SCROLL DOWN FOR THE ENGLISH VERSION

Ayer, en la red X, vi dos imágenes que, aunque aparentemente inconexas, condensan el núcleo paranoico del actual régimen argentino. La primera fue un video publicado por la cuenta @RaceAwakening en el que un niño blanco —rubio, ojos celestes, piel de porcelana— era indicado como emblema de la argentinidad. No se trataba solo de un montaje nostálgico, sino de una afirmación política: ese niño no representa una infancia cualquiera, sino una forma ideal de ciudadanía: el patron de estancia comprada con oro Nazi. El argentino verdadero es, en esa imagen, blanco, infantilizado, angelical, desprovisto de mezcla y de historia. Un niño, no un sujeto.

Ayer, en la red X, vi dos imágenes que, aunque aparentemente inconexas, condensan el núcleo paranoico del actual régimen argentino.

Tweet

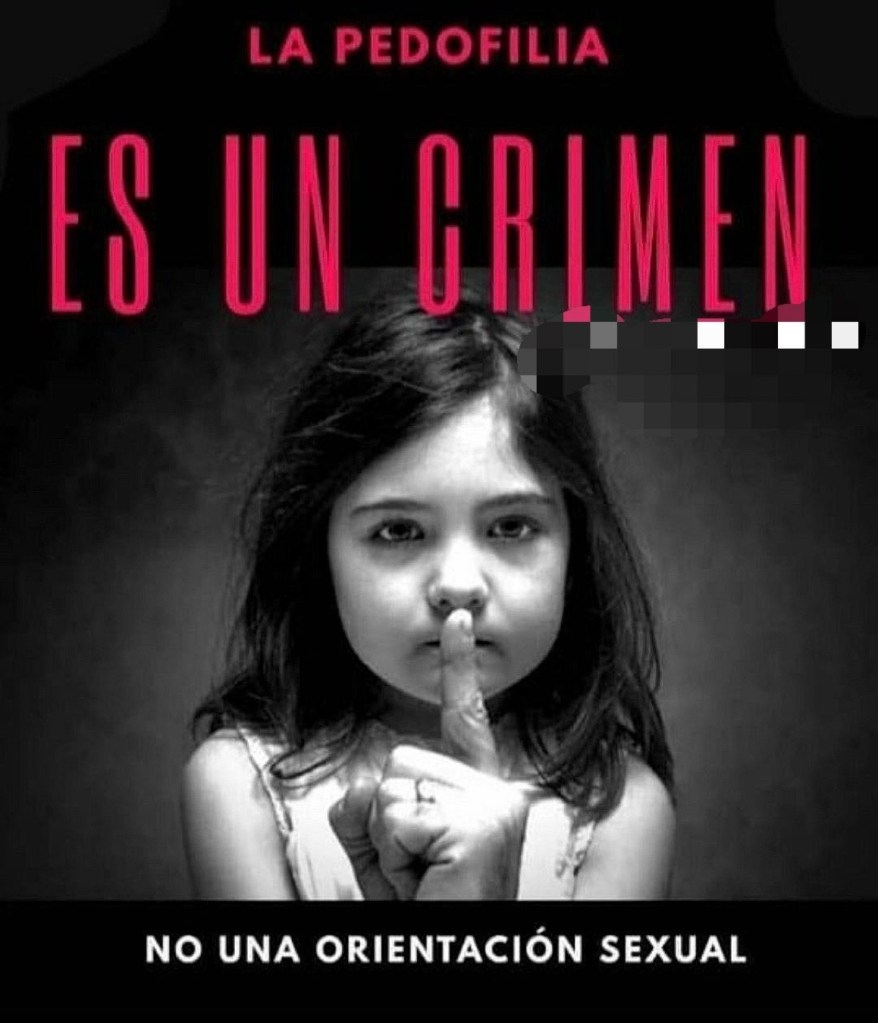

La segunda imagen circuló como parte de una supuesta campaña contra la pedofilia y fue difundida por el periodista Esteban Trebucq, vocero oficioso del gobierno de Javier Milei. En ella se ve a una niña con el gesto de “hacer silencio” mientras un dedo masculino —venoso, adulto, erguido— se posa sobre su boca. Para peor, el dedo tiene una punta peneana. El mensaje, escrito en mayúsculas: “LA PEDOFILIA ES UN CRIMEN, NO UNA ORIENTACIÓN SEXUAL”. Nadie en su sano juicio podría oponerse a esa afirmación. La pedofilia es un crimen. Punto. Pero lo verdaderamente inquietante es la forma visual en que se elige representarla: no desde la denuncia explícita, sino desde una iconografía cargada de ambigüedad sexual, donde el dedo que ordena callar encarna el mismo poder que supuestamente se busca condenar.

El periodista Esteban Trebucq, vocero oficioso del gobierno de Milei publicó la imagen de una niña con el gesto de “hacer silencio” mientras un dedo masculino —venoso, adulto, peneano— se posa sobre su boca.

Tweet

Lo que estas dos imágenes comparten no es el contenido sino la función: proyectar sobre los cuerpos infantiles la fantasía restauradora de una masculinidad rota. En un país donde el padre ya no representa, donde la ley se volvió meme, donde el Estado se ha vaciado de toda autoridad simbólica, la ultraderecha encuentra en el cuerpo infantil —ya sea blanqueado, ya sea silenciado (la niña no es rubia, obvio)— un punto de anclaje para rehacer un orden imposible.

En un país donde el padre ya no representa, donde el Estado se ha vaciado de toda autoridad simbólica, la ultraderecha encuentra en el cuerpo infantil — blanqueado, o silenciado — un punto de anclaje.

Tweet

Ese niño blanco no es una criatura real: es un avatar de pureza racial, una promesa eugenésica, una nostalgia de nación sin mezcla. Y esa niña con el dedo erecto en la boca no es una víctima protegida: es una puesta en escena sacrificial, un soporte para el sadismo moralista del patriarcado que ya no se atreve a nombrar su propio deseo.

Ese niño blanco no es una criatura real: es un avatar de pureza racial, una promesa eugenésica, una nostalgia de nación sin mezcla.

Tweet

Yuyito González, referente evangelista del mileísmo, dijo recientemente que se “horrorizó por las cosas que vio”, sin aclarar qué vio exactamente. No hace falta. Lo no dicho cumple mejor su función: cada quien proyecta su propio espanto. Esa es la pedagogía afectiva del fascismo: mostrar lo justo para excitar el castigo, omitir lo suficiente para permitir la fantasía.

La niña con el dedo erecto en la boca no es una víctima protegida: es una puesta en escena sacrificial, un soporte para el sadismo moralista de Trabucq.

Tweet

Todo esto no es escándalo mediático: es ideología. Es una política visual del miedo a través de un deseo perverso. Una estética de la restitución viril. Un régimen afectivo que encuentra en el niño blanco y en la niña silenciada el cuerpo político perfecto para encubrir su misoginia, su racismo y su pulsión de exterminio.

La espantosa historia argentina

Todo esto —el niño purificado, la niña callada— no ocurre en el vacío. Ocurre sobre un fondo específico: una historia nacional que nunca fue plenamente contada. Una historia que, en lugar de ser narrada, fue desplazada hacia el espectáculo, el mito o la negación. Una historia que, como escribió Silvia Schwarzböck, se volvió “una pantalla negra”.

En Los espantos, Schwarzböck define la posdictadura como un régimen de visibilidad sin discurso: “lo que no puede decirse de la dictadura es lo que sí puede verse”. La frase es brutal. En Argentina no se niega el horror: se lo estetiza, se lo encapsula, se lo vuelve imagen inofensiva. En esto Silvia y mi Historia a Contrapelo del Arte Argentino (Sudamericana, 2021) coincidimos totalmente. El torturador deja de ser un sujeto histórico y pasa a ser un personaje: un villano sadomasoquista, casi de ficción. Igual que los nazis en Hollywood. La maquinaria del exterminio se vuelve decorado.

Esa “pantalla negra” a la que se refiere Schwarzböck —imagen muda, opaca, irrepresentable— es lo que queda cuando el relato fracasa. Cuando la palabra no alcanza. Cuando la memoria se transforma en forma vacía. De ahí que la figura del niño blanco de @RaceAwakening funcione como reemplazo: es una imagen contra el espanto, un intento de restaurar inocencia allí donde hubo terror. Un niño sin historia es el mejor antídoto contra el archivo.

Leopoldo Brizuela lo intuyó en su premiada novela (Alfaguara) titulada Una misma noche, cuando escribió: “Quizá sólo la literatura podría perdonar. La literatura, ese lector futuro”. Pero ese lector futuro nunca llega. O si llega, no quiere saber. En esa novela —un ajuste de cuentas con la propia cobardía durante la dictadura—, el narrador asume que no basta con haber visto: hay que poder contarlo. Y contar, en Argentina, es siempre un gesto interrumpido, vacilante, marcado por el miedo de decir demasiado o demasiado poco.

En un momento clave, Brizuela escribe: “Para contar la historia… es preciso ser víctima. Del presente. O de su memoria”. Y es ahí donde el presente vuelve a cobrar sentido: en el modo en que las nuevas formas de fascismo reactivan los traumas del pasado sin nombrarlos, sin explicarlos, sin asumirlos. El niño blanco y la niña silenciada son, justamente, las figuras que emergen cuando ya no se puede o no se quiere narrar lo verdaderamente intolerable: el pacto de blanquitud que fundó el país, el exterminio indígena, la violencia sexual estructural, la complicidad de las clases medias con el terror.

Si el arte de la posdictadura consistió en representar el espanto sin hablar directamente del espanto —una coreografía de gestos elípticos, metáforas, abstracciones—, lo que estamos viendo hoy es su reverso brutal: una hiperrepresentación que borra, una denuncia que erotiza, una inocencia que encubre. La Argentina mileísta no niega el pasado: lo sustituye por una estética de redención infantil, blanca, muda (en caso que no sea tan blanca).

La Argentina mileísta no niega el pasado: lo sustituye por una estética de redención infantil, blanca, muda (en caso que no sea tan blanca).

Tweet

Y como todo relato reaccionario, este también tiene su estética: tonos lavados, sonrisas congeladas, miradas limpias, tipografías firmes. El orden no necesita argumento si tiene imagen.

El aristócrata queer y la eugenesia nacional

El niño blanco que hoy circula como emblema de argentinidad no es una novedad. Es una reencarnación. Su linaje puede trazarse hasta las elites ilustradas de fines del siglo XIX, cuando las clases dirigentes —al tiempo que fundaban bibliotecas y ferrocarriles— diseñaban también un futuro racialmente purificado para el país. Fue entonces cuando se consolidó la ecuación entre progreso y blanquitud, civilización y control del deseo, república y eugenesia.

Una figura clave de ese momento es Carlos Octavio Bunge, sociólogo, jurista, educador y, como muestra Joseph M. Pierce en Argentine Intimacies, aristócrata queer. Bunge fue parte de una familia de alta sociedad —los Bunge— y uno de los cerebros ideológicos del nacionalismo positivista argentino. Vestía como un dandy, escribía con pasión decadentista y frecuentaba círculos donde la sensibilidad masculina divergía del ideal viril hegemónico. Pero esa ambigüedad de género que Pierce idealiza, no lo alejó del poder. Al contrario: lo reforzó como estratega de una nación que se soñaba blanca, ordenada y masculina.

Pierce recupera esa tensión con aparente lucidez, lo que plantea la pregunta de por qué le presta tanta atención el academico queer indigena: “Carlos Octavio Bunge, dandy finisecular, fue también autor de proyectos que justificarían la eliminación étnica de pueblos indígenas en nombre del progreso.” En su libro Nuestra América (1926), Bunge desarrolla una visión racializada del continente, defendiendo que la Argentina debía preservarse mediante la incorporación de inmigrantes “deseables” —europeos, blancos, disciplinados— y la exclusión de los “degenerados”, concepto heredado directamente de la retórica eugenésica europea.

En su libro Nuestra América (1926), Bunge desarrolla una visión racializada del continente, defendiendo que la Argentina debía preservarse mediante la incorporación de inmigrantes “deseables” .

Tweet

Lo fascinante y perturbador de la figura de Bunge es que encarna la complicidad estructural entre disidencia sexual y blanqueamiento ideológico. En lugar de ser un outsider, su sensibilidad queer le sirvió para ejercer como curador estético del nuevo cuerpo nacional: más blanco, más ordenado, más racional. Bunge no fue una víctima del sistema: fue su arquitecto. Su legado —que mezcla pedagogía, racismo científico y erotismo de elite— aún palpita en las formas contemporáneas del autoritarismo ilustrado que hoy vemos reaparecer bajo formas tecnológicas, higiénicas y meritocráticas.

Pierce romantiza la desviación. No toda rareza es disidencia, y no toda disidencia desafía el poder. A veces, el desvío sirve para renovar la norma, para rediseñarla, para volverla aún más eficaz. La figura del aristócrata queer no rompe el pacto social: lo embellece. Lo vuelve deseable. La genealogía de nuestra eugenesia nacional no es, entonces, puramente médica ni policial. Es también estética. Es también afectiva. Es también sexual. El país que se pensó blanco se diseñó desde el deseo. Y ese deseo no siempre fue heterosexual, pero sí fue profundamente normativo: buscaba controlar el mestizaje, jerarquizar los cuerpos, y, sobre todo, convertir la educación y la ciencia en herramientas de filtrado social.

El niño blanco de @RaceAwakening es hijo directo de esa utopía. No nace del pueblo, no nace del barro. Nace del archivo, de la curaduría racial que las elites ilustradas tejieron durante décadas. Y como su antepasado Bunge, ese niño tampoco tiene deseo: su función es representar una forma ideal de lo humano que no incluye ni mezcla ni erotismo. Es el ícono perfecto del nacionalismo purificador: sin historia, sin conflicto, sin mancha.

En la Argentina, la figura del cadete —militar, policial o penitenciario— funciona como máquina de purificación social. Cada tanto, el sistema cobra vidas.

Tweet

Cadetes, purificación y pedagogía del dolor

Si el niño blanco es la imagen terminal del ciudadano ideal, el cadete argentino es su fase de transición brutal. No es todavía ese cuerpo pulido, pero ya no es el cuerpo mestizo, popular, fuera de control. Es un cuerpo en formación: corregido, expuesto al dolor, redirigido hacia la obediencia. En la Argentina, la figura del cadete —militar, policial o penitenciario— funciona como máquina de purificación social. Cada tanto, el sistema cobra vidas. Y nunca parecen importar demasiado.

Los casos se acumularon durante decadas: cadetes muertos de deshidratación, asfixiados por exceso de ejercicio, víctimas de golpizas colectivas en entrenamientos disfrazados de “formación de carácter”. El discurso oficial hablaba de accidentes, de “excesos individuales”, de fallos puntuales. Pero en realidad, lo que estos episodios revelaban es un régimen sistemático de construcción del cuerpo masculino nacional: un cuerpo blanco, fuerte, heteronormado, impermeable al deseo, útil para el castigo.

La pedagogía del dolor, hoy, sigue estructurando estas instituciones. Es una forma actualizada de eugenesia. Ya no se trata de medir cráneos ni de aplicar teorías raciales sino de forjar cuerpos a través del sufrimiento físico como filtro de aptitud moral. Quien aguanta, sobrevive. Quien no, sobra. El ideal no es el ciudadano crítico, ni siquiera el soldado: es el cuerpo que obedece y que castiga. El cuerpo que calla como el de la nena de Trebucq.

Pero como todo dispositivo eugenésico, la escuela de cadetes también estaba cargada de ambivalencias sexuales. El encierro, la desnudez, el control permanente del cuerpo ajeno, las rutinas coreografiadas de vigilancia y castigo, la tensión entre camaradería viril y humillación disciplinaria, producen un campo erótico inconfesable. Lo gay no está ausente. Estaba en el centro mismo del dispositivo. Pero lejos de celebrarse, se transforma en instrumento de control.

Esa ambigüedad no es inocente. La formación del cadete argentino siempre estuvo diseñada para reprimir el deseo y al mismo tiempo servirse de él. Lo que se castiga en público se consume en privado. Lo que se niega en el discurso aparece como ritual. Cada cuerpo marcado por el dolor, cada grito en un entrenamiento, cada muerte naturalizada, fue una forma de restaurar simbólicamente la autoridad perdida del padre, del Estado, de la patria. Los golpes tuvieron su carga erotica que los impulsaba.

En este contexto, la masculinidad no es un dato biológico: es una tecnología política. Una masculinidad que no se hereda, sino que se impone, se prueba, se sufre. Y por eso cada muerto en las escuelas de cadetes, durante décadas, no fue un error: es el precio de mantener la ficción de una nación ordenada por varones fuertes, blancos, obedientes… casi espectrales.

Así como el niño blanco de @RaceAwakening es un ícono sin deseo, el cadete muerto en un entrenamiento se convierte en un mártir sin historia. Ninguno habla. Ninguno recuerda. Ninguno ensucia la pureza del relato.

Aporia y el renacimiento eugenésico en UK y la Europa Alt Right

En uno de los encuentros clave durante su infiltración, el periodista de The Guardian, “Chris” accede a un círculo aún más cerrado de mega-racistas: el de los nuevos ingenieros de la supremacía blanca. Allí conoce a Matthew Frost, exprofesor británico, que bajo el pseudónimo “Matt Archer” dirige Aporia, una revista online dedicada al estudio y difusión de la llamada HBD —“human biodiversity”—, un eufemismo pulido para lo que siempre fue: el intento de jerarquizar vidas según rasgos genéticos.

Un periodista de The Guardian, “Chris” accede a un círculo aún más cerrado de mega-racistas: el de los nuevos ingenieros de la supremacía blanca.

Tweet

Lo notable de Aporia no es su contenido —teorías viejas con ropaje nuevo—, sino su formato. Es una plataforma elegante, con diseño minimalista, tonos azules sobrios, lenguaje técnico y académico. En lugar de panfletos racistas, publica artículos sobre “predicción de inteligencia en embriones”, “diferencias poblacionales en comportamiento” y “colapso demográfico de la civilización europea”. Nada de esvásticas, nada de gritos: solo data, gráficos, algoritmos.

Frost le confiesa a Chris que el proyecto está financiado por un inversor tecnológico estadounidense anónimo. También revela que trabajan junto al danés Emil Kirkegaard, un nombre clave en el nuevo circuito de la eugenesia digital. Kirkegaard administra lo que hoy llaman Human Diversity Foundation, una estructura empresarial registrada en un estado norteamericano con leyes laxas, y heredera directa del infame Pioneer Fund, que en los años treinta financiaba películas de propaganda nazi como Erbkrank.

El danés Emil Kirkegaard, un nombre clave en el nuevo circuito de la eugenesia digital financia el infame Pioneer Fund, que en los años treinta financiaba películas de propaganda nazi como Erbkrank.

Tweet

Pero lo más revelador ocurre en una cena privada. Allí, Frost se entusiasma y deja caer la metáfora: “Esto es como el Pioneer Fund, pero mejorado. Más eficiente, más discreto. Un think tank que opera como startup. Diez tipos, un millón de libras, un algoritmo y una misión”.

¿La misión? Promover lo que él llama “la nueva élite cognitiva”: seleccionar embriones con alto coeficiente intelectual, fomentar la reproducción entre personas con “genes favorables”, desincentivar la natalidad en poblaciones “disfuncionales” y, en un futuro cercano, legislar “remigraciones” de poblaciones racializadas hacia sus países de origen. Todo en nombre del orden, la eficiencia, el futuro.

Promover lo que Kierkegaard llama “la nueva élite cognitiva”: seleccionar embriones con alto coeficiente intelectual, fomentar la reproducción entre personas con “genes favorables”

Tweet

No se trata ya del nazismo clásico. Se trata de un eugenismo 2.0, con planillas de Excel y estética TED Talk. Ya no hace falta convencer a masas ni reeducar pueblos: basta con crear herramientas que normalicen la optimización genética como decisión privada, deseable, incluso afectuosa. Es decir: “No elegimos al más inteligente porque odiemos a los otros, sino porque queremos lo mejor para nuestros hijos”.

En este nuevo régimen, el niño blanco ya no es solo el ícono de la nación pura. Es una inversión genética, un capital afectivo y simbólico que proyecta el futuro de una elite que se cree destinada a sobrevivir la catástrofe global. No es un cuerpo, es un vector de futuro. Un hijo perfecto.

Y el discurso que antes era excluyente se vuelve envolvente. La supremacía ya no se grita: se programa. Ya no es una orden, es una recomendación. No se impone desde el Estado, sino desde las preferencias del consumidor. Así funciona el eugenismo neoliberal: bajo la máscara de la libertad, ofrece un mundo donde algunos cuerpos serán seleccionados, y otros simplemente no llegarán a existir.

Este es el nuevo rostro del fascismo: no el del soldado, sino el del ingeniero. No el del pastor, sino el del inversor. No el del criminal, sino el del padre amoroso que “solo quiere lo mejor”.

El rostro amable de la eugenesia

Si en el siglo XX la eugenesia se impuso desde arriba —con leyes, encierros y campañas públicas de higiene racial—, en el siglo XXI vuelve desde abajo. O desde adentro. Desde la libertad. Desde el afecto. Desde las decisiones “informadas” de individuos responsables. Las formas de gobierno sobre la vida ya no operan prohibiendo, sino optimizando. Ya no se trata de decir quién puede o no puede vivir, sino de ayudar a “elegir mejor”.

Si en el siglo XX la eugenesia se impuso desde arriba —con leyes, encierros y campañas públicas de higiene racial—, en el siglo XXI vuelve desde abajo. O desde adentro. Desde la libertad.

Tweet

Esta es la biociudadanía: un nuevo tipo de subjetividad que gestiona su cuerpo como proyecto, su reproducción como plan estratégico y su salud como inversión. Y advierte que, bajo ese paradigma, la eugenesia no desaparece: se vuelve opción de mercado. Un derecho. Un deber afectivo. Lo vemos en los discursos de salud mental que invitan a “cuidarse”, a “ser la mejor versión de uno mismo”, pero que al mismo tiempo delegan en el individuo la responsabilidad total por su malestar. Lo vemos en las narrativas ecológicas que culpan a la sobrepoblación del colapso planetario y promueven el decrecimiento demográfico como forma de “salvar la Tierra”. Lo vemos en las plataformas de inteligencia artificial que seleccionan embriones según probabilidad de éxito académico. Y lo vemos, también, en la industria de la celebridad genética.

Esta es la biociudadanía: un nuevo tipo de subjetividad que gestiona su cuerpo como proyecto, su reproducción como plan estratégico y su salud como inversión.

Tweet

Hoy, celebridades y empresarios ejercen una eugenesia aspiracional. No se trata de excluir, sino de producir herederos deseables. La élite ya no se define por apellido, sino por ADN. La fascinación por los “hijos perfectos” de influencers, atletas, actrices, científicos, configura una nueva estética de la pureza. La diferencia es que ahora no se impone como norma estatal, sino como aspiración cultural. Y eso la vuelve más difícil de disputar.

La fascinación por los “hijos perfectos” de influencers, atletas, actrices, científicos, configura una nueva estética de la pureza. La diferencia es que ahora no se impone como norma estatal, sino como aspiración cultural.

Tweet

En ese régimen, el niño blanco deja de ser solo un símbolo de la nación: se vuelve un ítem de consumo emocional, una curaduría afectiva del linaje. El deseo de tener un hijo sano, inteligente, normativo, funcional, amable, se convierte en un mandato íntimo, inobjetable. Y con ello se reactiva —sin decirlo— la matriz eugenésica: se descarta la discapacidad, se descarta la diferencia, se descarta lo imprevisible.

El problema no es la tecnología. Es el relato. La historia que nos contamos para justificar por qué elegimos ciertos cuerpos y no otros. Y lo que esa historia revela es que, detrás del discurso del bienestar, se esconde una pulsión antigua: la de ordenar el mundo, limpiar el margen, suprimir lo que no se adapta. Por eso, la nueva eugenesia no necesita campos de concentración. Le basta con una app, una cuenta bancaria y un relato emocionalmente convincente. Lo que antes se hacía por decreto, ahora se hace por amor.

Argentina: laboratorio tardío de un futuro que ya ocurrió

Toda esta arquitectura biopolítica, emocional y tecnocrática —la del “mejoramiento” voluntario, del deseo curado, del niño perfecto— ya está en curso en la Argentina, aunque con el delay melancólico de una cultura que siempre llega tarde a su propia modernización. En el régimen estético de Milei, la eugenesia no es política de Estado (al menos no explícitamente), pero funciona como estética de gobierno: una pedagogía del desprecio y de la purificación afectiva.

En el régimen estético de Milei, la eugenesia no es política de Estado (al menos no explícitamente), pero funciona como estética de gobierno: una pedagogía del desprecio y de la purificación afectiva.

Tweet

La imagen del niño blanco que circula en el video de @RaceAwakening no es un accidente viral ni una excentricidad reaccionaria. Es el ícono perfecto para un momento donde la argentinidad se redefine como nostalgia racial, como utopía sin mezcla, como ilusión de inocencia anterior a la historia. Ese niño no es el futuro: es la restauración simbólica de un pasado que nunca existió. Una infancia blanca que borra el barro, el mestizaje, la villa, la madre soltera, el cuerpo travesti, el indígena que sobrevive en los márgenes, el negro que no calza en la postal.

El mileísmo no necesita justificar esta operación: la convierte en sentido común. Como en Aporia, como en el algoritmo de selección embrionaria, el blanqueamiento argentino ya no se proclama: se estetiza. Se aplica en forma de recorte presupuestario, de anulación cultural, de desprecio a la ESI, de cancelación de libros, de sarcasmo performático, de odio de clase convertido en eficiencia administrativa.

En este nuevo régimen, lo diverso ya no es combatido abiertamente: es ridiculizado, despreciado, desalojado del centro del relato. La política no es la confrontación entre modelos, sino la producción de un único plano de visibilidad donde solo ciertos cuerpos, ciertas voces, ciertas infancias pueden entrar. Y quienes no encajan deben callar. O desaparecer.

Yuyito González, con su frase coreográfica —“me horrorizo por las cosas que vi”— no necesita enumerar lo visto. Porque la ultraderecha no gobierna con argumentos: gobierna con imágenes y silencios. Muestra una niña con un dedo erecto en la boca y te deja completar la escena. Muestra un niño blanco sin historia y te invita a desearlo como símbolo. Te ofrece afectos listos para usar: horror, ternura, asco, nostalgia. Y convierte el Estado en una sala de edición: se corta, se borra, se colorea.

Frente a eso, el desafío no es solo resistir políticamente. Es volver a narrar. No en el sentido programático, sino en el sentido profundamente ético de construir relatos que no necesiten borrar a nadie para existir. Relatos que no estén hechos de íconos puros sino de mezclas sucias, contradicciones vivas, impurezas históricas. Porque, como escribió Leopoldo Brizuela, “para contar la historia… es preciso ser víctima. Del presente. O de su memoria”. Y porque, como entendió Schwarzböck, lo que no puede decirse vuelve como espanto, como estética vacía, como pantalla negra.

Contar no es recordar. Es interrumpir la imagen. Devolverle historia al ícono. Devolverle cuerpo al símbolo. Devolverle deseo al niño blanqueado por el algoritmo de la restauración. La eugenesia, como el fascismo, no se combate solo con denuncias. Se combate con relato. Con memoria sucia, con archivo vivo, con ficción peligrosa. Con esa forma de literatura que no quiere redimir, sino recordar que lo más humano es justamente lo que no puede ser corregido.

Yesterday, on X, I saw two images that—though seemingly unrelated—condense the paranoid core of the current Argentine regime.

The first was a video posted by the account @RaceAwakening featuring a white child—blond, blue-eyed, porcelain-skinned—offered as an emblem of argentinidad. This wasn’t merely a nostalgic montage but a political affirmation: that child does not represent just any childhood, but an ideal form of citizenship—the estanciero’s heir, purchased with Nazi gold. In that image, the «true» Argentine is white, infantilized, angelic, untainted by mixture or history. A child—not a subject.

In X the account @RaceAwakening featured yesterday a white child—blond, blue-eyed, porcelain-skinned—offered as an emblem of argentinidad. This wasn’t merely a nostalgic montage but a political affirmation of a social order purchased with Nazi gold.

Tweet

The second image circulated as part of an alleged campaign against pedophilia, promoted by journalist Esteban Trebucq, an unofficial mouthpiece for Javier Milei’s government. It shows a girl making a “shh” gesture while a male finger—veiny, adult, erect—rests on her mouth. Worse still, the finger has a phallic tip. The message, in capital letters: “PEDOPHILIA IS A CRIME, NOT A SEXUAL ORIENTATION.” No sane person could oppose that statement. Pedophilia is a crime. Period. But what’s truly disturbing is the visual language used to represent it: not one of direct denunciation, but of sexual ambiguity, where the finger that demands silence embodies the very power it claims to condemn.

The Alt-Right has their mercenaries in the media like journalist Esteban Trebucq. Yesterday he posted an image showing a girl making a “shh” gesture while a male finger with a phallic tip.

Tweet

What these two images share is not their content, but their function: to project onto child bodies the restorative fantasy of a broken masculinity. In a country where the father no longer represents, where the law has become a meme, where the State has been emptied of all symbolic authority, the far right finds in the child’s body—be it whitened or silenced (the girl is not blond, obviously)—a point of anchorage for rebuilding an impossible order.

What these two criminalising images share is not only their purpose and content, but their function: to project onto child bodies the restorative fantasy of a broken masculinity.

Tweet

That white child is not a real being: he’s an avatar of racial purity, a eugenic promise, a nostalgic vision of a nation without mixture. And that girl with the erect finger in her mouth is not a protected victim: she’s a sacrificial spectacle, a support for the moralistic sadism of a patriarchy that no longer dares to name its own desire.

Yuyito González, Milei-aligned evangelical figure, recently said she was “horrified by the things she saw,” without specifying what exactly she saw. She doesn’t have to. What remains unsaid serves its purpose better: everyone projects their own horror. That is the affective pedagogy of fascism—show just enough to incite punishment, omit just enough to enable fantasy.

This is not media scandal. This is ideology. A visual politics of fear driven by a perverse desire. An aesthetics of virile restitution. An affective regime that finds in the white boy and the silenced girl the perfect political bodies to cover over its misogyny, its racism, its extermination drive.

The Horrifying Argentine History

All of this—the purified boy, the silenced girl—does not occur in a vacuum. It happens against a very specific backdrop: a national history that has never been fully told. A history that, instead of being narrated, was displaced into spectacle, myth, or denial. A history that, as Silvia Schwarzböck wrote, became “a black screen.” In Los espantos, she defines the post-dictatorship as a regime of visibility without discourse: “What cannot be said about the dictatorship is what can be seen.” The phrase is brutal. In Argentina, horror is not denied—it is aestheticized, encapsulated, rendered as harmless image. In this, Schwarzböck and my Against the Grain History of Argentine Art (Sudamericana, 2021) are in full agreement. The torturer ceases to be a historical subject and becomes a character: a sadomasochistic villain, nearly fictional. Just like the Nazis in Hollywood. The machinery of extermination becomes set design.

Silvia Schwarzböck said in her wonderful Los espantos that Argentine post-dictatorship was a regime of visibility without discourse where horror is not denied—it is aestheticized.

Tweet

That “black screen” Schwarzböck refers to—mute, opaque, unrepresentable—is what remains when storytelling fails. When language falls short. When memory turns into an empty form. That’s why the image of the white boy from @RaceAwakening functions as a substitute: it is an image against horror, an attempt to restore innocence where there was terror. A child without history is the best antidote to the archive.

The late and wonderful Argentine writer Leopoldo Brizuela sensed this in his award-winning novel Una misma noche (Alfaguara), when he wrote: “Perhaps only literature could forgive. Literature, that future reader.” But that reader never arrives. Or if they do, they don’t want to know. In the novel—a reckoning with the narrator’s own cowardice during the dictatorship—he admits that it is not enough to have seen: one must be able to tell. And in Argentina, telling is always an interrupted act, hesitant, marked by the fear of saying too much or too little.

The late Argentine writer Leopoldo Brizuela sensed this in his award-winning novel Una misma noche (Alfaguara), when he wrote: “Perhaps only literature could forgive. Literature, that future reader.” But that reader never arrives. He and she will arrive. I believe is already haunting us.

Tweet

At a key moment, Brizuela writes: “To tell the story… one must be a victim. Of the present. Or of its memory.” And that is where the present regains meaning: in the way new forms of fascism reactivate past traumas without naming them, without explaining, without assuming them. The white boy and the silenced girl are precisely the figures that emerge when one can no longer—or no longer wishes to—speak the truly intolerable: the pact of whiteness that founded the nation, the indigenous genocide, the structural sexual violence, the complicity of the middle classes with terror.

If post-dictatorship art sought to represent horror without speaking directly of horror—a choreography of elliptical gestures, metaphors, abstractions—what we are witnessing today is its brutal reverse: hyperrepresentation that erases, denunciation that eroticizes, innocence that conceals. Mileist Argentina does not deny the past—it replaces it with a redemptive, infantilized, mute whiteness. And like all reactionary narratives, this one has its aesthetic: washed-out tones, frozen smiles, clean gazes, bold fonts. Order needs no argument when it has an image.

Mileist Argentina does not deny the past—it replaces it with a redemptive, infantilized, mute whiteness.

Tweet

The Queer Aristocrat and National Eugenics

The white child now circulating as a symbol of argentinidad is not new. He is a reincarnation. His lineage traces back to the enlightened elites of the late 19th century, when Argentina’s ruling classes—while building libraries and railways—were also designing a racially purified future for the country. That was when the equation between progress and whiteness, civilization and desire control, republic and eugenics took hold.

A key figure from that period is Carlos Octavio Bunge: sociologist, jurist, educator, and—as Joseph M. Pierce shows in Argentine Intimacies—a queer aristocrat. Bunge belonged to the elite Bunge family and was one of the ideological architects of Argentine positivist nationalism. He dressed like a dandy, wrote with decadentist flair, and moved in circles where male sensitivity deviated from hegemonic virility. But the gender ambiguity that Pierce romanticizes didn’t marginalize him. On the contrary—it reinforced his authority as an aesthetic curator of a white, orderly, masculine nation.

Pierce recognizes that tension with apparent lucidity, prompting the question: why is a queer Indigenous scholar so invested in this figure? “Carlos Octavio Bunge, a fin-de-siècle dandy, was also the author of projects that justified the ethnic cleansing of Indigenous peoples in the name of progress.” In his book Nuestra América (1926), Bunge offers a racialized view of the continent, arguing that Argentina should preserve itself through “desirable” immigration—European, white, disciplined—and the exclusion of “degenerates,” a concept directly inherited from European eugenic rhetoric.

What is disturbing—and fascinating—about Bunge is that he embodies the structural complicity between sexual dissidence and ideological whitening. He was not an outsider; his queer sensitivity enabled him to serve as the aesthetic engineer of the national body: whiter, more orderly, more rational. Bunge was no victim of the system—he was its architect. His legacy—merging pedagogy, scientific racism, and elite eroticism—still pulses in today’s technocratic, hygienic, meritocratic authoritarianisms.

Pierce romanticizes deviance. But not all strangeness is dissidence, and not all dissidence resists power. Sometimes, deviation serves to renovate the norm, to redesign it, to make it even more efficient. The queer aristocrat doesn’t break the social pact—he embellishes it. Makes it desirable. The genealogy of our national eugenics is not purely medical or police-driven. It is also aesthetic. Also affective. Also sexual. The nation that dreamed itself white was shaped by desire. And that desire was not always heterosexual—but it was deeply normative: it sought to control mixture, rank bodies, and convert education and science into tools of social filtration.

The white boy from @RaceAwakening is a direct descendant of that utopia. He doesn’t rise from the people, from the mud. He comes from the archive, from the racial curation woven by enlightened elites. Like his ancestor Bunge, this boy has no desire: his function is to represent an ideal form of humanity without mixture, without conflict, without stain. He is the perfect icon of purifying nationalism: ahistorical, untroubled, immaculate.

The Queer Aristocrat and National Eugenics

The white child now circulating as an emblem of argentinidad is not new. He is a reincarnation. His lineage traces back to the enlightened elites of the late 19th century, when Argentina’s ruling classes—while founding libraries and railways—were also designing a racially purified future for the nation. It was then that the equation between progress and whiteness, civilization and desire-control, republic and eugenics was consolidated. A key figure from this period is Carlos Octavio Bunge—sociologist, jurist, educator, and, as Joseph M. Pierce shows in Argentine Intimacies, a queer aristocrat. A member of the elite Bunge family, he was one of the ideological architects of Argentine positivist nationalism. He dressed like a dandy, wrote with decadentist passion, and moved in circles where male sensibility diverged from hegemonic virility. But that gender ambiguity, which Pierce romanticizes, did not remove him from power. On the contrary: it strengthened his position as an aesthetic strategist of a nation imagined as white, ordered, and masculine.

The white child now circulating as an emblem of argentinidad is not new. His lineage traces back to the enlightened elites of the late 19th century, when Argentina’s ruling classes designed a racially purified future,

Tweet

Pierce recovers that tension, raising the question of why a queer Indigenous academic like him devotes such attention to him. “Carlos Octavio Bunge, a fin-de-siècle dandy, was also the author of projects that justified the ethnic cleansing of Indigenous peoples in the name of progress.” In Nuestra América (1926), Bunge offered a racialized vision of the continent, arguing Argentina must preserve itself through the incorporation of “desirable” immigrants—white, European, disciplined—and the exclusion of “degenerates,” a concept lifted directly from European eugenic rhetoric.

What is disturbing—and fascinating—about Bunge is that he embodies the structural complicity between sexual dissidence and ideological whitening. He was not an outsider; his queer sensitivity helped him function as the aesthetic curator of a new national body: whiter, more ordered, more rational. Bunge was not a victim of the system—he was its architect. His legacy—blending pedagogy, scientific racism, and elite eroticism—still reverberates in today’s forms of technocratic, hygienic, meritocratic authoritarianism.

Pierce romanticizes deviation. But not all strangeness is dissidence, and not all dissidence resists power. Sometimes deviation serves to renew the norm, to redesign it, to make it even more effective. The queer aristocrat does not break the social pact—he beautifies it. Makes it desirable. The genealogy of Argentine eugenics is not merely medical or carceral—it is also aesthetic, affective, and sexual. The nation that imagined itself white was built on desire. And that desire was not always heterosexual, but it was deeply normative: it sought to control mestizaje, rank bodies, and above all, turn education and science into tools of social filtration.

The white child of @RaceAwakening is a direct descendant of that utopia. He is not born of the people or the soil. He is born from the archive, from the racial curation spun over decades by enlightened elites. Like his ancestor Bunge, this child has no desire: his role is to represent an ideal of humanity that excludes mixture, conflict, or eroticism. He is the perfect icon of purifying nationalism: ahistorical, untroubled, unblemished.

Cadets, Purification, and the Pedagogy of Pain

If the white child is the final image of the ideal citizen, the Argentine cadet is its brutal transitional phase. He is not yet that polished body, but he is no longer the mestizo, popular, unruly body. He is a body in formation: corrected, exposed to pain, redirected toward obedience. In Argentina, the figure of the cadet—military, police, or penitentiary—functions as a machine of social purification. Every so often, the system claims lives. And no one seems to care much.

If the white child is the final image of the ideal citizen, the Argentine cadet is its brutal transitional phase. No longer the mestizo, popular, unruly body. He is a body in formation: corrected, exposed to pain, redirected toward obedience.

Tweet

The cases piled up: cadets dead from dehydration, asphyxiated from overexertion, victims of collective beatings in training sessions masked as “character building.” Official discourse spoke of accidents, of “individual excesses,” of isolated failures. But what these episodes actually revealed was a systematic regime of constructing the national male body: white, strong, heteronormative, desire-resistant, and useful for punishment.

Today, the pedagogy of pain still structures these institutions. It is a modernized form of eugenics. It is no longer about measuring skulls or applying racial theories, but about forging bodies through physical suffering as a filter of moral aptitude. Those who endure, survive. Those who don’t, are surplus. The ideal is not the critical citizen, not even the thinking soldier: it is the body that obeys and punishes. The body that remains silent.

But like all eugenic devices, the cadet school was also saturated with sexual ambivalence. Confinement, nudity, constant surveillance of other bodies, choreographed routines of discipline and humiliation—all produce an unspoken erotic field. The queer was not absent. It was central to the dispositif. But far from being celebrated, it was harnessed for control.

This ambiguity is not innocent. The formation of the Argentine cadet was always designed to repress desire while also drawing from it. What is punished in public is consumed in private. What is denied in discourse appears as ritual scene. Every body marked by pain, every scream in training, every normalized death has served to symbolically restore the lost authority of the father, the State, the patria. The blows carried an erotic charge that drove them.

In this context, masculinity is not biological—it is a political technology. A masculinity that is not inherited but imposed, tested, suffered. That’s why every death in the cadet schools over the decades was not a mistake—it was the price of sustaining the fiction of a nation ordered by strong, white, obedient men. Just as the white child from @RaceAwakening is a desireless icon, the cadet dead in training becomes a historyless martyr. Neither speaks. Neither remembers. Neither soils the purity of the narrative.

Aporia and the Eugenic Renaissance: Purity as Startup

In one of the key encounters during his infiltration for UK’s The Guardian newspaper, journalist “Chris” gains access to an even more exclusive circle: that of the new engineers of white supremacy. There he meets Matthew Frost, a former British professor who, under the pseudonym “Matt Archer,” runs Aporia, an online journal dedicated to the study and dissemination of so-called HBD—“human biodiversity”—a polished euphemism for what it has always been: the attempt to hierarchize life based on genetic traits.

What stands out about Aporia is not its content—old theories dressed in new clothes—but its form. It’s a sleek platform with minimalist design, muted blue tones, and academic jargon. Instead of racist pamphlets, it publishes articles on “predicting intelligence in embryos,” “population differences in behavior,” and “the demographic collapse of European civilization.” No swastikas, no shouting—just data, charts, algorithms.

Frost confides to Chris that the project is backed by an anonymous American tech investor. He also reveals a partnership with Danish researcher Emil Kirkegaard, a central figure in the new digital eugenics network. Kirkegaard runs what is now called the Human Diversity Foundation, a business entity registered in a U.S. state with lax laws, directly descended from the infamous Pioneer Fund, which financed Nazi propaganda films like Erbkrank in the 1930s.

“This is like the Pioneer Fund, but upgraded. More efficient, more discreet. A think tank that runs like a startup. Ten guys, a million pounds, an algorithm, and a mission.” The mission? To promote what he calls “the new cognitive elite”

Tweet

But the most revealing moment comes at a private dinner. There, Frost drops the metaphor: “This is like the Pioneer Fund, but upgraded. More efficient, more discreet. A think tank that runs like a startup. Ten guys, a million pounds, an algorithm, and a mission.” The mission? To promote what he calls “the new cognitive elite”: selecting embryos with high IQs, encouraging reproduction among people with “favorable genes,” discouraging birth in “dysfunctional” populations, and eventually legislating the “remigration” of racialized groups back to their countries of origin. All in the name of order, efficiency, the future.

This is no longer classic Nazism. This is eugenics 2.0, powered by Excel spreadsheets and TED Talk aesthetics. No need to rally crowds or reeducate populations—just create tools that normalize genetic optimization as a private, desirable, even loving decision. In other words: “We don’t choose the smartest because we hate the others, but because we want the best for our children.” In this new regime, the white child is no longer just the icon of a pure nation. He becomes a genetic investment, an affective and symbolic capital projecting the future of an elite that believes itself destined to outlive global catastrophe. He is not a body, but a future vector. A perfect child.

This is no longer classic Nazism. This is eugenics 2.0, powered by Excel spreadsheets and TED Talk aesthetics.

Tweet

And the discourse that was once exclusionary becomes enveloping. Supremacy is no longer shouted—it is programmed. No longer a command, but a suggestion. It is not imposed by the state, but emerges from consumer preference. That is how neoliberal eugenics works: under the mask of freedom, it offers a world where some bodies are selected—and others simply never come into existence.

This is the new face of fascism: not the soldier, but the engineer. Not the pastor, but the investor. Not the criminal, but the loving father who “just wants what’s best.”

Nikolas Rose and the Gentle Face of Eugenics

If in the twentieth century eugenics was imposed from above—through laws, confinement, and public campaigns of racial hygiene—in the twenty-first century it returns from below. Or from within. From freedom. From affection. From the “informed decisions” of responsible individuals. Governance over life no longer prohibits, but optimizes. It no longer dictates who may live, but helps people “choose better.”

This is biocitizenship: a new form of subjectivity that manages its body as a project, its reproduction as a strategic plan, and its health as an investment. He warns that under this paradigm, eugenics doesn’t disappear—it becomes a market option. A right. An affective duty. We see it in mental health discourses urging us to “take care of ourselves,” to “be the best version of ourselves,” while simultaneously placing the full burden of suffering on the individual. We see it in ecological narratives that blame overpopulation for the planet’s collapse and promote demographic degrowth to “save the Earth.” We see it in AI platforms selecting embryos based on likely academic success. And we see it, too, in the industry of genetic celebrity.

Today, celebrities and entrepreneurs engage in aspirational eugenics. It’s not about exclusion, but about producing desirable heirs. The elite is no longer defined by surname, but by DNA. The fascination with the “perfect children” of influencers, athletes, actresses, and scientists configures a new aesthetic of purity. The difference is that now it is not imposed by state decree but by cultural aspiration. And that makes it harder to contest.

In that regime, the white child ceases to be merely a national symbol. He becomes an emotional consumer product, a curatorial act of lineage. The desire to have a healthy, intelligent, normative, functional, kind child becomes an intimate, unquestionable mandate. And with it, the eugenic matrix is reactivated—without saying it: disability is discarded, difference is discarded, the unpredictable is discarded.

The problem, says Rose, is not the technology. It is the story. The narrative we construct to justify why we choose some bodies over others. And what that story reveals is that behind the discourse of well-being lies an ancient impulse: to order the world, to cleanse the margins, to eliminate what does not adapt. That is why the new eugenics needs no concentration camps. An app, a bank account, and a compelling emotional narrative suffice. What was once done by decree is now done by love.

Argentina: Late Laboratory of a Future That Already Happened

This entire biopolitical, emotional, technocratic architecture —the architecture of voluntary enhancement, curated desire, the perfect child—is already underway in Argentina, though with the melancholic delay of a culture that always arrives late to its own modernization. In Milei’s aesthetic regime, eugenics is not official state policy (at least not explicitly), but it functions as a governing aesthetic: a pedagogy of contempt and affective purification.

The image of the white child in the @RaceAwakening video is no viral accident or reactionary eccentricity. It is the perfect icon for a moment when argentinidad is redefined as racial nostalgia, as unmixed utopia, as a fantasy of innocence prior to history. That child is not the future: he is the symbolic restoration of a past that never existed. A white childhood that erases the mud, the mestizaje, the villa, the single mother, the travesti body, the Indigenous survivor in the margins, the Black child who doesn’t fit the postcard.

Mileism does not need to justify this operation—it installs it as common sense. As in Aporia, as in the embryo selection algorithm, Argentine whitening is no longer proclaimed: it is aestheticized. It arrives as a budget cut, a cultural erasure, a disdain for sex education, a cancellation of books, a performance of sarcasm, a conversion of class hatred into administrative efficiency.

In this new regime, diversity is no longer openly fought—it is ridiculed, scorned, evicted from the center of the narrative. Politics is not the clash of models, but the production of a single plane of visibility where only certain bodies, voices, and childhoods can appear. Those who don’t fit must stay silent—or disappear.

Yuyito González, with her choreographed phrase—“I was horrified by what I saw”—does not need to specify what she saw. Because the far right does not govern with arguments: it governs with images and silences. It shows a girl with an erect finger in her mouth and lets you complete the scene. It shows a white child without history and invites you to desire him as a symbol. It offers ready-made emotions: horror, tenderness, disgust, nostalgia. And it turns the state into an editing room: it cuts, erases, color-corrects.

In the face of that, the challenge is not just to resist politically. It is to narrate again. Not in a programmatic sense, but in the profoundly ethical sense of crafting stories that do not need to erase anyone to exist. Stories not made of pure icons, but of messy mixtures, living contradictions, historical impurities. Because, as Leopoldo Brizuela wrote, “to tell the story… one must be a victim. Of the present. Or of its memory.” And because, as Schwarzböck understood, what cannot be said returns as horror, as empty aesthetics, as black screen.

To tell is not to remember. It is to interrupt the image. To return history to the icon. To return a body to the symbol. To return desire to the child whitened by the algorithm of restoration. Eugenics, like fascism, cannot be fought with denunciations alone. It must be fought with story. With dirty memory, with live archive, with dangerous fiction. With that kind of literature that does not seek redemption, but reminds us that the most human thing is precisely what cannot be corrected.

Deja una respuesta