Scroll Down the Post for the English Version

Nerón

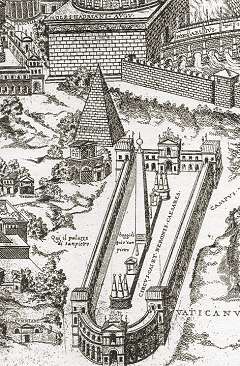

En el balcón central de la Basílica de San Pedro, bajo el sol cálido de mayo, León XIV apareció para pronunciar las primeras palabras de su pontificado. La fórmula ritual del Habemus Papam ya había resonado desde lo alto de las logias vaticanas, pero lo que siguió fue algo inesperado. Frente a él, una multitud vibrante y predominantemente joven, con banderas de Perú, México, Argentina y Estados Unidos, llenaba la plaza en una coreografía de fe que parecía desafiar las convenciones de una Europa envejecida y desencantada. Pero más allá de las cabezas descubiertas y los brazos en alto, el Papa enfrentaba también el antiguo obelisco egipcio que domina el centro de la plaza, un monolito traído desde Heliópolis y erigido en el Circo de Nerón, donde los primeros cristianos fueron martirizados. Ese mismo Nerón, símbolo de la decadencia imperial y la persecución injusta, parece reencarnado hoy en figuras como Donald Trump, a quien León XIV aborrece. La historia, como la piedra del obelisco, sigue en pie, pero las fuerzas que ahora se congregan en su sombra parecen decididas a resistir.

Leon XIV enfrentó el antiguo obelisco del Circo de Nerón, donde los primeros cristianos fueron martirizados. Ese mismo Nerón, reencarnado en Donald Trump, a quien aborrece.

Tweet

Perugino

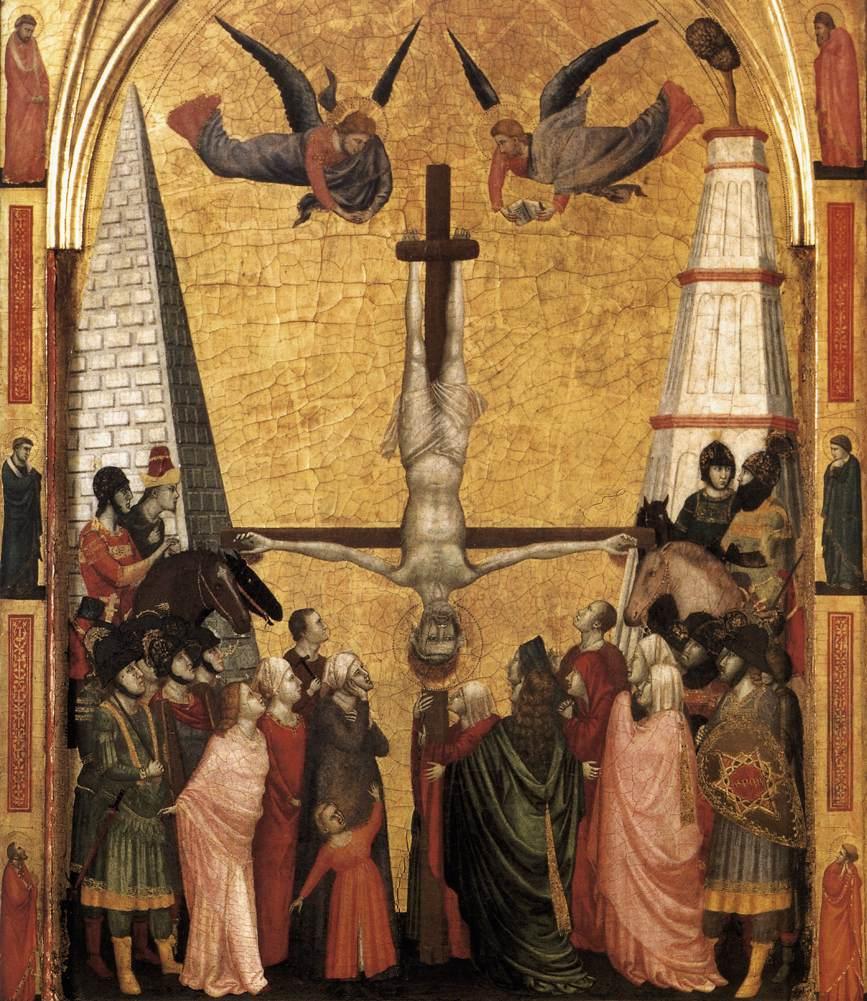

Leon XIV, el nuevo Papa, venia directo del Cónclave que lo eligió: en el corazón de la Capilla Sixtina, entre los frescos que narran la historia de la salvación, se encuentra una obra que cristaliza el fundamento mismo del poder papal: El Cristo entregando las llaves a San Pedro (1481-1482) de Pietro Perugino. Esta pintura, encargada para celebrar la autoridad divina conferida al primer pontífice, representa el momento fundacional en que Cristo, de pie en el centro de una plaza abierta, extiende las llaves del Reino de los Cielos a Pedro, símbolo de la autoridad para atar y desatar, para abrir y cerrar las puertas del perdón y la condena. Las dos llaves –una de oro y otra de plata– simbolizan el poder espiritual y temporal que, desde ese momento, queda en manos del sucesor de Pedro.

Marte

En el fondo de esta escena se alza un templo circular, una estructura idealizada que evoca tanto la perfección de la ciudad celestial como la autoridad eterna de Roma. Esta forma arquitectónica remite al Baptisterio de San Giovanni en Florencia, uno de los edificios más antiguos y simbólicos del cristianismo occidental, donde generaciones de florentinos –incluidos miembros de la familia Medici– fueron bautizados. El octógono del baptisterio, con sus relieves en bronce que representan escenas bíblicas, es un precursor de las ambiciones monumentales del Renacimiento, cuando las familias poderosas como los Medici utilizaban el arte no solo como manifestación religiosa, sino como un instrumento de diplomacia y poder.

Lorenzo, Il Magnifico marca con el fresco y Perugino en la Capilla Sixtina y continúa con los Papas Medici llamados León

Tweet

En la línea de los Leones Medici

Lorenzo de Medici, conocido como Il Magnifico, fue maestro en esta forma de diplomacia cultural. Sus comisiones a artistas como Botticelli, Ghirlandaio y el propio Perugino no solo embellecen Florencia, sino que proyectaban su influencia más allá de Toscana, consolidando alianzas y reafirmando su control sobre el destino espiritual y político de Italia. Esta visión culminó en los papados de dos de sus descendientes directos que adoptaron el nombre León:

León X (Giovanni di Lorenzo de’ Medici) – Elegido papa en 1513, fue hijo de Lorenzo el Magnífico. León X es recordado como el gran mecenas del Alto Renacimiento, responsable de financiar a artistas como Rafael, Miguel Ángel y Bramante.

Tweet

León X (Giovanni di Lorenzo de’ Medici) – Elegido papa en 1513, fue hijo de Lorenzo el Magnífico. León X es recordado como el gran mecenas del Alto Renacimiento, responsable de financiar a artistas como Rafael, Miguel Ángel y Bramante. Sin embargo, su esplendor cultural se vio opacado por su fracaso en comprender la magnitud de la Reforma Protestante que se gestaba en el norte de Europa. Fue bajo su pontificado que Martín Lutero clavó sus 95 tesis en la puerta de la iglesia de Wittenberg, marcando el inicio de la fragmentación del cristianismo occidental. Para muchos, León X encarna tanto el apogeo artístico como la decadencia moral de la Iglesia renacentista pero, en realidad, esto es porque fue un Papa que quiso dar mas lugar a las mujeres en la Iglesia.

León XI (Alessandro Ottaviano de’ Medici) – Aunque su pontificado fue breve –solo 27 días en 1605–, su elección como papa fue vista como una continuación del poder Medici en el Vaticano. Aunque menos conocido, su fugaz papado es simbólico del poder efímero y las intrigas políticas que caracterizaron a los Medici en su fase final.

El dilema capitalista

Sin embargo, es importante no confundir esta tradición con la figura de León XIII, quien gobernó la Iglesia entre 1878 y 1903. Nacido como Vincenzo Gioacchino Pecci, no era un Medici, sino un intelectual profundamente preocupado por las transformaciones de la modernidad, conocido por su encíclica Rerum Novarum (1891), que intentó reconciliar la doctrina católica con las nuevas demandas sociales y políticas de la era industrial. Su problema era el capitalismo.

León XIII firmó la encíclica Rerum Novarum (1891), que intentó reconciliar la doctrina católica con las nuevas demandas sociales y políticas de la era industrial. Su problema era el capitalismo y su preocupación la justicia social.

Tweet

El Cyber-Papa Post-Capitalista

El 8 de mayo de 2025, esas llaves simbólicas pasaron a manos de León XIV, nacido como Robert Francis Prevost, el primer Papa estadounidense, con profundas raíces misioneras en Perú, donde sirvió como obispo de Chiclayo antes de ser llamado a Roma como prefecto del Dicasterio para los Obispos. Su elección, en un cónclave sorprendentemente breve, es un puente entre Norteamérica y Sudamérica, uniendo dos continentes que han sido históricamente marginados dentro de la estructura de poder eclesiástica. Es como si el cónclave hubiera dicho: “La próxima fase es post-neoliberal, es alegre, es bella y esa belleza es lo humano”. Este es el Cyber-Papa que reflexionará sobre la Inteligencia Artificial y la manipulación genética. Tiene que ser un Papa pensador.

Leon XIV es el Cyber-Papa que reflexionará sobre la Inteligencia Artificial y la manipulación genética. Tiene que ser un Papa pensador.

Tweet

En la Plaza de San Pedro, bajo el cielo luminoso de primavera, la multitud celebró con gritos de júbilo el anuncio de León XIV. Había en el aire una juventud y belleza que, con el encuadre de las colosales columnas de Bernini y la fuerza escultural de la fachada Stefano Maderno, devolvía esperanza a un mundo que parece haberse olvidado de lo humano. No porque haya que ser lindo para tener fe, sino porque la esperanza es, en sí misma, una forma de belleza. Frente a los rostros marchitos y las voces desgastadas de líderes decadentes como Trump y Milei, que parecen pasados de todo y atrapados en sus propias fantasías de poder, la plaza de San Pedro mostró otra forma de ser humano. La cruz papal fue llevada por un negro y fue un africano el que abrió el camino para el Papa Americano que hablo en italiano, en español y en latín.

Un misionero introspectivo pero combativo

Pero, ¿quién es realmente León XIV? Para entender su enfoque como Papa, es esencial recordar que es miembro de la Orden de San Agustín (OSA). Ser agustino implica más que una simple afiliación religiosa; es una forma de vida que combina la contemplación interior con la acción pastoral. Los agustinos siguen las enseñanzas de San Agustín de Hipona, el gran teólogo del siglo IV cuyo lema, “In interiore homine habitat veritas” (“En el interior del hombre habita la verdad”), resume su profunda búsqueda de Dios a través de la introspección. Para los agustinos, la vida en comunidad es una expresión tangible del amor de Dios, un reflejo de la Trinidad, y un compromiso con la conversión continua del corazón. Es una orden que reflexiona sobre ‘lo humano’.

No es casualidad, entonces, que León XIV haya criticado públicamente a líderes como Donald Trump y sus aliados ultraconservadores en Estados Unidos. En redes sociales, rechazó las interpretaciones excluyentes del cristianismo que justifican políticas antiinmigrantes, como las del vicepresidente J.D. Vance, afirmando que “Jesús no nos pide que clasifiquemos nuestro amor por los demás”. Esta postura sugiere que el nuevo Papa podría desafiar las narrativas neoliberales que han dominado gran parte del discurso político y económico global en las últimas décadas, muchas veces promovidas por instituciones como el Council of the Americas. Este Papa no es un pastor como Francisco y no predica con el ejemplo sino que tiene una misión y es un Papa listo para la batalla. Si había algo que Francisco carecía por sus propias posiciones era de iniciativa. El podia dar el ejemplo pero no podia accionar demasiado. Este va a ser un Papa de acción.

León XIV es abiertamente crítico de Donald Trump y sus aliados ultraconservadores en Estados Unidos. En redes sociales, rechazó a J.D. Vance, afirmando que “Jesús no nos pide que clasifiquemos nuestro amor por los demás”.

Tweet

Así como el baptisterio de Florencia marcaba el inicio de la vida cristiana para los Medici, el templo circular de Perugino simboliza un poder que trasciende los siglos y que, interesantemente, esta construido sobre un viejo templo a Marte, el dios pagano de la guerra. Ahora, el papa norteamericano que habló primero en castellano que en inglés, apela a ejercer una autoridad que puede cambiar el Imperio Norteamericano desde adentro porque, sospecho, entiende que es un país quebrado moralmente. Latinoamérica es diferente. Tiene todo el potencial.

En el eco de los vítores de San Pedro, resuena la esperanza de un nuevo capítulo para la Iglesia, una oportunidad para crear puentes en un mundo dividido. Si el ser demasiado humano de Francisco lo hacía casi un superhombre, este es un papa humano que viene de una orden que sabe lo que significa ser humano y sabe de su poder y tengo la sospecha que lo va a usar.

The Keys of the Kingdom: Leo XIV, the Medici Legacy, and the Rejection of Empire

From the central balcony of St. Peter’s Basilica, under the warm May sun, Leo XIV stepped forward to deliver the first words of his pontificate. The ritual formula of Habemus Papam had already echoed from the heights of the Vatican loggias, but what followed was something unexpected. Before him, a vibrant and predominantly young crowd, waving flags from Peru, Mexico, Argentina, and the United States, filled the square in a choreography of faith that seemed to defy the conventions of an aging and disenchanted Europe. But beyond the bare heads and raised arms, the Pope also faced the ancient Egyptian obelisk that dominates the center of the square—a monolith brought from Heliopolis and erected in Nero’s Circus, where the first Christians were martyred. That same Nero, a symbol of imperial decadence and unjust persecution, seems reincarnated today in figures like Donald Trump, whom Leo XIV abhors. History, like the stone of the obelisk, still stands, but the forces now gathering in its shadow seem determined to resist.

The new Pope faced the ancient Egyptian obelisk from Nero’s Circus, where the first Christians were martyred. Nero is today a symbol of Donald Trump, whom Leo XIV abhors.

Tweet

Leo XIV, the new Pope, had just emerged from the conclave that elected him: in the heart of the Sistine Chapel, surrounded by frescoes that narrate the history of salvation, stands a work that crystallizes the very foundation of papal power: Christ Giving the Keys to Saint Peter (1481-1482) by Pietro Perugino. This painting, commissioned to celebrate the divine authority conferred on the first pontiff, depicts the foundational moment when Christ, standing in the center of an open plaza, extends the keys of the Kingdom of Heaven to Peter—a symbol of the authority to bind and loose, to open and close the gates of forgiveness and condemnation. The two keys—one gold, one silver—symbolize the spiritual and temporal power that, from that moment, would rest in the hands of Peter’s successors.

In the background of this scene stands a circular temple, an idealized structure that evokes both the perfection of the heavenly city and the eternal authority of Rome. This architectural form recalls the Baptistery of San Giovanni in Florence, one of the oldest and most symbolic buildings in Western Christianity, where generations of Florentines—including members of the Medici family—were baptized. The octagon of the baptistery, with its bronze reliefs depicting biblical scenes, is a precursor to the monumental ambitions of the Renaissance, when powerful families like the Medici used art not only as a religious manifestation but as an instrument of diplomacy and power.

Lorenzo de’ Medici, known as Il Magnifico, was a master of this form of cultural diplomacy. His commissions to artists like Botticelli, Ghirlandaio, and Perugino not only beautified Florence but projected his influence beyond Tuscany, consolidating alliances and reaffirming his control over the spiritual and political destiny of Italy. This vision culminated in the papacies of two of his direct descendants:

Lorenzo de’ Medici, known as Il Magnifico, was a master of artistic and cultural diplomacy. His commissions to artists like Botticelli, Ghirlandaio, and Perugino not only beautified Florence but projected his influence in the Papacy with two Medici Popes named Leo.

Tweet

Leo X (Giovanni di Lorenzo de’ Medici) – Elected pope in 1513, he was the son of Lorenzo the Magnificent. Leo X is remembered as the great patron of the High Renaissance, responsible for funding artists like Raphael, Michelangelo, and Bramante. However, his cultural splendor was overshadowed by his failure to grasp the magnitude of the Protestant Reformation that was brewing in northern Europe. It was under his pontificate that Martin Luther nailed his 95 Theses to the door of the church in Wittenberg, marking the beginning of the fragmentation of Western Christianity. For many, Leo X embodies both the artistic peak and the moral decadence of the Renaissance Church, although in reality, this was partly because he sought to give women a greater role in the Church, a move that provoked fierce resistance.

Leo X embodies both the artistic peak and the moral decadence of the Renaissance Church, although in reality, this was partly because he sought to give women a greater role in the Church, a move that provoked fierce resistance.

Tweet

Leo XI (Alessandro Ottaviano de’ Medici) – Although his pontificate was brief—only 27 days in 1605—his election as pope was seen as a continuation of Medici power in the Vatican. Though less well-known, his fleeting papacy is symbolic of the ephemeral power and political intrigues that characterized the Medici in their final phase.

However, it is important not to confuse this tradition with the figure of Leo XIII, who governed the Church from 1878 to 1903. Born as Vincenzo Gioacchino Pecci, he was not a Medici but an intellectual deeply concerned with the transformations of modernity. He is known for his encyclical Rerum Novarum (1891), which sought to reconcile Catholic doctrine with the new social and political demands of the industrial age. His struggle was not with the Reformation but with the unchecked forces of capitalism.

On May 8, 2025, these symbolic keys passed into the hands of Leo XIV, born as Robert Francis Prevost, the first American pope, with deep missionary roots in Peru, where he served as bishop of Chiclayo before being called to Rome as prefect of the Dicastery for Bishops. His election, in a surprisingly brief conclave, forms a bridge between North and South America, uniting two continents that have been historically marginalized within the power structures of the Church. It is as if the conclave had declared: “The next phase is post-neoliberal, it is joyful, it is beautiful, and that beauty is human.”

The Conclave had declared: “The next phase is post-neoliberal, it is joyful, it is beautiful, and that beauty is human. It is also the one that deals with genetic manipulation and AI.

Tweet

In St. Peter’s Square, under the bright spring sky, the crowd erupted in jubilant cheers at the announcement of Leo XIV. There was a sense of youth and beauty in the air that, framed by the colossal columns of Bernini and the sculptural power of the facade by Stefano Maderno, restored hope to a world that seems to have forgotten what it means to be human. Not because one must be beautiful to have faith, but because hope itself is a form of beauty. In contrast to the withered faces and exhausted voices of decadent leaders like Trump and Milei, who seem past their prime and trapped in their own fantasies of power, St. Peter’s Square offered another vision of what it means to be human. The papal cross was carried by a Black man, and it was an African who opened the way for the American pope who spoke in Italian, Spanish, and Latin.

But who is Leo XIV, really? To understand his approach as pope, it is essential to remember that he is a member of the Order of St. Augustine (OSA). Being an Augustinian means more than a simple religious affiliation; it is a way of life that combines deep interior contemplation with active pastoral work. Augustinians follow the teachings of St. Augustine of Hippo, the great fourth-century theologian whose motto, “In interiore homine habitat veritas” (“The truth dwells in the inner man”), captures his profound search for God through introspection. For Augustinians, community life is a tangible expression of God’s love, a reflection of the Trinity, and a commitment to the continuous conversion of the heart.

Augustinians follow the teachings of St. Augustine of Hippo, the great fourth-century theologian whose motto, “In interiore homine habitat veritas” (“The truth dwells in the inner man”), captures his profound search for God through introspection

Tweet

It is no coincidence, then, that Leo XIV has publicly criticized leaders like Donald Trump and his ultraconservative allies in the United States. On social media, he has rejected the exclusionary interpretations of Christianity that justify anti-immigrant policies, like those of Vice President J.D. Vance, asserting that “Jesus does not ask us to rank our love for others.” This stance suggests that the new Pope may challenge the neoliberal narratives that have dominated much of the global political and economic discourse in recent decades.

Deja una respuesta