Scroll Down for the English Version

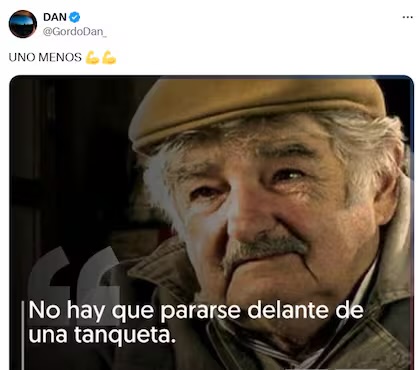

El 14 de mayo, apenas confirmada la muerte de “Pepe” Mujica, el Gordo Dan —médico de formación y figura hegemónica del ciberespacio libertario— publicó en X lo siguiente: “Uno menos.”

Tweet

El 14 de mayo, apenas confirmada la muerte de José “Pepe” Mujica, el Gordo Dan —médico de formación y figura hegemónica del ciberespacio libertario— publicó en X lo siguiente: “Uno menos.” El post, celebrado con miles de likes, no se limitó a expresar un desacuerdo político, ni siquiera un desprecio ideológico: fue una celebración de una muerte. ¿Qué implica que un médico, alguien entrenado para preservar la vida, celebre públicamente la muerte de un expresidente cuya trayectoria estuvo marcada por la sobriedad, la resistencia y una ética republicana ajena al cinismo? La pregunta no es moral, sino de sentido común: ¿qué tipo de subjetividad política se construye cuando la muerte del otro —no su derrota, no su error, sino su desaparición— se vuelve motivo de goce compartido?

La pregunta no es moral, sino de sentido común: ¿qué tipo de subjetividad política se construye cuando la muerte del otro —no su derrota, no su error, sino su desaparición— se vuelve motivo de goce compartido?

Tweet

Lo que celebraron en misa de necromancia con la muerte de Mujica, el Gordon Dan y su séquito de cadetes de obediencia debida, no fue sólo un cadaver, sino el desmonte de una figura que, aun desde su marginalidad institucional, representaba una amenaza para la estabilidad emocional que el nuevo orden afectivo del post-neoliberalismo tardío aporta a este medico. Ese orden post-económico no requiere adhesiones sino rechazos; no construye futuro, sino que se alimenta de la destrucción… del pasado. El festejo del Gordo Dan no es un gesto marginal, sino un síntoma de una forma de gobierno en la que la soberanía se ejerce no garantizando vida, sino decidiendo quién merece morir, ser olvidado o degradado.

Su necromancia no parte de un cadaver, sino del desmonte de una figura que, aun desde su marginalidad institucional, representó una amenaza para su precaria estabilidad emocional.

Tweet

En este marco, la figura de Mujica resulta intolerable no por su poder, sino por su residuo ético. Su austeridad no es eficaz, pero es ejemplar. Su biografía no es heroica, pero es resistente. En un sistema que ha vaciado toda sustancia simbólica en nombre de la rentabilidad emocional, la persistencia de un ethos que no se somete completamente a la lógica mercantil es percibida como una amenaza existencial. El sujeto cínico, como explica Peter Sloterdijk, ya no se indigna: se ríe con un sentido de superioridad que le permite sobrevivir un día más. Pero esa risa no es ligera, es amarga. Es una risa que viene del resentimiento, de saberse incapaz de producir un equivalente, de curar. Festejar la muerte es, entonces, un intento desesperado por eliminar lo que no se puede reemplazar. No puedo superar el hecho de que el Gordo Dan sea médico. Simplemente, no puedo. No es un médico, sino un estudioso desviado de torturador. Un Diddy que nació en el lugar equivocado pero moriría por hacer una freakoff y cagar a palos a Cassie.

Festejar la muerte es, entonces, un intento desesperado por eliminar lo que no se puede reemplazar. No puedo superar el hecho de que el Gordo Dan sea médico.

Tweet

Desde esta perspectiva, Mujica emerge como el típico “muerto incómodo” —ese cuya mera existencia desestabiliza el presente—se vuelve central. Mujica, como Evita, Perón, Chávez o incluso Néstor Kirchner, se transforma en lo que Derrida llama espectro: una figura que no está, pero cuya ausencia acecha por fuerza de sus ideas y si no de sus ideas, de lo que representa. El espectro no puede ser enterrado del todo porque no pertenece ni al presente ni al pasado. Su insistencia es una ontología del retorno que incomoda a los regímenes lineales del tiempo político. El festejo del Gordo Dan no niega la vida sino fracasada en el exorcismo del muerto; la expresión de un deseo frustrado de borrar el pasado sin asumir la responsabilidad de superarlo. No hay superación en el Gordo Dan sino regresión infantil. No hay fertilidad sino impotencia. No hay creatividad sino vergüenza de no poder ser lo Nietzcheano que quiere ser.

Desde esta perspectiva, Mujica emerge como el típico “muerto incómodo” —ese cuya mera existencia desestabiliza el presente—se vuelve central.

Tweet

En este contexto, su posteo no comunica una idea ni construye una verdad: es una cataquesis, un uso impropio del lenguaje que sustituye lo que no se puede nombrar. Festejar la muerte de Mujica permite decir lo indecible: que en su régimen de afectos exilia a la ética. Pero esa catarsis es precaria. Su eficacia es efímera, porque el espectro de Mujica—como el de cualquier figura que vivió según reglas distintas—sigue rondando y cuanto mas se lo profana, mas vigente lo vuelve. No por lo que fue, sino por lo que recuerda: que otro mundo fue posible. Y que Desde esta perspectiva, Mujica emerge como el típico “muerto incómodo” —ese cuya mera existencia desestabiliza el presente—se vuelve central.

La medicina es una ética del cuidado. Pero en el caso del Gordo Dan, esa ética se ha invertido: el médico se ha reconvertido en tanatologo, y el juramento hipocrático en espectáculo algorítmico.

Tweet

Que sea precisamente un médico quien emita esta sentencia festiva me acecha. Perdón que me repita. Porque en su formación, el médico no sólo se entrena para preservar la vida, sino para sostenerla incluso cuando ya no promete productividad, utilidad o eficacia. La medicina es, en última instancia, una ética del cuidado. Pero en el caso del Gordo Dan, esa ética se ha invertido: el saber médico se ha reconvertido en tanatología, y el juramento hipocrático en espectáculo algorítmico. Entre el ghost in the machine y el espectro, ya qué son los fantasmas sino recuerdo, esa memoria no muere, se demora. Y a quienes se apuran a celebrar su muerte, les devuelve —como advertía Derrida— la mirada de lo no resuelto. Hay algo peor que ser un torturador entrenado y fracasado por no animarse a dar el paso de la carne?

Entre el ghost in the machine y el espectro, ya qué son los fantasmas sino recuerdo, esa memoria no muere, se demora. Y a quienes se apuran a celebrar su muerte, les devuelve —como advertía Derrida— la mirada de lo no resuelto.

Tweet

‘Celebrating Death as Political Gesture: Gordo Dan, Pepe Mujica, and the Necropolitics of Cynicism’ (ENG)

On May 14, shortly after the death of José “Pepe” Mujica was confirmed, the Argentine influencer Gordo Dan — a trained physician and rising figure in the libertarian cybersphere — posted a brief message on X: “One less.” The post, celebrated with thousands of likes, was not merely an expression of political disagreement, nor even of ideological contempt: it was a celebration of death. What does it mean for a doctor — someone trained to preserve life — to publicly celebrate the death of a former president whose trajectory was marked by sobriety, resistance, and a republican ethic free of cynicism? The question is not a moral one, but a theoretical one: what kind of political subjectivity is produced when the death of the other — not their defeat, not their error, but their disappearance — becomes a shared source of enjoyment?

On May 14, shortly after the death of José “Pepe” Mujica was confirmed, the Argentine influencer Gordo Dan — a trained physician and rising figure in the libertarian cybersphere — posted a brief message on X: “One less.”

Tweet

What is celebrated in Mujica’s death is not merely the biological end of an individual, but the dismantling of a figure who, even from his marginal institutional position, represented a symbolic threat to the new affective order of late neoliberalism. That order requires not allegiance but rejection; it does not build the future but feeds on the destruction of the past. Gordo Dan’s celebration is not a marginal gesture but a symptom of what Achille Mbembe calls necropolitics: a form of governance in which sovereignty is exercised not by guaranteeing life, but by deciding who deserves to die, be forgotten, or be degraded.

Gordo Dan’s celebration is not a marginal gesture but what Achille Mbembe calls necropolitics: a form of governance in which sovereignty is exercised not by guaranteeing life, but by deciding who deserves to be degraded.

Tweet

In this framework, Mujica’s figure becomes intolerable not because of his power but because of his ethical residue. His austerity is not effective, but exemplary. His biography is not heroic, but resilient. In a system that has emptied symbolic substance in the name of emotional profitability, the persistence of an ethos that does not fully submit to market logic is perceived as an existential threat. The cynical subject, as Peter Sloterdijk explains, no longer expresses outrage — he laughs with superiority. But that laugh is not light, it is bitter. It comes from resentment, from the awareness of being unable to produce a symbolic equivalent. Celebrating death is, then, a desperate attempt to eliminate what cannot be replaced.

The cynical subject, as Peter Sloterdijk explains, no longer expresses outrage — he laughs with superiority. But that laugh is not light, it is bitter. It comes from resentment.

Tweet

From this perspective, the figure of the “uncomfortable dead” — one whose mere existence destabilizes the present — becomes central. Mujica, like Perón, Chávez, or even Néstor Kirchner, becomes what Jacques Derrida conceptualizes as a specter: a figure who is not here, but whose absence persists. The specter cannot be fully buried because it belongs neither to the present nor to the past. Its persistence is what Derrida calls hauntology: an ontology of return that unsettles the linear regimes of political time. Celebration, then, is not just the denial of life but a failed exorcism — the expression of a frustrated desire to erase the past without assuming the responsibility of overcoming it.

From this perspective, the figure of the “uncomfortable dead” — one whose mere existence destabilises the present — becomes central. Mujica becomes what Derrida conceptualizes as a specter: a figure who is not here, but whose absence haunts.

Tweet

In this context, Gordo Dan’s post does not communicate an idea or construct a truth: it is a catachresis, in the sense used by Ross Chambers — an improper use of language that substitutes for what cannot be named. Celebrating Mujica’s death allows the unspeakable to be said: that in the neoliberal regime of affect, ethics has no place. But that catharsis is precarious. Its efficacy is fleeting, because Mujica’s specter — like that of any figure who lived by different rules — continues to linger. Not for what he was, but for what he reminds us of: that another world was possible. And the joy of the executioner, no matter how many likes it gathers, will not bury the question that returns like an echo: why so much hatred for someone who did not hate?

The joy of the executioner, no matter how many likes it gathers, will not bury the question that returns like an echo: why so much hatred for someone who did not hate?

Tweet

That it was a doctor who issued this celebratory sentence is no minor detail. Because in their training, doctors are taught not only to preserve life but to sustain it even when it promises no productivity, utility, or efficiency. Medicine is, ultimately, an ethics of care. But in Gordo Dan’s case, that ethic has been inverted: medical knowledge has been reconfigured into necropolitical expertise, and the Hippocratic oath into algorithmic spectacle. What is being celebrated is not the fall of an adversary but the symbolic extinction of an intolerable difference. Mujica dies, and with him there is an attempt to bury something that survives: the memory that another politics was possible. But like all specters, that memory does not die — it lingers. And to those who rush to celebrate his death, it returns — as Derrida warned — with the gaze of what remains unresolved.

What el Gordo Dan celebrates is not the fall of an adversary but the symbolic extinction of an intolerable difference.

Tweet

Deja una respuesta