SCROLL DOWN FOR THE ENGLISH VERSION

Sobre amistad, fungibilidad y cuerpos que sobran

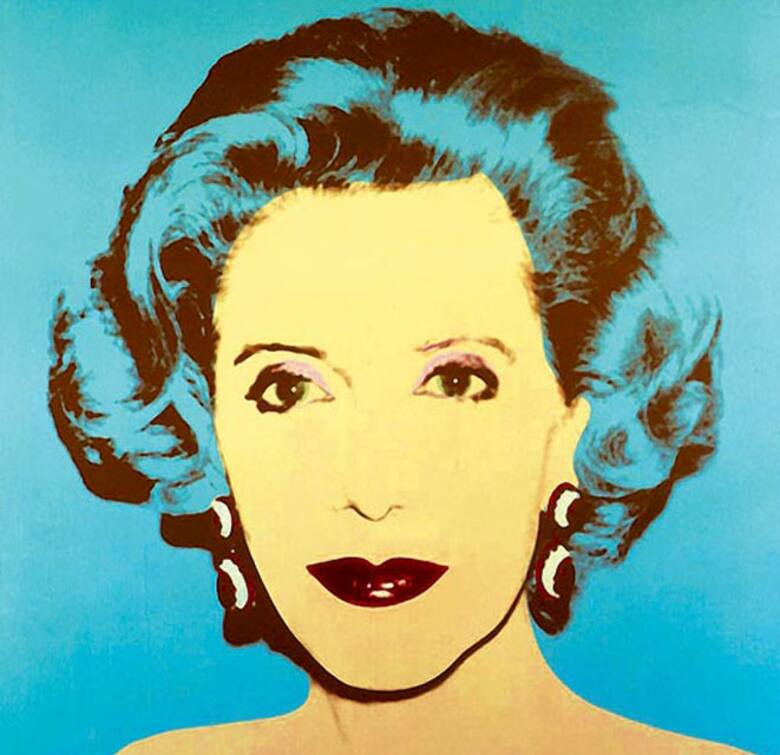

En los últimos días, Ama Amoedo volvió a ocupar su lugar habitual: el de escenografía viva del capital simbólico latinoamericano. Esta vez fue cantando —sí, cantando— en la Casa del Arte, como si la aristocracia del mecenazgo hubiera descubierto en el karaoke la forma más honesta de decir “no tengo nada para decir”. El gesto kitsch, lejos de ser paródico o liberador, revela el grado cero del afecto: no hay ironía, hay coreografía. No hay subjetividad, hay inversión. Lo que canta no es ella: es el capital.

“La mafia del amor es una coreografía de validaciones mutuas. El ‘te quiero’ no es afecto: es contraseña para entrar a un sistema de favores.”

Tweet

Pero esto no es nuevo. Viene después de la fiesta que ofreció para Mirtha Legrand, una suerte de aquelarre de unicornios y Ozempic en la que el glamour funcionó como dispositivo de limpieza de clase: los cuerpos estaban todos intervenidos, las caras todas sabidas, las sonrisas todas necesarias. Nadie estaba ahí porque quisiera: estaban porque no estar era no existir.

Lo que asombra no es el gesto, sino la matriz de sentido que lo produce. Porque Amoedo no vive rodeada de amigxs, sino de elementos de un ecosistema afectivo cuya regla de oro es la fungibilidad. En ese mundo, la amistad no es un lazo: es una cláusula. Un contrato implícito que exige disponibilidad, adhesión, silencio. Y, sobre todo, reciprocidad ficticia. En esa lógica, ser amigx de Amoedo no es conocerla, quererla o compartir algo. Es haber sido validado por el algoritmo social de la oligarquía cultural. Haber sido útil.

“En el mundo Amoedo, la amistad no es un lazo sino una cláusula. No importa quién sos, sino si podés ser usado.”

Tweet

Y acá la palabra clave es utilidad. En los círculos donde circula Amoedo, la amistad no tiene contenido afectivo: tiene función estratégica. No se trata de compartir una historia sino de ocupar una posición. La gente no se elige, se selecciona. Y cuando una posición deja de ser funcional, se la reemplaza. Así, la amistad se vuelve intercambiable: lo que importa no es quién sos sino que ocupes el lugar que se espera de vos.

Esto es lo que llamo la mafia del amor: una forma de comunidad basada no en el afecto, sino en su simulacro. No en el vínculo, sino en la gestión del vínculo. Un régimen de cercanía administrada que disfraza de “familia” lo que en realidad es una coreografía de validaciones mutuas. Donde el “te quiero” es una contraseña para acceder a un sistema de favores.

Y donde cualquier afecto que no pueda ser anticipado, estetizado o devuelto —un gesto no funcional, no calculado, no convertible en capital relacional— debe ser rápidamente ridiculizado o absorbido como rareza. Porque ese tipo de afecto, impredecible y no rentable, amenaza con desarmar la coreografía. Expone que todo esto —la familia del arte, la comunidad simbólica, la amistad curada— no es una forma de estar con otros, sino un modo de preservar una escenografía de pertenencia. Un decorado.

“Cualquier afecto que no pueda ser devuelto o estetizado es ridiculizado. Porque amenaza con desarmar la coreografía.”

Tweet

Ozempic, gordura y biopolítica: cuerpos que (no) pertenecen

El contraste entre la artista gorda y la mecenas con Ozempic no es anecdótico. Es la expresión corporal de un régimen de pertenencia estética y política. Mientras el cuerpo gordo incomoda, ralentiza y escapa a la economía de la optimización, el cuerpo intervenido de la mecenas se vuelve vehículo de gobernabilidad afectiva. Es un cuerpo funcionalizado: flaco, hormonado, medicalizado, vigilado.

“El Ozempic no es solo una droga: es un régimen de legitimación. El cuerpo intervenido circula; el cuerpo gordo incomoda.”

Tweet

Como plantea Paul B. Preciado, en el capitalismo farmacopornográfico, el cuerpo deja de ser un dato biológico para convertirse en una tecnología de administración subjetiva. La delgadez no es un estado, es un régimen; el Ozempic, su dispositivo. No es solo una droga: es una forma de gobierno estético que regula quién puede circular, quién puede hablar, quién puede pertenecer.

El cuerpo gordo, por el contrario, no puede mentir. No puede ser neutralizado por completo ni estetizado sin riesgo. En el arte latinoamericano post-Rojas, la gordura sigue funcionando como el síntoma que el mecenazgo quiere borrar: del VIH, del hambre, del desborde sexual, de la improductividad. La artista gorda no cabe en la coreografía Amoedo porque su cuerpo no puede ser narrado como éxito. Solo como resto.

Y si el Centro Cultural Rojas fue, en su momento, el laboratorio donde se ensayó la estetización del dolor queer —como escribí en mi tesis—, hoy Paola Vega y Ama Amoedo actualizan esa operación en clave nostálgica y patrimonial. Convierten la peste en patrimonio. La disidencia en colección. El dolor en relato autocuratorial. Todo bajo la condición de que los cuerpos que lo encarnaron ya no estén, o estén debidamente delgados, controlados, estetizados.

En la Colección Fortabat, Paola Vega y Amoedo convirtieron la peste en relato patrimonial, dematerializandolo. Lo único que importa en ese museo es la gordura como fantasma o como lípido.

Tweet

La falsa igualdad de la amistad entre ricos

Frente a esto, es tentador volver a las distinciones clásicas sobre la amistad. En el griego antiguo, philia no era una emoción ni un sentimiento vago, sino una relación ética fundada en la reciprocidad, el reconocimiento mutuo y el bien compartido. Se la oponía a eros (deseo) y a agape (amor divino), y se distinguía de philoxenia, la hospitalidad hacia el extranjero. En su centro estaba la virtud, la comunidad, la figura del philos como aquel con quien se comparte un mundo.

Pero esta idealización merece ser desmontada. Porque para que existiera philia en la polis griega, tenía que existir también la desigualdad estructural. La comunidad de amigxs libres y virtuosos se sostenía sobre una economía de cuerpos esclavizados, mujeres sin ciudadanía y extranjerxs sin derecho. La amistad, en ese mundo, no era universal: era el lujo de los iguales, es decir, de los ricos. La philia clásica no era una apertura, sino una frontera: una tecnología de inclusión que operaba por exclusión. No podías ser philos si no estabas ya dentro.

“En Grecia, para que haya philia, tiene que haber esclavos. La amistad era el lujo de los que ya estaban adentro.”

Tweet

Eso es exactamente lo que el circuito Amoedo reproduce: una fantasía de philia sin condiciones materiales. Una comunidad de supuesta igualdad donde solo acceden los seleccionados. Un régimen de afecto que se imagina horizontal, pero que está sostenido por la precarización, la invisibilización y el silenciamiento de todo lo que no encaja. Bajo el barniz de la intimidad simbólica y la “familia del arte”, lo que hay es una curaduría afectiva: una distribución calculada de la cercanía que se presenta como amor, pero opera como exclusión codificada.

Philoxenia queer: hospitalidad sin comunidad

Por eso, quizás lo que habría que reivindicar no es la philia, sino la philoxenia: la apertura hospitalaria a aquel que no forma parte, al extraño, al impropio. No la comunidad cerrada de los amigos funcionales, sino el riesgo de una relación sin garantías. Y aquí podemos pensar con Tim Dean, que recupera la figura del sexo anónimo como una forma de encuentro no codificado por las narrativas de pertenencia, pureza o simetría. Un contacto que no busca construir comunidad, sino que interrumpe la lógica del intercambio. Que no quiere ser devuelto, ni reconocido, ni convertido en identidad.

“Frente a la amistad curada como exclusión, solo queda la elegante philoxenia: el gesto que no se devuelve y desarma al anfitrión.”

Tweet

La philoxenia queer, en ese sentido, no es una ética de la afinidad, sino del desvío. No se funda en la estabilidad de los roles, sino en el temblor del encuentro. Frente a la fungibilidad de la mafia del amor, y frente a la falsa simetría de la philia oligárquica, solo queda abrirse a lo que no puede ser capitalizado: el gesto incondicional que desarma al anfitrión, que lo hace vulnerable, que lo pone en peligro. Porque a veces, solo en ese desborde, hay posibilidad real de algo parecido a una amistad.

On friendship, fungibility and bodies that don’t belong in the art system

In recent days, Ama Amoedo, heiress to the cement empire consolidated by Amalia Lacroze de Fortabat returned to her usual role: that of a living stage prop for Latin American symbolic capital. This time it was by singing—yes, singing—at the Casa del Arte, as if the aristocracy of art patronage had discovered in karaoke the most honest way of saying “I have nothing to say.” The kitsch gesture, far from ironic or liberating, revealed affection at zero degrees: there was no irony, just choreography. No subjectivity, just investment. It wasn’t she who sang: it was capital.

The “love mafia” isn’t about affection. It’s about managing proximity, simulating intimacy, and enforcing silence through favours.

Tweet

But none of this is new. It comes after the party she hosted for Mirtha Legrand, a sort of unicorn-and-Ozempic coven where glamour operated as a class-cleansing device: every body intervened, every face already known, every smile utterly necessary. Nobody was there out of desire: they were there because not being there meant not existing.

What is striking is not the gesture, but the logic that produces it. Because Amoedo is not surrounded by friends, but by elements of an affective ecosystem whose golden rule is fungibility. In that world, friendship is not a bond; it’s a clause. An implicit contract demanding availability, adhesion, silence—and above all, fictional reciprocity. In this logic, being Amoedo’s friend doesn’t mean knowing her, loving her, or sharing anything. It means having been validated by the social algorithm of cultural oligarchy. It means being useful.

In Amoedo’s world, friendship is not a bond—it’s a clause. Who you are matters less than what position you occupy.

Tweet

And here the keyword is utility. In the spaces where Amoedo circulates, friendship has no affective content: it has strategic function. People aren’t chosen, they’re selected. And when a position ceases to be functional, it’s replaced. Friendship becomes interchangeable: who you are doesn’t matter, only whether you fulfill the role expected of you.

This is what I call the love mafia: a form of community based not on affection, but on its simulation. Not on bonds, but on the management of bonds. A regime of managed closeness that dresses itself up as “family” but in reality performs a choreography of mutual validation. Where “I love you” is not an emotion, but a password to access a system of favors.

Ozempic is not just a drug. It’s a biopolitical device that governs who gets to belong—and whose body must disappear.

Tweet

And where any gesture of affection that cannot be anticipated, aestheticized or reciprocated—any uncalculated, non-functional act that cannot be converted into relational capital—must be quickly ridiculed or absorbed as anomaly. Because such unpredictable, unprofitable affection threatens to unravel the choreography. It exposes what all this is: not a way of being with others, but a means of preserving a scenography of belonging. A decor.

Ozempic, Fatness and Biopolitics: Bodies That (Don’t) Belong

The contrast between the fat artist and the patron slimmed down on Ozempic is not anecdotal. It is the bodily expression of a regime of aesthetic and political belonging. While the fat body discomforts, slows down, and escapes the logic of optimization, the intervened body of the patron becomes a vehicle of affective governability. It is a functionalized body: slim, hormonally regulated, medicalized, surveilled.

Post-Rojas patronage turns queer pain into heritage and HIV into decor—as long as the bodies are gone or aestheticized.

Tweet

As Paul B. Preciado has argued, in the pharmacopornographic capitalism we inhabit, the body is no longer a biological given but a technology of subjective administration. Thinness is not a state, it is a regime; Ozempic, its device. It’s not merely a drug: it’s a form of aesthetic government that regulates who can circulate, who can speak, who is allowed to belong.

Ancient philia wasn’t universal. It was the luxury of rich men in a society built on slaves, women without rights, and silenced foreigner

Tweet

The fat body, on the other hand, cannot lie. It cannot be fully neutralized or aestheticized without risk. In post-Rojas Latin American art, fatness still operates as the symptom that patronage wants to erase: of HIV, of hunger, of sexual excess, of unproductivity. The fat artist does not fit into Amoedo’s choreography because her body cannot be narrated as success. Only as remainder.

And if the Centro Cultural Rojas was once the laboratory for aestheticizing queer pain—as I argued in my thesis—today Paola Vega and Ama Amoedo update that operation in nostalgic and patrimonial terms. They turn plague into heritage. Dissidence into collection. Pain into self-curated narrative. All under one condition: that the bodies who lived it are no longer there, or are sufficiently slim, controlled, aestheticized.

Philoxenia doesn’t seek community—it interrupts it. It begins where recognition, identity, and return are no longer required.

Tweet

The False Equality of Rich People’s Friendship

Faced with all this, it’s tempting to return to classical distinctions on friendship. In Ancient Greek, philia was not a vague emotion or feeling, but an ethical relation rooted in reciprocity, mutual recognition, and shared virtue. It stood in contrast to eros (desire) and agape (divine love), and was distinct from philoxenia, the hospitality extended to strangers. At its center was the idea of virtue, community, the philos as one with whom a world is shared.

But this idealization demands to be dismantled. Because for philia to exist in the Greek polis, structural inequality had to exist too. The community of free, virtuous friends stood atop a social order of enslaved bodies, disenfranchised women, and foreign subjects without rights. Friendship, in that world, was not universal: it was the luxury of equals—that is, of the rich. Classical philia was not openness, but a border: a technology of inclusion that operated through exclusion. You could not be philos unless you were already inside.

And that is precisely what the Amoedo circuit reproduces: a fantasy of philia without material conditions. A supposedly egalitarian community where only the selected few are allowed in. An affective regime that imagines itself as horizontal, but is structurally sustained by precarity, silencing, and the invisibilization of whatever doesn’t fit. Under the gloss of symbolic intimacy and the “art family,” what actually takes place is a curatorial management of proximity: a calculated distribution of closeness that presents itself as love, but operates as codified exclusion.

Philoxenia: Hospitality Without Community

That is why perhaps what needs to be reclaimed is not philia, but philoxenia: the act of welcoming the one who does not belong, the outsider, the improper. Not the closed circle of functional friends, but the risk of a relationship with no guarantees. And here we can think with Tim Dean, who reclaims anonymous sex as a form of encounter not codified by narratives of belonging, purity or symmetry. A contact that does not seek to build community, but to interrupt the logic of exchange. That wants neither return, nor recognition, nor identity.

Queer philoxenia, in this sense, is not an ethics of affinity but of deviation. It is not grounded in stable roles, but in the trembling of the encounter. Against the fungibility of the love mafia, and against the false symmetry of oligarchic philia, what remains is to open oneself to what cannot be capitalized: the unconditional gesture that disarms the host, that renders them vulnerable, that puts them at risk. Because sometimes, only in that overflow, is there any real possibility of something resembling friendship.

buy my book 4th edition

Hacete Socio de mi Canal de Youtube como Miembro Pago

Deja una respuesta