Scroll Down for the English Version

Introducción

En las tragedias griegas, el poder femenino no es simplemente lo opuesto al masculino, sino su reverso más inquietante: su sombra, su exceso, su forma envenenada. Hay tres figuras paradigmáticas de ese poder trágico: Clitemnestra, Medea y Antígona. Las tres desobedecen, pero no de la misma manera. Las tres desafían el orden patriarcal, pero no con los mismos fines. Si vamos a hablar de Cristina Fernández de Kirchner —como lo hace Javier Grossman en el correo que motiva este texto— conviene recordar quiénes fueron esas mujeres y por qué la comparación es inevitable… pero también limitada.

Clitemnestra es la esposa de Agamenón. Mientras él está en la guerra de Troya, sacrifica a su hija para obtener viento favorable en nombre de la patria. Clitemnestra no lo perdona. Lo espera durante diez años y, cuando vuelve, lo asesina en la bañera con ayuda de su amante Egisto. Clitemnestra gobierna Micenas con mano firme. No representa la justicia sino la venganza, el cálculo, la administración de una herida como fundamento del poder.

Medea es la extranjera, la hechicera que traiciona a su pueblo por amor a Jasón. Pero cuando él la abandona por una princesa griega, Medea enloquece y lo castiga de forma radical: asesina a sus propios hijos. No por locura, sino para impedir que él los use como capital simbólico. Su violencia no es impulsiva, sino estratégica. Medea es el reverso de la maternidad: la mujer que, por no aceptar la traición del orden masculino, destruye hasta el símbolo mismo de su función biológica.

Antígona, en cambio, desobedece sin cálculo. Entierra a su hermano muerto contra la orden del rey. No gobierna, no manipula, no se venga. Muere sola, sin espectáculo, sin descendencia. Su desobediencia es ética y silenciosa: se inscribe en otra lógica, la del límite, la del duelo, la del derecho no escrito.

Cristina no es Antígona. No hay en ella ni humildad ante lo sagrado, ni renuncia ante el poder. Pero sí hay —y en lo que Javier Grossman celebra— trazos de Clitemnestra, la que nunca se fue porque no perdona, y de Medea, la que destruye lo que engendró para no irse.

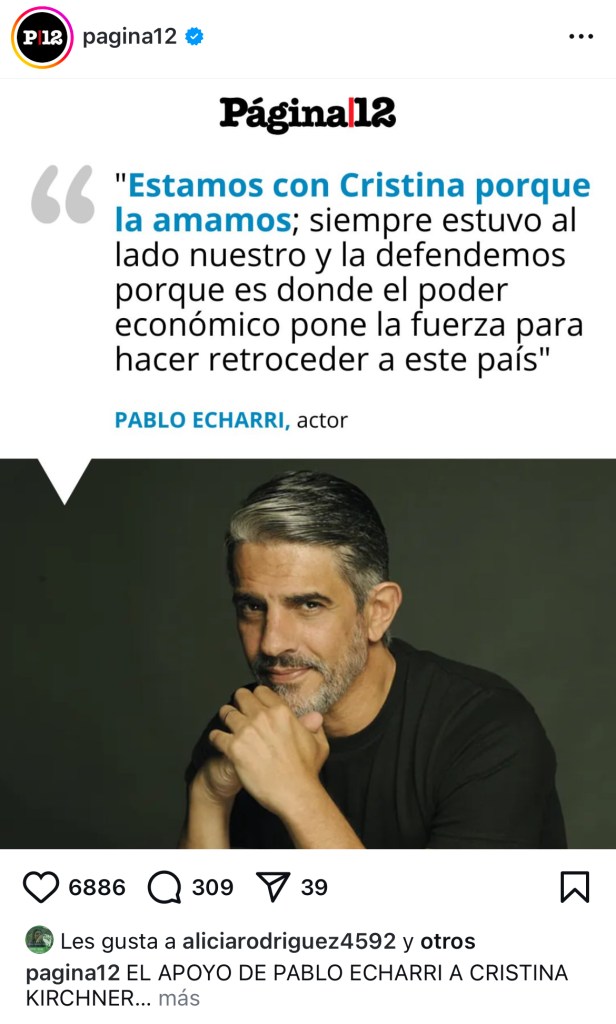

Tweet

Cristina no es Antígona. No lo fue nunca. No hay en ella ni humildad ante lo sagrado, ni renuncia ante el poder, ni voluntad de desaparecer. Pero sí hay en ella —y en lo que Javier Grossman celebra— trazos evidentes de Clitemnestra, la que nunca se fue porque no perdona, y de Medea, la que destruye lo que engendró para no entregar su legado. Cristina se presenta como madre del pueblo, pero es una madre que guarda rencor, que no transmite herencia, que destruye el campo que dice cuidar por miedo a que alguien lo ocupe mejor que ella. No es una víctima del orden patriarcal: es una administradora de su retorno deformado.

Cristina no es una víctima del orden patriarcal: es una administradora de su retorno deformado.

Tweet

Este texto es una respuesta a Grossman, pero sobre todo es una advertencia. Porque cuando la política se convierte en tragedia sin conciencia, lo que queda no es la catarsis, sino el espanto.

Cristina, mito fallido y estrategia fallada

Digo esto a modo de respuesta a un correo que recibí hace pocos días de parte de Javier Grossman, en reacción a mi post anterior Cristina, la loca útil. En su email, Grossman despliega una defensa enfática de la expresidenta, exaltando su figura como mito viviente, mujer resiliente y estratega lúcida en un escenario político devastado. Pero lo que Grossman presenta como virtudes políticas, yo lo leo como síntomas patológicos de una cultura del poder incapaz de dejar de girar en torno a su narcisismo herido.

Grossman no es un actor menor en esta historia. Fue presidente del Instituto Nacional del Teatro entre 2003 y 2006, director general de Industrias Culturales y, sobre todo, principal organizador del Bicentenario de 2010, ese gigantesco acto de fe estética con que el kirchnerismo buscó consolidar su mito. Hombre clave en la articulación entre política, espectáculo y memoria, Grossman encarna como pocos la lógica del progresismo ornamental: la patria como puesta en escena, y el mito como forma de gobierno. Desde ese lugar me escribe —y desde ese lugar le respondo.

El cuerpo de la mujer poderosa

Grossman escribe: “Cristina no se va porque insiste. Porque pone el cuerpo en un país que le exige a las mujeres poderosas volverse mito o desaparecer.”

Esto es parcialmente cierto, pero muy tramposo. En la cultura argentina, la mujer que accede al poder lo hace a menudo a condición de entrar en combustión: volverse loca, suicidarse, retirarse humillada. Pero Grossman omite un dato clave: esa lógica también fue reproducida por el propio kirchnerismo, que encumbró a figuras como Hebe de Bonafini y Estela de Carlotto hasta volverlas intocables, simbólicamente blindadas, pero a la vez reducidas a un rol ceremonial dentro del relato estatal. La visibilidad que obtuvieron fue indiscutible, pero también las convirtió en garantes de una narrativa que el poder central instrumentalizó hasta la fetichización. Bonafini fue usada como escudo moral incluso cuando su entorno estaba envuelto en escándalos de corrupción; Carlotto, más moderada, quedó confinada a la administración institucional de una memoria pública cada vez más blanqueada y excluyente.

En la cultura argentina, la mujer que accede al poder de suicidarse o, retirarse humillada. Pero eso fue reproducido por el propio kirchnerismo, que encumbró a Bonafini y Carlotto hasta volverlas intocables, blindadas, aunue reducidas a un rol ceremonial dentro del relato estatal.

Tweet

Cristina no sufrió esa violencia simbólica: la centralizó y la utilizó como método de control. Mientras el sistema patriarcal exigía locura o retiro a las mujeres poderosas, Cristina construyó su figura a través de la administración del sacrificio ajeno. No desafió ese mandato: lo redirigió hacia otras mujeres. Por eso no puede ocupar el lugar de Storni ni de Pizarnik: no es mártir, ni marginal, ni subversiva, sino curadora de un canon político funcional a su propia supervivencia.

Cristina no puede ocupar el lugar de Storni ni de Pizarnik: no es mártir, ni marginal, ni subversiva, sino curadora de un canon político funcional a ella.

Tweet

Espectáculo y vacío

Grossman también afirma: “La escena del balcón no es el epílogo de un delirio: es una intervención en el campo simbólico. Es una forma de decir ‘aún estoy’.”

Cuando Cristina aparece como espectáculo, no interrumpe el orden simbólico de Milei: lo consolida.

Tweet

Una señora bailando en un balcón no es, en sí, una intervención estética ni política. Es un berrinche performático de quien aún no entiende que no se le debe nada. El kirchnerismo ha sido experto en transformar el Estado en escenario, la militancia en coreografía, el luto en escenografía. Pero esa espectacularización no transforma el mundo, lo empobrece. Cuando Cristina aparece como espectáculo, no interrumpe el orden simbólico de Milei: lo consolida.

Más aún, sostiene Grossman: “Cristina elige no irse (…) porque retirarse en este momento es dejar el campo vacío. Y el vacío no es neutro.” Esta es la gran falacia argentina. No sueltan la manija por miedo a que los que vengan no repartan las prebendas. Cristina no dejó crecer a nadie: ni a los suyos, ni a los otros. Lo que quedó fue un campo seco donde floreció… Milei.

Más aún, sostiene Grossman: “Cristina elige no irse (…) porque retirarse en este momento es dejar el campo vacío. Y el vacío no es neutro.” Esta es la gran falacia argentina. No sueltan la manija por miedo a que los que vengan los dejen afuera.

Tweet

¿Barro o cinismo?

“Muchos de los que hoy piden ‘renovación’ no ofrecen más que cinismo”, dice Grossman. Yo, que me eduqué desde abajo, que sufrí estigmas y rechazos, no desprecio el barro. Pero no acepto que me lo vendan como autenticidad mientras lo usan para justificar privilegios. Hoy, el barro no es raíz popular: es aislamiento, deuda, hambre. Cristina y su aparato convirtieron el barro en folclore legitimador de su miseria moral.

Pactos, derechos y fetiches

Cristina pactó su prisión. Pactó con Macri. Pactó con Milei. Y como todo lo que construyó fue para sí misma, hoy no tiene nada que negociar. El peronismo está en ruinas, y el resultado de esos pactos es Milei, que no respeta ni la firma.

Cristina pactó su prisión. Pactó con Macri. Pactó con Milei. Y como todo lo que construyó fue para sí misma, hoy no tiene nada que negociar. El peronismo está en ruinas, y el resultado de esos pactos es Milei,

Tweet

Cuando Grossman dice: “Cristina sostuvo derechos (…) y no baila sola”, yo recuerdo que los derechos no son acumulativos ni eternos. No se declaran: se sostienen con poder real. El kirchnerismo construyó culto, no ciudadanía. Y convirtió al movimiento de derechos humanos en una nobleza de sangre donde la moral nacional quedó en manos de apellidos y parentescos.

El apocalipsis no es una metáfora

Milei se abraza con Netanyahu el mismo día que Israel ataca Irán. El Mossad no nos va a salvar. La neutralidad no existe. Somos carne de cañón del nuevo orden multipolar. Y Cristina, bailando en un balcón, no es resistencia. Es negación de su propia monstruosidad. Milei no es su enemigo: es su descendencia simbólica.

El monstruo no es Máximo. Ni Florencia. El monstruo es Milei. Y el padre es Macri. Pero la madre fue y sigue siendo ella.

Cristina, Mother of the Apocalyptic Monster: Closer to Medea and Clytemnestra than to Antigone

Introduction

In Greek tragedy, female power is not simply the opposite of male power—it is its most unsettling reverse: its shadow, its excess, its poisoned form. Three paradigmatic figures embody this tragic power: Clytemnestra, Medea, and Antigone. All three disobey, but not in the same way. All three challenge the patriarchal order, but not with the same ends. If we are to speak of Cristina Fernández de Kirchner—as Javier Grossman does in the email that prompted this text—it’s worth remembering who these women were, and why the comparison is inevitable… but also limited.

Clytemnestra is the wife of Agamemnon. While he is away at the Trojan War, he sacrifices their daughter to secure favorable winds in the name of the homeland. Clytemnestra never forgives him. She waits ten years, and when he returns, she kills him in the bath with the help of her lover, Aegisthus. Clytemnestra rules Mycenae with a firm hand. She does not represent justice but revenge, calculation, the administration of a wound as the foundation of power.

Medea is the foreigner, the sorceress who betrays her own people for love of Jason. But when he abandons her for a Greek princess, Medea goes mad and punishes him radically: she kills their own children. Not out of madness, but to prevent him from using them as symbolic capital. Her violence is not impulsive but strategic. Medea is the reversal of maternity: the woman who, unwilling to accept the betrayal of the male order, destroys even the symbol of her biological function.

Antigone, by contrast, disobeys without calculation. She buries her brother against the king’s orders. She does not rule, does not manipulate, does not take revenge. She dies alone, without spectacle, without descendants. Her disobedience is ethical and silent: it belongs to another logic—the logic of limits, of mourning, of unwritten law.

Cristina is not Antigone. She never was. There is in her no humility before the sacred, no renunciation of power, no willingness to disappear. But in her—and in what Grossman celebrates—there are clear traces of Clytemnestra, who never left because she never forgave, and Medea, who destroys what she gave birth to rather than relinquish her legacy. Cristina presents herself as mother of the people, but she is a mother who holds grudges, who withholds inheritance, who destroys the field she claims to care for out of fear someone might occupy it better. She is not a victim of the patriarchal order: she is the administrator of its distorted return.

Cristina presents herself as mother of the people, but she is a mother who holds grudges, who withholds inheritance, who destroys the field she claims to care for out of fear someone might occupy it better.

Tweet

This text is a response to Grossman, but above all, it is a warning. Because when politics turns into tragedy without awareness, what remains is not catharsis, but horror.

Cristina, failed myth and failed strategy

I write this in response to an email I received a few days ago from Javier Grossman, reacting to my earlier post Cristina, the Useful Madwoman. In his message, Grossman offers a spirited defense of the former president, exalting her as a living myth, a resilient woman, and a lucid strategist in a politically devastated landscape. But what Grossman presents as political virtues, I read as pathological symptoms of a culture of power unable to stop orbiting its wounded narcissism.

Grossman is no minor figure in this story. He was President of the National Theatre Institute from 2003 to 2006, Director of Cultural Industries, and most notably, chief architect of Argentina’s 2010 Bicentennial—that massive act of aesthetic faith through which Kirchnerism sought to consolidate its myth. A key figure in the articulation of politics, spectacle, and memory, Grossman embodies like few others the logic of ornamental progressivism: the nation as performance, and myth as a form of governance. It is from that place that he writes to me—and from that place that I respond.

The body of powerful women

Grossman writes: “Cristina doesn’t leave because she insists. Because she puts her body forward in a country that demands powerful women either become myth or disappear.”

This is partially true, but deeply misleading. In Argentine culture, women who attain power often do so on the condition that they combust: they must go mad, commit suicide, or retire in humiliation. But Grossman omits a key fact: this logic was also reproduced by Kirchnerism itself, which elevated figures like Hebe de Bonafini and Estela de Carlotto to untouchable status, symbolically shielded, but also reduced to ceremonial roles within the state narrative. Their visibility was undeniable, but they were turned into guarantors of a story that the central power fetishized and instrumentalized. Bonafini was used as a moral shield even when those around her were engulfed in corruption scandals; Carlotto, more moderate, was confined to managing an increasingly whitewashed and exclusionary public memory.

Bonafini was used as a moral shield even when those around her were engulfed in corruption scandals; Carlotto, more moderate, was confined to managing an increasingly whitewashed and exclusionary public memory.

Tweet

Cristina did not suffer that symbolic violence: she centralized it and used it as a tool of control. While the patriarchal system demands madness or retreat from powerful women, Cristina built her figure by administering others’ sacrifices. She didn’t defy that mandate: she redirected it onto other women. That’s why she cannot occupy the place of Storni or Pizarnik: she is neither martyr, nor marginal, nor subversive, but a curator of a political canon tailored to her own survival.

Spectacle and emptiness

Grossman also claims: “The scene on the balcony is not the epilogue of a delusion: it’s an intervention in the symbolic field. A way of saying ‘I’m still here.’”

A woman dancing on a balcony is not, in itself, an aesthetic or political intervention. It’s the tantrum of a spoiled señora who still believes she’s owed something. Kirchnerism has mastered the transformation of the state into a stage, militancy into choreography, and mourning into set design. But that spectacularization does not transform the world—it impoverishes it. When Cristina appears as spectacle, she does not disrupt Milei’s symbolic order: she confirms it. The battle becomes theater, and theater always favors the most grotesque clown.

Grossman continues: “Cristina chooses not to leave (…) because leaving now would leave the field empty. And the void is not neutral.”

This is Argentina’s great fallacy. They won’t let go of the wheel—not out of historical responsibility, but out of fear that whoever comes next won’t include them in the spoils. Cristina let no one grow—not her own, not the others. What remained was a barren field where… Milei flourished.

Mud or cynicism?

“Many who call for ‘renewal’ today offer nothing but cynicism,” says Grossman.

I, who was educated from the bottom, who faced stigma and rejection, do not despise the mud. But I do despise being sold mud as authenticity when it’s used to justify privilege. Today, mud is no longer “popular roots”: it is isolation, debt, hunger. Cristina and her apparatus turned mud into folklore legitimizing their moral decay.

Pacts, rights, and fetishes

Cristina negotiated her own prison. She made deals with Macri. She made deals with Milei. And, as expected, they screwed her over. Macri doesn’t honor deals. Milei doesn’t understand them. And now she has nothing left to negotiate. The Peronist movement lies in ruins. The empty plaza is her masterwork.

Cristina negotiated her own prison. She made deals with Macri. She made deals with Milei. And, as expected, they screwed her over. Macri doesn’t honor deals. Milei doesn’t understand them.

Tweet

When Grossman writes: “Cristina upheld rights (…) and she’s not dancing alone,” I must remind him that rights are not cumulative, not eternal, and not privately owned. Kirchnerism believed that declaring rights was enough to preserve them. It didn’t build power to defend them: it built cult. And cults require martyrs, not citizens. Cristina never understood power beyond her own survival. She transformed the human rights movement—already exclusionary and whitened—into a blood nobility, where moral authority was reserved for family names and inherited pain.

The apocalypse is not a metaphor

Milei embraces Netanyahu on the very day Israel bombs Iran. Mossad will not save us. Neutrality is an illusion. We are cannon fodder in the new multipolar order. And Cristina, dancing on a balcony, is not resistance. She is denial of her own monstrosity. Milei is not her enemy: he is her symbolic child. The monster is not Máximo. Nor Florencia.

The monster is Milei. The father is Macri. But the mother was—and remains—her.

Deja una respuesta