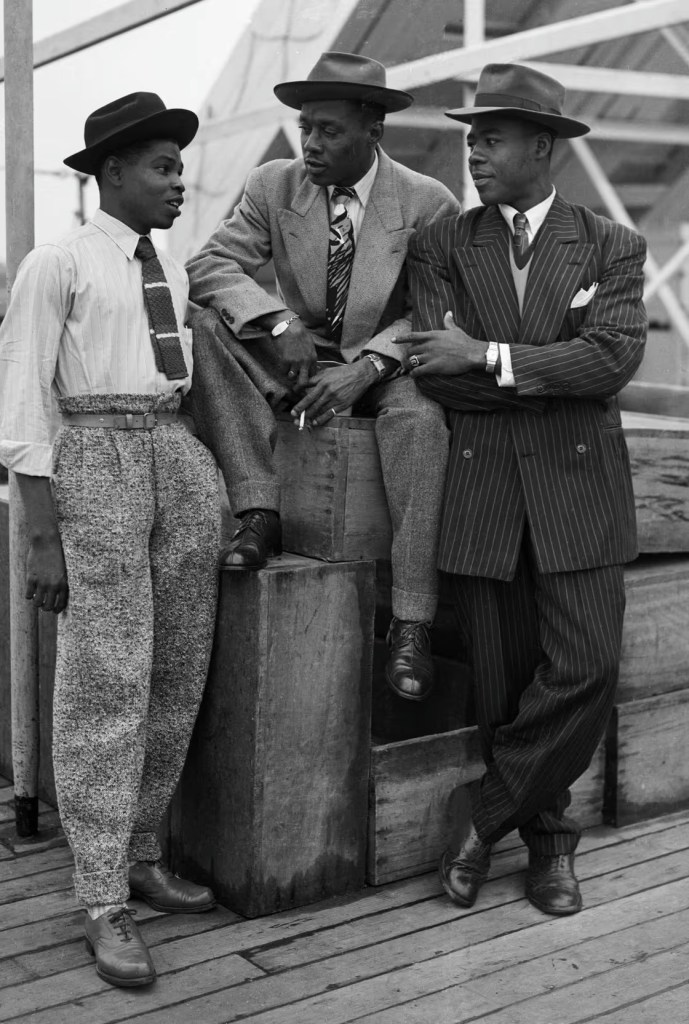

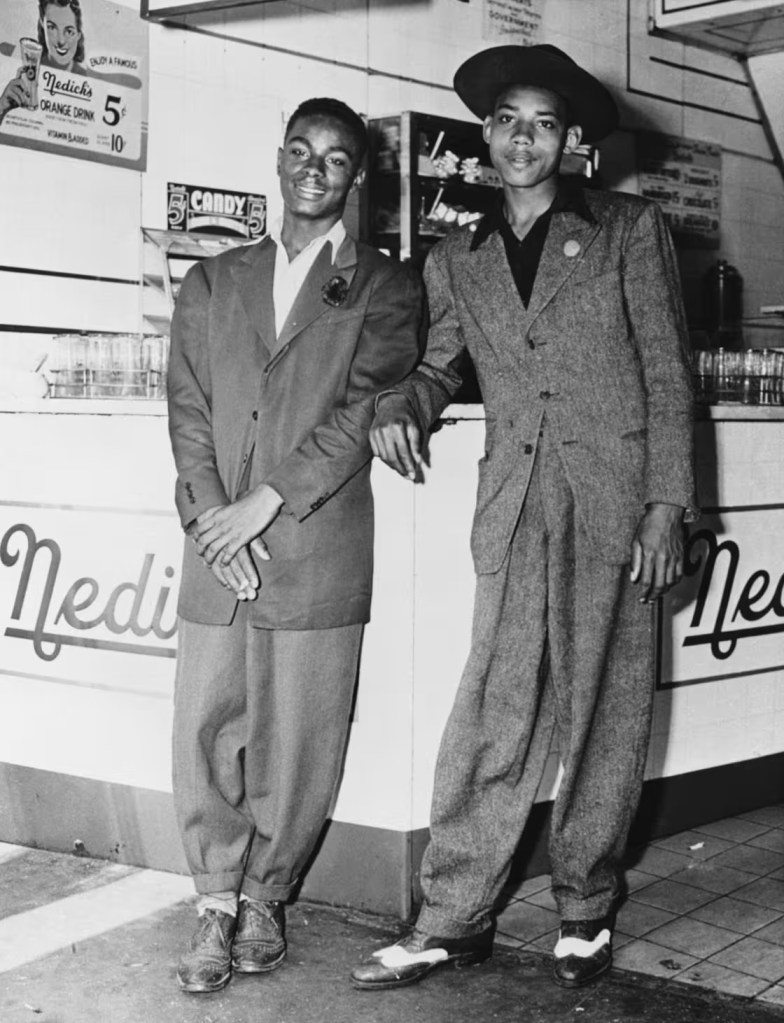

En la Gala del Met dedicada al Dandy Negro que acaba de tener lugar hace horas en el Metropolitan Museum de New York, todo es figura sin agenciamiento. Lo que antes fue contra-discurso —como la elegancia radical de los sapeurs en el Congo, o el cool insurgente del Harlem Renaissance— hoy se adapta a la lógica de una industria del lujo en alarmante decadencia por la guerra de tarifas lanzada por Trump. En el régimen visual que impone Anna Wintour desde su trono blanco, el cuerpo negro puede ocupar el centro… siempre que esté editado, domesticado, excepcional. Ni masivo, ni criminalizado, ni en fuga.

En el régimen visual que impone Anna Wintour desde su trono blanco, el cuerpo negro puede ocupar el centro… siempre que esté editado, domesticado.

Tweet

No se trata solo de cómo el dandismo se estetiza, sino de qué cuerpos negros son aceptados como imagen de moda y cuáles permanecen invisibles, encarcelados, excluidos. El Met no es inclusivo: es curatorialmente segregativo. Y eso se evidencia no solo en la pasarela, sino en los gestos de backstage.

No se trata solo de cómo el dandismo se estetiza, sino de qué cuerpos negros son aceptados como imagen de moda y cuáles permanecen invisibles, encarcelados, excluidos.

Tweet

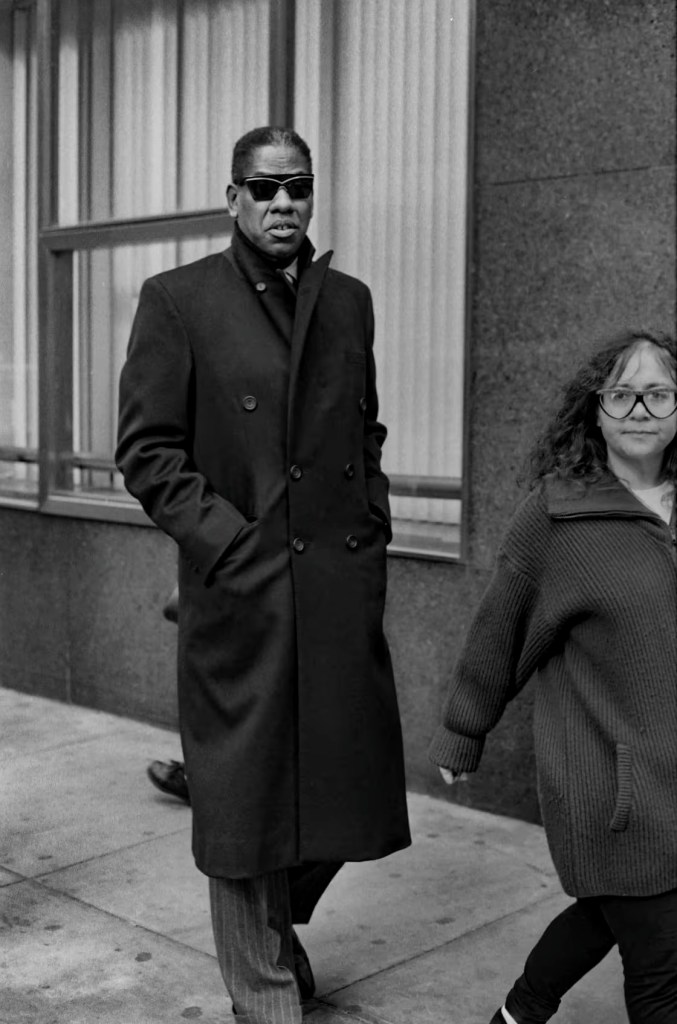

El despido humillante de André Leon Talley —asesor negro histórico de Wintour, figura clave de la sofisticación editorial— no fue una anécdota, sino una afirmación de jerarquía racial. A la gala pueden entrar los cuerpos negros bellos y dóciles, pero no los cuerpos negros que piensan, organizan o interpelan al poder blanco.

El despido humillante de André Leon Talley —asesor negro histórico de Wintour, figura clave de la sofisticación editorial— no fue una anécdota, sino una afirmación de jerarquía racial

Tweet

Sí, es cierto: Wintour se opone a Trump, pero lo hace desde una blancura ilustrada que nunca arriesga su lugar. Su antagonismo es estético, no estructural. Y en ese sentido, el Black dandy del Met se vuelve también rehén: símbolo de inclusión para un sistema que aún llena sus cárceles con hombres negros pobres. El crimen es racializado, pero la elegancia también. Y lo que no entra en el moodboard de la gala, sigue siendo objeto de castigo.

Wintour se opone a Trump, pero lo hace desde una blancura ilustrada que nunca arriesga su lugar. Su antagonismo es estético, no estructural.

Tweet

Como recuerda Angela Davis, no se puede hablar de libertad negra sin confrontar el sistema penal como máquina de continuidad del racismo. Ruth Wilson Gilmore, por su parte, lo dice con claridad brutal: “la carcelación masiva no es un fracaso del sistema, es la manera en que el sistema funciona”. Mientras un puñado de cuerpos negros son elevados a la categoría de íconos en la pasarela de Wintour, millones de otros son marcados por la sospecha, el castigo y la invisibilidad. La gala no corrige esa estructura: la estetiza. Y al hacerlo, convierte al Black dandy —figura histórica de astucia política y desplazamiento semiótico— en testimonio silencioso de una victoria blanca sobre lo negro. No una victoria violenta, sino sofisticada, editorializada, curada: una victoria que se llama moda.

La gala no corrige esa estructura: la estetiza. Y al hacerlo, convierte al Black dandy —figura histórica de astucia política y desplazamiento semiótico— en testimonio silencioso de una victoria blanca sobre lo negro

Tweet

Sabotaje del archivo: No se trata de verse bien, sino de no dejarse mirar del todo.

Frente a la estetización curada de lo negro en espacios como la Met Gala —donde la inclusión es posible solo si se editorializa el cuerpo, se decora la diferencia y se silencia el conflicto—, algunos artistas y diseñadores negros han desarrollado lenguajes que rehúyen la captura y devuelven al estilo su filo político. No se trata solo de vestirse, sino de cargar la ropa de memoria, de ira, de duelo, de historia no digerida.

El trabajo de diseñadores como Telfar Clemens, por ejemplo, subvierte la lógica aspiracional del lujo: no hay exclusividad, no hay lista de espera, no hay jerarquía. Sus bolsos no gender, no gatekeeping desmantelan el fetiche racializado del objeto inaccesible. El archivo vivo de Kehinde Wiley —con sus retratos barrocos de cuerpos negros queerizados en poses aristocráticas— pone en escena no una integración, sino una inversión violenta del canon. Más cerca del sabotaje que de la celebración, sus pinturas incomodan porque devuelven a los cuerpos negros el poder de mirar.

Lo mismo ocurre con las performances de Jacolby Satterwhite o las esculturas funerarias de Simone Leigh: no piden entrar al museo, lo infectan. Producen un tipo de belleza que no puede ser digerida por el régimen blanco de la moda porque está cargada de duelo, de cosmología ancestral, de códigos que no se traducen.

El dandismo negro, en este registro, no es ya un gesto de adaptación al lujo blanco, sino una forma de archivo insurgente: una forma de vestirse de historia, de aparecer en exceso, de ser too much para el ojo blanco. De resistir, incluso, al deseo de ser deseado por el centro.

Sabotaje desde adentro: cuando el cuerpo negro no se deja curar

Aunque la Met Gala 2025 fue, en líneas generales, una ceremonia de contención racial cuidadosamente estilizada, hubo excepciones incómodas. No por provocativas en un sentido literal, sino porque interrumpieron la gramática editorial del evento. Uno de esos gestos fue el de Jordan Roth, quien apareció con una estructura escultórica firmada por Simone Leigh, un manto funerario que evocaba tanto la arquitectura ritual yoruba como los caparazones protectores de esclavas fugitivas. Sin cuerpo expuesto, sin silueta celebratoria, la pieza recordaba más a un altar que a un vestido. En lugar de integrarse, sobrecargaba el sentido, devolviendo a la moda su carga de duelo y de archivo racial.

Aunque la Met Gala 2025 fue, en líneas generales, una ceremonia de contención racial hubo excepciones que interrumpieron la gramática editorial del evento.

Tweet

Otro momento significativo fue la aparición de Kelela, envuelta en un diseño de Telfar Clemens reinterpretado como un collage de prendas fragmentadas: jeans deshilachados, camisetas con manchas de tierra y bolsos de supermercado bordados con nombres de mujeres negras asesinadas por la policía. No había lujo aquí, sino duelo, rutina, memoria. El gesto no era editorializable: era una escena de sobrevida.

Incluso A$AP Rocky, a menudo cómodo en el circuito de moda blanca, optó esta vez por un traje sin forma hecha de retazos de uniformes penitenciarios y denim intervenido con frases tomadas de discursos de Angela Davis y Mumia Abu-Jamal. En lugar de brillar, su look parecía pedir silencio. No se trataba de estilizar el sufrimiento, sino de inscribirlo como materia ineludible en un espacio que suele invisibilizarlo bajo lentejuelas.

A$AP Rocky, a menudo cómodo en el circuito de moda blanca, optó esta vez por un traje sin forma hecha de retazos de uniformes penitenciarios

Tweet

Estos gestos no interrumpieron el evento —sería ingenuo pensarlo—, pero sí introdujeron una grieta: la grieta entre el cuerpo que desfila y el cuerpo que denuncia, entre la belleza capturable y la historia que no se deja vestir. Lo que hicieron no fue ser inclusivos, sino sabotear desde adentro. Llevar el duelo a la gala. Llevar el archivo a la pasarela. Hacer que el ojo blanco tropiece en su propio algoritmo.

La mirada blanca, siempre la mirada blanca

Para comprender lo que está en juego en estos gestos de sabotaje simbólico dentro de la Met Gala, es necesario examinar el dispositivo más profundo que regula lo visible: la mirada blanca. En Black Looks: Race and Representation, bell hooks denuncia cómo la blancura no es solo un color o una identidad, sino una posición de control visual. La mirada blanca —dice— no solo mira: posee. Se apropia, exotiza, simplifica. Reduce al cuerpo negro a objeto de deseo o temor, pero nunca lo reconoce como sujeto soberano. Incluso cuando parece celebrar la diferencia, lo hace desde un régimen de dominación estética que decide qué formas de negritud son aceptables y cuáles no.

La mirada blanca no solo mira: posee. Se apropia, exotiza, simplifica. Reduce al cuerpo negro a objeto de deseo o temor, pero nunca lo reconoce como sujeto.

Tweet

En el contexto de la moda, esa mirada blanca se vuelve algoritmo. No solo ve: curatorializa. Estiliza el cuerpo negro para que sea vendible, admirable, compartible. Pero como advirtió Édouard Glissant, la opacidad es también un derecho. En su Poética de la Relación, Glissant reclama el poder de no explicarse ante el blanco, de no ser transparente, de no traducirse. Y ahí es donde algunos gestos en la Met 2025 se vuelven radicales: no porque sean escandalosos, sino porque resisten la traducción. No están hechos para la comprensión blanca, sino para sostener un enigma, un duelo, una memoria que no se deja curar.

Cuando Kelela aparece vestida con restos, cuando el cuerpo de A$AP Rocky se vuelve ilegible, cuando Colman convierte un vestido en altar, lo que se pone en escena es precisamente eso: un exceso que no se deja mirar del todo. Una afirmación estética que no busca ser deseada, sino preservada. No como reliquia, sino como archivo vivo que desborda al ojo blanco que quiere editorializarlo todo.

Tirar ácido al ojo blanco?

La Met Gala, es una tecnología cultural del poder blanco: selecciona, estiliza e incluye lo negro en tanto figura editorializable. El Black dandy, antes operador de subversión simbólica, hoy aparece como ícono perfectamente integrado. Frente al ojo que todo lo cura, todo lo traduce, todo lo convierte en estética —ese ojo blanco disfrazado de algoritmo editorial—, estas presencias negras afirman otra cosa: el derecho a no explicarse. El derecho a vestirse de historia, de rabia, de irreductible belleza. El derecho, incluso, a no ser vistos. Porque a veces, en el mundo de la moda, lo verdaderamente radical no es aparecer: es resistirse a ser capturado.

El Black dandy, antes operador de subversión simbólica, hoy aparece como ícono perfectamente integrado.

Tweet

A$AP Rocky and colman domingo Shatter the Unbearably Liberal Mirror of the Met Gala

At the Met Gala just held hours ago at the Metropolitan Museum in New York, dedicated to the Black Dandy, everything is figure without agency. What was once counter-discourse —like the radical elegance of the sapeurs in Congo or the insurgent cool of the Harlem Renaissance— now adapts to the logic of a luxury industry in alarming decline amid Trump’s tariff wars. In the visual regime imposed by Anna Wintour from her white throne, the Black body can occupy center stage… so long as it is edited, domesticated, exceptional. Neither mass, nor criminalized, nor fugitive.

In the visual regime imposed by Anna Wintour from her white throne, the Black body can occupy center stage… so long as it is edited, domesticated, exceptional.

Tweet

This is not just about how dandyism is aestheticized, but about which Black bodies are accepted as fashion images and which remain invisible, incarcerated, or excluded. The Met is not inclusive: it is curatorial in its segregation. And that is evident not just on the runway, but behind the scenes. The humiliating dismissal of André Leon Talley —Wintour’s longtime Black advisor and a key figure of editorial sophistication— was no anecdote; it was an assertion of racial hierarchy. Beautiful, docile Black bodies may enter the gala, but not those that think, organize, or confront white power.

The humiliating dismissal of André Leon Talley —Wintour’s longtime Black advisor and a key figure of editorial sophistication— was no anecdote; it was an assertion of racial hierarchy.

Tweet

Yes, Wintour opposes Trump, but she does so from an enlightened whiteness that never risks its place. Her antagonism is aesthetic, not structural. And in that sense, the Black dandy of the Met becomes a hostage too: a symbol of inclusion for a system that still fills its prisons with poor Black men. Crime is racialized, but so is elegance. What doesn’t make it onto the gala’s moodboard remains subject to punishment.

Crime is racialized, but so is elegance. What doesn’t make it onto the gala’s moodboard remains subject to punishment.

Tweet

As Angela Davis reminds us, we cannot speak of Black freedom without confronting the penal system as a continuity machine of racism. Ruth Wilson Gilmore puts it bluntly: “mass incarceration is not a failure of the system; it is how the system works.” While a handful of Black bodies are elevated to the status of icons on Wintour’s runway, millions more are marked by suspicion, punishment, and invisibility. The gala doesn’t correct that structure: it aestheticizes it. And in doing so, it turns the Black dandy —a historical figure of political cunning and symbolic displacement— into a silent witness to a white victory over Blackness. Not a violent victory, but a sophisticated, editorialized, curated one: a victory called fashion.

Archival sabotage: It’s not about looking good, but refusing to be seen

Faced with the curated aestheticization of Blackness in spaces like the Met Gala —where inclusion is only possible if the body is editorialized, difference is decorated, and conflict is silenced— some Black artists and designers have developed languages that evade capture and return style to its political edge. It’s not just about dressing, but about clothing oneself in memory, in rage, in mourning, in undigested history.

It’s not just about dressing, but about clothing oneself in memory, in rage, in mourning, in undigested history. The Met erases that.

Tweet

Designers like Telfar Clemens, for example, subvert the aspirational logic of luxury: there’s no exclusivity, no waitlist, no hierarchy. His no-gender, no-gatekeeping bags dismantle the racialized fetish of the inaccessible object. The living archive of Kehinde Wiley —with his baroque portraits of queer Black bodies in aristocratic poses— stages not integration but a violent inversion of the canon. Closer to sabotage than celebration, his paintings unsettle because they return the gaze to the Black body.

The same applies to the performances of Jacolby Satterwhite or the funerary sculptures of Simone Leigh: they do not ask to enter the museum, they infect it. They produce a kind of beauty that cannot be digested by the white regime of fashion, because it is saturated with mourning, ancestral cosmology, and untranslated codes.

In this register, Black dandyism is no longer a gesture of adaptation to white luxury, but a form of insurgent archiving: a way of dressing in history, appearing in excess, being too much for the white gaze. Of resisting, even, the desire to be desired by the center.

Sabotage from within: when the Black body refuses to be cured

Though the Met Gala 2025 was, overall, a carefully stylized ceremony of racial containment, there were uncomfortable exceptions. Not provocative in a literal sense, but disruptive to the event’s editorial grammar. One such gesture came from Jordan Roth, who arrived cloaked in a sculptural piece by Simone Leigh—a funerary shroud evoking both Yoruba ritual architecture and the protective shells of fugitive slave women. With no exposed body, no celebratory silhouette, the piece resembled an altar more than a dress. Rather than integrate, it overloaded the space with meaning, returning mourning and racial archive to fashion.

Another striking moment came from Kelela, wrapped in a Telfar Clemens design reimagined as a fragmented collage: frayed jeans, dirt-stained t-shirts, and supermarket bags embroidered with the names of Black women killed by police. There was no luxury here—only mourning, routine, memory. The gesture was not editorializable: it was a scene of survival.

Even A$AP Rocky, often at ease in white fashion circuits, opted this time for a shapeless outfit crafted from prison uniforms and denim stitched with quotes from Angela Davis and Mumia Abu-Jamal. Rather than shine, his look seemed to demand silence. It wasn’t about styling suffering, but inscribing it as an inescapable presence in a space that usually buries it beneath sequins.

Even A$AP Rocky, often at ease in white fashion circuits, opted this time for a shapeless outfit crafted from prison uniforms and denim stitched with quotes from Angela Davis and Mumia Abu-Jamal.

Tweet

These gestures didn’t interrupt the event —that would be naive to assume— but they did introduce a fissure: the crack between the body that struts and the body that denounces, between capturable beauty and history that refuses to be dressed. What they did was not inclusion, but sabotage from within. Bringing mourning to the gala. Bringing the archive to the runway. Making the white gaze stumble over its own algorithm.

The white gaze, always the white gaze

To understand what is at stake in these acts of symbolic sabotage within the Met Gala, we must examine the deeper mechanism that governs the visible: the white gaze. In Black Looks: Race and Representation, bell hooks shows how whiteness is not just a color or identity, but a position of visual control. The white gaze, she writes, does not merely look: it possesses. It appropriates, exoticizes, simplifies. It reduces the Black body to an object of desire or fear, but never recognizes it as a sovereign subject. Even when it seems to celebrate difference, it does so through a regime of aesthetic domination that decides which forms of Blackness are acceptable and which are not.

In fashion, the white gaze becomes algorithm. It doesn’t just see: it curates. It stylizes the Black body to make it sellable, admirable, shareable. But as Édouard Glissant insisted, opacity is a right. In his Poetics of Relation, Glissant calls for the power not to explain oneself to whiteness, not to be transparent, not to be translated. And this is where certain gestures at the 2025 Met Gala become radical—not because they’re scandalous, but because they resist translation. They are not made for white understanding, but to sustain an enigma, a grief, a memory that refuses to be cured.

When Kelela appears clothed in remnants, when A$AP Rocky’s body becomes unreadable, when Colman turns a dress into an altar, what is staged is precisely that: an excess that refuses full visibility. An aesthetic affirmation that does not seek to be desired, but to be preserved. Not as relic, but as living archive that overflows the white eye that wants to editorialize everything.

When Kelela appears clothed in remnants, when A$AP Rocky’s body becomes unreadable, when Colman turns a dress into an altar, what is staged is precisely that: an excess that refuses full visibility.

Tweet

Throw acid at the white gaze?

The Met Gala is a cultural technology of white power: it selects, stylizes, and includes Blackness insofar as it is editorializable. The Black dandy, once a figure of symbolic subversion, now appears as a perfectly integrated icon. Confronted with the eye that heals everything, translates everything, turns everything into aesthetics—that white eye disguised as editorial algorithm—these Black presences assert something else: the right not to explain. The right to dress in history, in rage, in irreducible beauty. The right, even, not to be seen. Because sometimes, in the world of fashion, the truly radical act is not to appear—but to refuse capture.

Deja una respuesta