Liturgias de la sangre: Villarruel, Bullrich, Milei y la patria en sacrificio

Este fin de semana, la vicepresidenta Victoria Villarruel viajó a Corrientes para depositar simbólicamente las cenizas del Sargento Cabral, el héroe popular que, según el mito fundante, entregó su vida para salvar a San Martín. El gesto fue más que un acto de homenaje: fue un sacrificio ritual. En paralelo, Villarruel denunció públicamente el hostigamiento de los trolls digitales de Javier Milei y del dueño del medio La Derecha Diario, a quienes acusó de perseguirla por haber apoyado al candidato radical en la provincia. Así se reveló no solo la fractura del oficialismo, sino también la disputa de fondo: quién administra la sangre de la Nación, bajo qué forma y para qué altar.

La vicepresidenta Victoria Villarruel viajó a Corrientes para depositar las cenizas del Sargento Cabral, el héroe popular que, según el mito fundante, entregó su vida para salvar a San Martín. Fue un ritual sacrificial.

Tweet

La Argentina no debate hoy sobre leyes o instituciones, sino sobre cadáveres y liturgias. La sangre ha vuelto al centro del poder: no como metáfora, sino como tecnología. En este nuevo régimen, ya no se discute si debe haber violencia, sino quién la ejerce, para qué Dios y con qué cuerpo. Milei, Bullrich y Villarruel no representan posiciones ideológicas: representan rituales distintos del sacrificio.

La Argentina no debate hoy sobre leyes o instituciones, sino sobre cadáveres y liturgias. La sangre ha vuelto al centro del poder: no como metáfora, sino como tecnología.

Tweet

Javier Milei sacrifica sin altar. Su violencia es silenciosa, eugenésica, automatizada. En su visión, la sangre no se ofrece: se elimina. Su gobierno no produce mártires, sino descartes. No hay tumbas, ni placas, ni duelo: hay datos. Como un virrey digital, ejecuta órdenes del mercado internacional y borra lo que no produce. Su vínculo con la sangre es clínico, obsesivo, casi científico. No cree en el sacrificio como redención, sino en la eliminación como eficiencia. De ahí su fascinación por la clonación, la ingeniería genética, la idea de un cuerpo futuro sin historia ni trauma. En su reino, los jubilados no mueren: dejan de existir.

Milei, Bullrich y Villarruel no representan posiciones ideológicas: representan rituales distintos del sacrificio.

Tweet

Patricia Bullrich, en cambio, cree en la sangre como linaje. Viene de Alvear. De la República oligárquica. De una aristocracia que no necesitó de la fe, porque tenía apellidos. Su sangre no se ofrenda: se presume. No necesita reliquias, porque ya es heredera. Pero esa sangre es estéril. No produce, no fecunda, no ordena. Se limita a castigar. Bullrich encarna un liberalismo sádico y decadente: el de la represión caótica, la policía drogada, la doctrina Chocobar. Su vínculo con el Mossad revela otro tipo de liturgia: una violencia sin redención, sin promesa, sin comunidad. Sólo castigo, sólo control, sólo supervivencia del mando. Como buena heredera, ejecuta sin saber a quién sirve.

Patricia Bullrich, en cambio, cree en la sangre como linaje. Pero esa se limita a castigar. Bullrich encarna un liberalismo sádico, la doctrina Chocobar. Su vínculo con el Mossad revela otro tipo de liturgia: una violencia sin redención, Como buena heredera, ejecuta sin saber a quién sirve.

Tweet

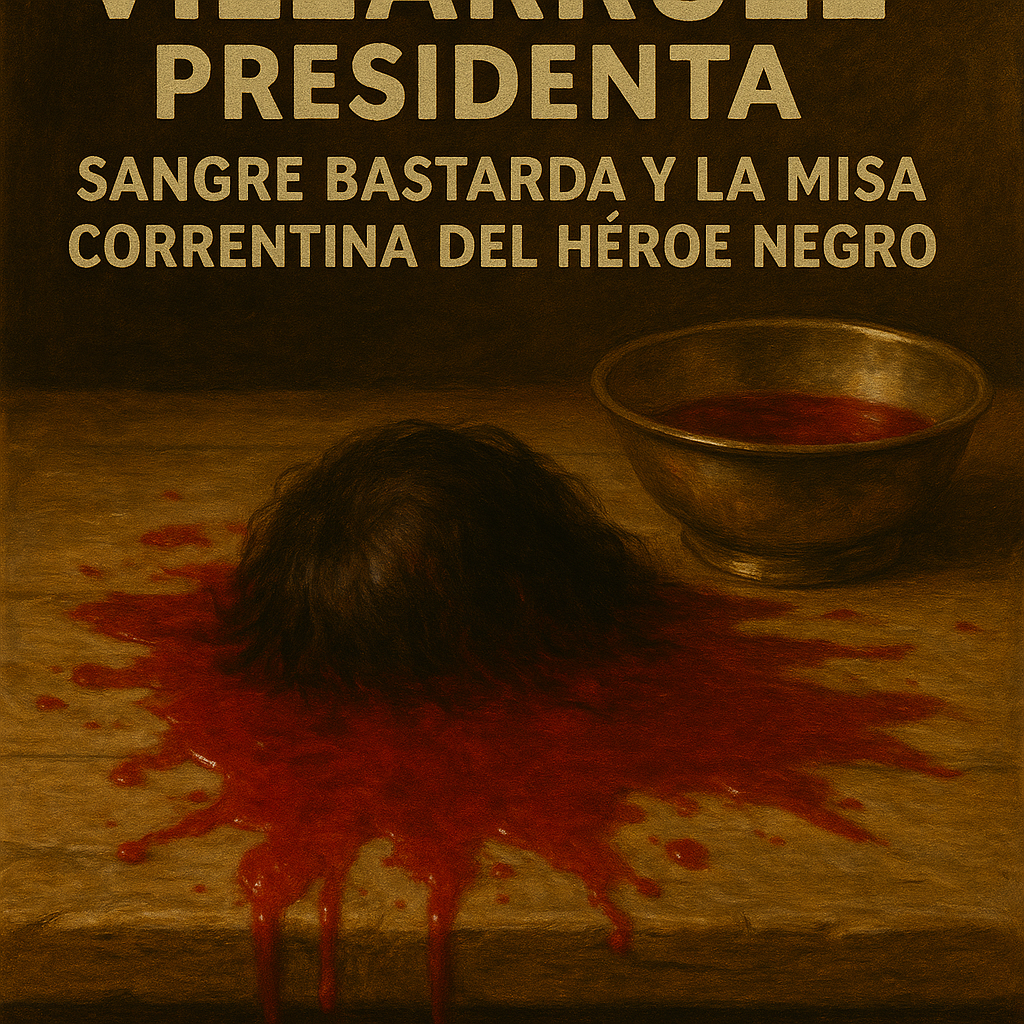

Villarruel entra por otra puerta. Vela. Ella es la sacerdotisa del hueso. Su sangre no es heredada, ni eliminada: es sangre impura que necesita ser consagrada. Lleva en su cuerpo la mancha: mujer, hija de represor, sin abolengo. Y por eso construye su poder con restos. Donde otros usan votos, ella usa cenizas. Donde otros hacen campaña, ella organiza misas. Villarruel no quiere fundar: quiere custodiar. Su Senado no es república: es altar. No promete nación, sino tumba.

Villarruel vela. Ella es la sacerdotisa del hueso. Su sangre no es heredada: es impura y necesita ser consagrada. Lleva en su cuerpo la mancha: mujer, hija de represor, sin abolengo. Y por eso construye su poder con restos.

Tweet

La sangre que Villarruel administra no es militarista: es forense. No es moderna: es litúrgica. No es la del ejército productivo de San Martín, sino la del Cabral negro, sin herederos, sin apellido, sacrificado por otro. Ella toma ese gesto —el de morir por el Padre— y lo repite. Pero no para engendrar futuro: para quedarse custodiando el pasado. Es la hija bastarda que solo puede redimirse velando muertos.

En este juego litúrgico, el kirchnerismo ya no tiene lugar. Cristina y Néstor, en su momento, organizaron un linaje simbólico de la sangre: canonizaron a las Madres y Abuelas como condesas de la virtud. Convirtieron su dolor en legitimidad, su pérdida en bandera, su duelo en política. El nieto buscado era también el heredero del proyecto nacional. Pero ese futuro hoy parece clausurado. El nieto ya no aparece. La abuela ya no habla. El linaje progresista se extinguió no por derrota, sino por saturación. El país ya no cree en la fertilidad del duelo. Cree, en todo caso, en su repetición sin promesa.

El linaje progresista se extinguió no por derrota, sino por saturación simbólica. El país ya no cree en la fertilidad del duelo. Cree, en todo caso, en su repetición sin promesa.

Tweet

Villarruel recoge esa saturación y la invierte. Si el kirchnerismo era patriarcalismo futurista, ella propone matriarcalismo funerario. No madre de hijos, sino madre de tumbas. No presidenta: viuda. En esto se emparenta con Isabel Perón, otra mujer que gobernó desde el altar, entre cadáveres y velatorios. Ambas fueron acusadas de ilegítimas. Ambas respondieron con misas. Ambas eligieron el silencio, la negrura, la invocación. Pero Villarruel tiene algo más: la escena senatorial. El mármol, la liturgia, el telón institucional que le permite convertir su debilidad en rito.

Villarruel recoge esa saturación y la invierte. Si el kirchnerismo era patriarcalismo futurista, ella propone matriarcalismo funerario. No madre de hijos, sino madre de tumbas. No presidenta: viuda. En esto se emparenta con Isabel Perón.

Tweet

Todos los actores del presente argentino comparten una cosa: creen en el sacrificio. Lo que cambia es el Dios. Milei sacrifica al algoritmo. Bullrich, al apellido. Villarruel, a la Patria. Pero esa patria no es fértil: es espectral. No se produce: se vela. En este régimen, la sangre no circula. Se coagula. Se convierte en reliquia.

¿Y qué significa Alvear en este mapa? No es solo un apellido. Es una forma de propiedad simbólica. El linaje aristocrático en Argentina no es productivo: es extractivo. No es militarista: es cívicamente punitivo. No manda: administra exclusión. Bullrich es su heredera fallida. Tiene sangre, pero no altar. Por eso grita. Por eso golpea. Por eso recurre al Mossad: porque no tiene templo propio.

El linaje aristocrático en Argentina es extractivo. No es militarista: es cívicamente punitivo. No manda: administra exclusión. Bullrich es su heredera fallida. Tiene sangre, pero no altar. Por eso golpea y recurre al Mossad: porque no tiene templo propio.

Tweet

Villarruel lo entendió. No puede competir con Bullrich en linaje, ni con Milei en algoritmos. Pero puede vencerlos con algo más poderoso en este país: el cadáver nacional. Ese que nadie quiere tocar, pero todos veneran. Ese que ya no habla, pero organiza. Ese que ya no vive, pero ordena. Y así, mientras Milei gobierna con fórmulas y Bullrich con balas, Villarruel gobierna con restos.

La pregunta ya no es quién gobierna, sino quién vela. Quién administra la sangre. Quién decide qué cuerpo tiene valor. La política argentina ha abandonado el futuro. Ya no se trata de producir nada. Se trata de quién es digno de ser sacrificado. Y en esa misa oscura, Villarruel lleva la ventaja. Porque ella sí cree. Porque ella sí vela. Porque ella, y sólo ella, sabe lo que vale un hueso.

En esa misa oscura, Villarruel lleva la ventaja. Porque ella sí cree. Porque ella sí vela. Porque ella, y sólo ella, sabe lo que vale un hueso.

Tweet

villarruel as President: Bastard Blood and the Corrientes Mass of the Black Hero

This weekend, Vice President Victoria Villarruel traveled to Corrientes to symbolically deposit the ashes of Sergeant Cabral, the popular hero who, according to the founding myth, gave his life to save San Martín. The gesture was more than a tribute: it was a ritual sacrifice. In parallel, Villarruel publicly denounced the digital trolls of Javier Milei and the owner of La Derecha Diario, accusing them of persecuting her for having supported the Radical candidate in the province, defying the will of La Libertad Avanza. In that double gesture—one funerary, the other judicial—lies the core of her strategy: to consolidate power not through policy or futurity, but through the administration of the dead.

What’s unfolding is not a debate about law or institutions, but about corpses and liturgies. Blood has returned to the center of political power—not as a metaphor, but as a technique. In today’s Argentina, violence is not questioned. What matters is who administers it, for which god, and with which body. Milei, Bullrich, and Villarruel no longer represent ideologies. They embody rituals of sacrifice.

Javier Milei sacrifices without an altar. His violence is silent, eugenic, automated. In his vision, blood is not offered—it is deleted. His government does not produce martyrs, only disposables. No graves, no plaques, no mourning—just data. Like a digital viceroy, he executes the will of international capital and erases whatever does not produce. His relationship to blood is clinical, obsessive, almost scientific. He does not believe in sacrifice as redemption, but in elimination as efficiency. Hence his fascination with cloning, genetic engineering, a future body with no history and no trauma. In his reign, pensioners do not die: they cease to exist.

Patricia Bullrich, on the other hand, believes in blood as lineage. She comes from Alvear—Argentina’s old patrician class. Hers is inherited blood: not offered, but presumed. She doesn’t need relics, because she is already the heiress. But this blood is sterile. It does not create, does not organize, does not fertilize. It punishes. Bullrich represents a decadent, sadistic liberalism: chaotic repression, drugged police, a vigilante state. Her connection to the Mossad reveals another kind of liturgy: violence without redemption, without promise, without community. Pure punishment, pure control, pure survival of the ruling class. Like any aristocrat, she kills without knowing whom she serves.

Villarruel enters through a different door. She doesn’t execute. She doesn’t optimize. She mourns. She is the priestess of the bone. Her blood is neither inherited nor erased—it is bastard blood in need of consecration. Her body carries the stain: a woman, daughter of a repressor, without noble lineage. That is why she builds power through remains. Where others use votes, she uses ashes. Where others campaign, she holds mass. Villarruel does not want to found a nation: she wants to custody a corpse. Her Senate is not a republic—it is an altar. She does not promise a future—she administers a tomb.

The blood Villarruel manages is not military—it is forensic. Not modern, but liturgical. It’s not the productive blood of San Martín’s army, but the blood of the Black Cabral: no heirs, no surname, sacrificed for someone else. She takes that gesture—dying for the Father—and repeats it. But not to engender future, to remain guarding the past. She is the bastard daughter who can only redeem herself by tending to the dead.

Here, the progressive narrative collapses. Cristina and Néstor once constructed a symbolic lineage through blood: they canonized the Mothers and Grandmothers of Plaza de Mayo as countesses of virtue. Their pain became legitimacy, their loss a banner, their mourning a political project. The missing grandchild was also the heir of the nation. But that future today seems foreclosed. The grandchild no longer appears. The grandmother no longer speaks. The progressive lineage didn’t die—it saturated itself. The nation no longer believes in the fertility of mourning. It believes, if anything, in its unredeemable repetition.

Villarruel seizes that exhaustion and inverts it. If Kirchnerism was patriarchal futurism, she proposes funerary matriarchy. Not a mother of children—but a mother of tombs. Not a president—but a widow. In this, she resembles Isabel Perón: another woman who governed among corpses and vigils. Both were deemed illegitimate. Both answered with masses. Both chose silence, black garments, and invocation. But Villarruel has something else: the Senate as stage. The marble, the ritual, the institutional backdrop that lets her turn weakness into rite.

All political figures in today’s Argentina believe in sacrifice. What changes is the deity. Milei sacrifices to the algorithm. Bullrich to the surname. Villarruel to the Nation. But this nation is not fertile—it is spectral. It is not produced—it is mourned. Blood no longer flows. It coagulates. It becomes relic.

And what does Alvear mean in this landscape? It’s not just a name. It is a symbolic form of property. Argentina’s aristocracy is not productive—it is extractive. Not militarist—but civically punitive. It doesn’t rule—it excludes. Bullrich is its failed heiress. She has blood, but no altar. That’s why she shouts. That’s why she hits. That’s why she invokes the Mossad: she has no temple of her own.

Villarruel understands this. She cannot compete with Bullrich in lineage, nor with Milei in data. But she can beat them with something far more powerful in Argentina: the national corpse. The one no one dares touch, but everyone worships. The one that no longer speaks, but still commands. The one that no longer lives, but still organizes. And so, while Milei governs with formulas and Bullrich with bullets, Villarruel governs with bones.

The question is no longer who governs—but who mourns. Who handles the blood. Who decides what body has value. Argentine politics has abandoned the future. It no longer seeks to produce anything. It seeks only to decide who deserves to be sacrificed. And in that dark mass, Villarruel leads. Because she believes. Because she mourns. Because she alone understands the worth of a bone.

Deja una respuesta