Scroll Down for the English Version

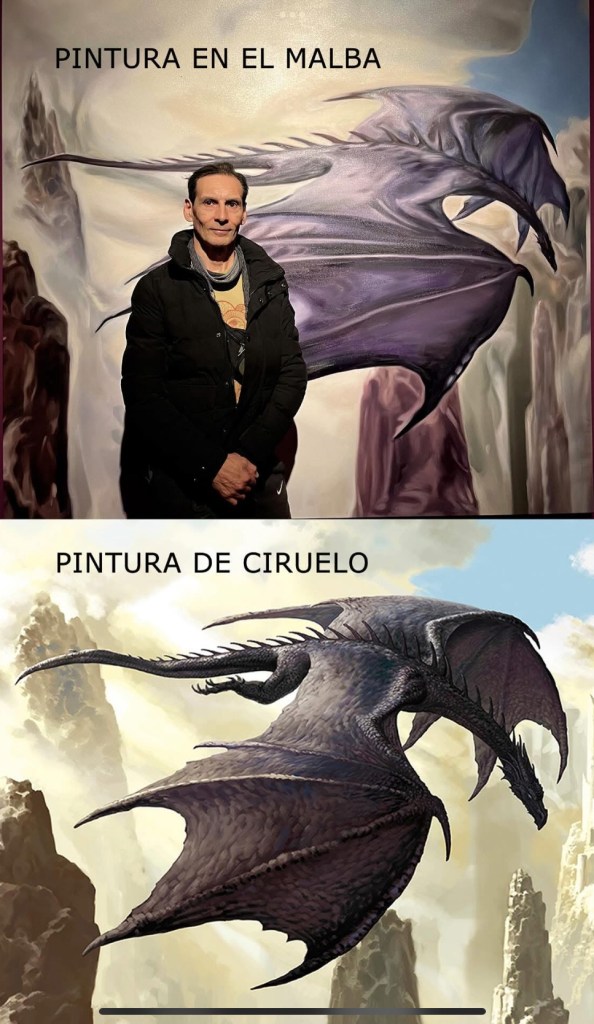

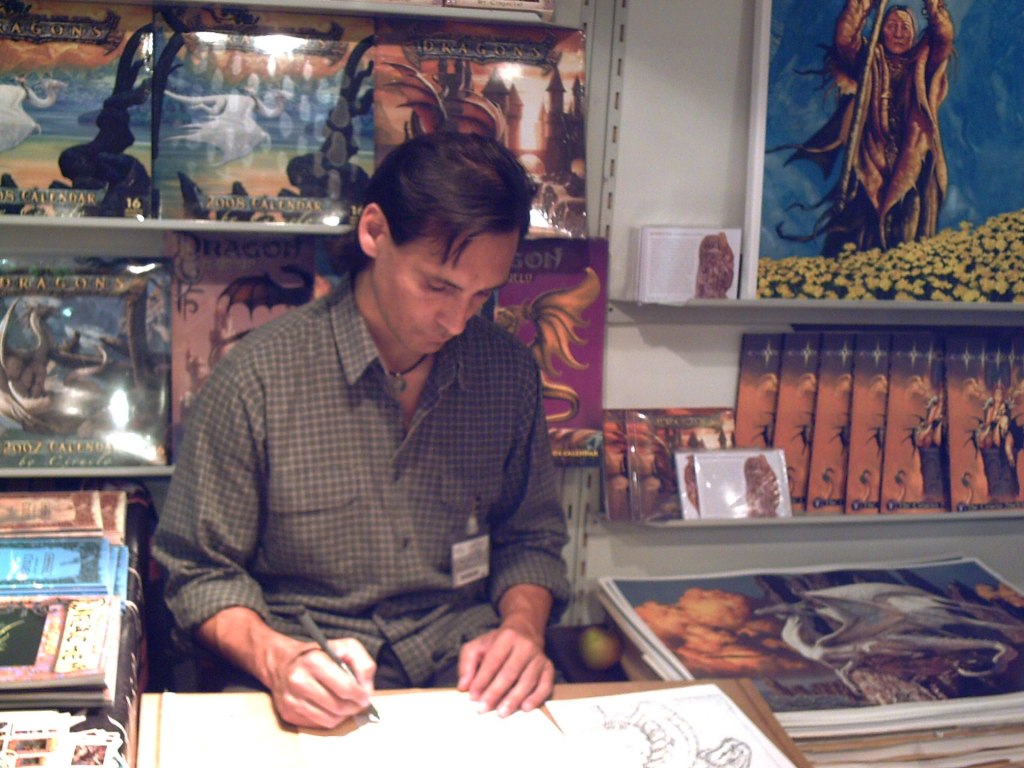

El artista de “fantasy” Ciruelo Cabral denunció en redes la similitud entre su obra Dragon Caller (2005) y una pintura con dragón exhibida en la muestra de Carrie Bencardino en el MALBA. Pronto se convirtió en un escándalo cubierto por los medios nacionales.

Tweet

El desentierro del diablo, primera exposición institucional de Carrie Bencardino (Buenos Aires, 1993), en MALBA, Sala 1 – Nivel -1, del 12 de julio al 13 de octubre de 2025. Con curaduría de Carlos Gutiérrez. Es, sobre todo, pintura (con atmósfera de “casi bar, casi cine, casi club”). El texto curatorial parte de una “crisis de la imaginación” y propone reabrir “la imaginación política”: escenas que oscilan entre lo real y lo fantástico, con objetos y figuras monumentalizadas, bordes difusos y climas sintéticos. Bencardino trabaja formatos grandes, superficies suaves/casi aerografiadas y un ‘bestiarix/objetería’ que mezcla archivo pop y lo onírico. La página del museo y las reseñas, sitúan la muestra en ese cruce de fantasía y política.

Mi premisa es que la exposición sostiene su tesis en piezas como El mal, entre muchas otras pero, el “dragón”, en particular, abre un problema que merece la atención de este blog. La crítica no va a ser la de la ofensa por el plagio sino primero intentar comprender desde dentro de la obra de la artista cuáles son las operaciones formales y cómo su propuesta visual dialoga con la tesis curatorial. Debemos distinguir entre apropiación transformadora y calco, sobre todo cuando hay coincidencias estructurales tan obvias. Es difícil de creer que una artista que pinta al nivel del de ella, necesite plagiar o calcar. Por eso no adelantemos juicio y síganme… los que puedan porque esta no es una crítica de ‘ofendidito’ sino que busca entender del arte en este momento particular de la Argentina.

Debemos distinguir entre apropiación transformadora y calco, sobre todo cuando hay coincidencias estructurales tan obvias. Es difícil de creer que una artista que pinta al nivel del de ella, necesite plagiar o calcar

Tweet

Dragón 1

Si el “dragón” aparece como una visión que irrumpe entre vigilia y sueño, debería traer marcas de una grieta: fallas de anatomía, perspectiva torcida, costuras entre figura y fondo, un título que rompa el tiempo lineal. Solo así se leería como fantasma de un imaginario masculino reabsorbido en un mundo onírico propio (virgen/dragón como polos que ya no obedecen al guión épico del “macho” sino a su desprogramación íntima). Sin esas grietas formales, la pieza no “posee” el símbolo: lo repite. Ahí la política del sueño se vuelve tenue y lo que queda es nostalgia empaquetada.

Dragón 2

El déjà vu funciona como método solo si hay transformación estructural (escala, cropping, ritmo, función del motivo). Si contorno, pose y anatomía calcan repertorios del fantasy, la operación deja de ser cita para volverse obra derivada; se cae la ética de la apropiación y, con ella, la promesa política. El “escándalo” podría operar como táctica —activar debate sobre autoría, canon, género—, pero en clave de Mark Fisher corre el riesgo de ser capitalizado por la economía de atención, donde lo nuevo es lo que shockea y no la forma. Si la pieza no muestra desplazamiento visible, su política es circulación, no imaginación.

El mal es un sillón.

En El mal el procedimiento se afirma: aislamiento y monumentalización del objeto doméstico, tratamiento casi aerografiado y sensualidad de superficie que vuelven siniestro lo familiar. No hay ilustración de una idea: hay desplazamiento alegórico (el mueble deviene poder, deseo, amenaza) y una atmósfera que anuda el eje virgen/dragón sin nombrarlo: lo devocional y lo monstruoso laten como climas, no como citas. Aquí la muestra cumple su tesis: produce mundo y liga fantasía y política por vía de materialidad, no de ruido mediático.

En el texto de la muestra la curaduría propone tres avenidas de sentido: una crisis de la imaginación en el presente; la necesidad de reabrir la imaginación política para “producir mundos”; y la coexistencia de escenas que funcionan en un umbral entre lo real y lo fantástico, como si se asistiera a una respiración alternada entre estar despierto y estar soñando. El punto de partida —la “crisis”— no me interesa como lamento benjaminiano por el aura perdida, ni como diagnóstico generalista sobre algoritmos y pantallas; me interesa como síntoma formal porque estamos en el MALBA. Allí donde los repertorios visuales se convierten en plantillas —poses, anatomías, climas, paletas que circulan con una facilidad admirable y una pobreza inquietante—, una exposición que promete “producir mundos” tiene que dejar trazas de ruptura: no “originalidad” como fetiche, sino operaciones verificables que cambien el régimen de lectura.

Allí donde los repertorios visuales se convierten en plantillas —poses, anatomías, climas, paletas que circulan con una facilidad admirable y una pobreza inquietante—, una exposición que promete “producir mundos” tiene que dejar trazas de ruptura

Tweet

Cuando hablo de “operaciones”, hablo de “decisiones” que se ven y se sienten: una composición que no es la esperable; una escala que desbarata la ergonomía del ojo; un cropping que reescribe la jerarquía de las formas; un espesor de materia que no ilustra sino que empuja significados; un montaje que no cuelga obras sino que arma leyes internas, recurrencias, desvíos. En ese terreno, El mal demuestra cómo el surrealismo no es aquí la coartada de la fantasía sino la política del desplazamiento: lo doméstico convertido en potencia siniestra a fuerza de técnica, luz y tacto. En cambio, el “dragón” concentra todas las preguntas porque enfrenta de modo frontal los límites entre la cita y el calco, entre apropiación transformadora y reproducción de repertorio.

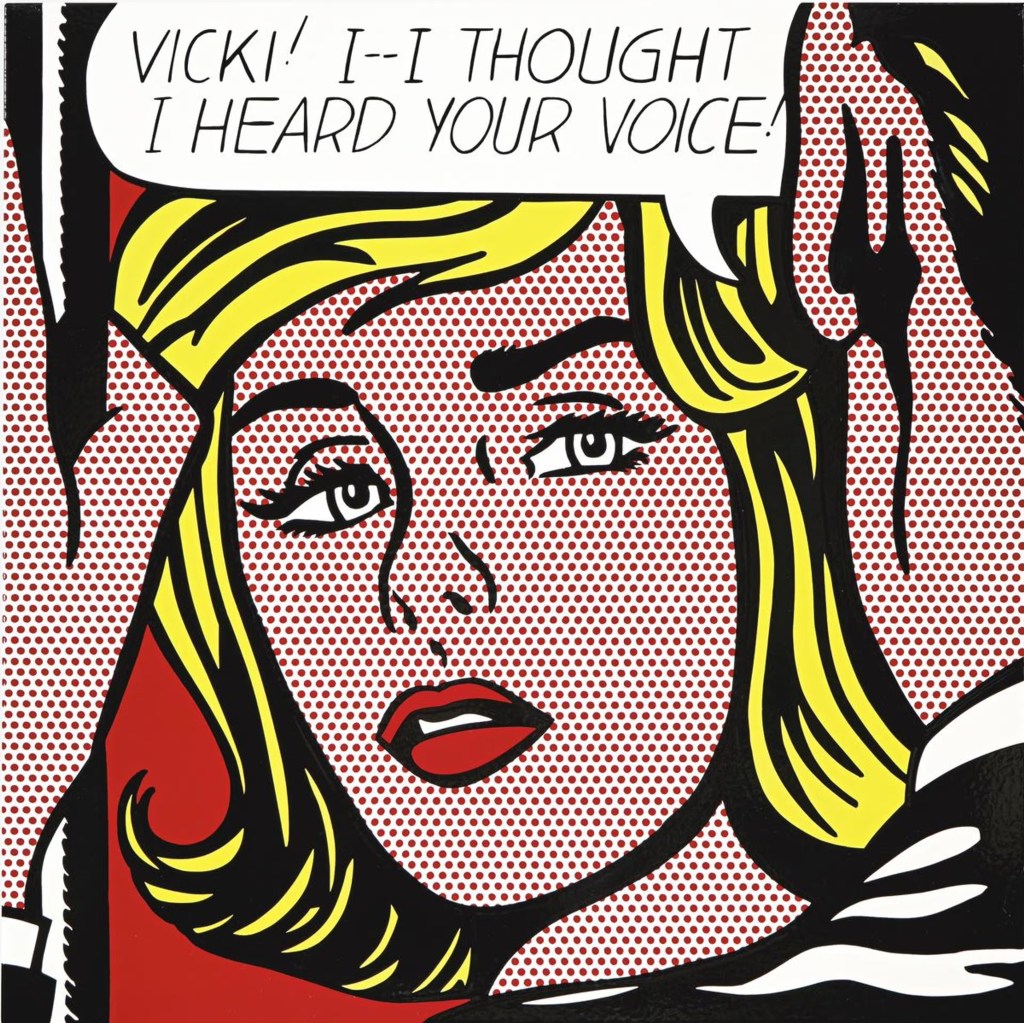

La segunda tesis —imaginar políticamente— sólo se sostiene si el mundo que se construye supera la suma de motivos. Es decir: no alcanza con poner en juego íconos que portan lecturas fuertes (una virgen, un dragón) si esos signos no se recodifican dentro de una gramática propia. El Arte Pop norteamericano nos enseñó que se puede pensar con imágenes ajenas, siempre que se altere el mecanismo: Lichtenstein no “copiaba” viñetas, las convertía en pintura mediante escala, trama y corte. El Arte Postmoderno de la Revista October como el de Sherrie Levine, por ejemplo, no “robaba” fotografías, desestabilizaba la autoría; Sturtevant repetía para desnudar la repetición. Aquí, si el dragón pretende ser una apropiación crítica de un imaginario masculino, tiene que cambiar de régimen: pasar de fetiche de potencia a talismán ambiguo, de proeza épica a residuo onírico, de signo ostentoso a bulto uncanny. Si eso no ocurre, la política queda enunciada; la respuesta se disuelve en la comodidad del reconocimiento.

No alcanza con poner en juego íconos que portan lecturas fuertes si esos signos no se recodifican dentro de una gramática propia. El Pop nos enseñó que se puede pensar con imágenes ajenas, siempre que se altere el mecanismo.

Tweet

La tercera línea —lo real y lo fantástico— exige precisión clínica. Lo fantástico no es un reino temático (“pintar monstruos”) sino una lógica de aparición. En Conversación la confluencia de cuerpos y cielo sintético suspende la narrativa y desplaza la escena hacia una suerte de habitación mental, donde lo real se impregna de un clima que no es psicologismo sino atmósfera: la atmósfera hace política porque altera el régimen de atención. Allí el surrealismo no es estilo, es método: el mundo no copia lo real, lo deriva. Si el “dragón” quiere habitar la misma lógica, tiene que entrar por la grieta del sueño, no por la puerta de la ilustración; tiene que fallar un poco —en anatomía, en perspectiva, en tiempo— para volverse espectral. Sin fallas, sin rarezas, sin tiempo equivocado, sin marcas de montaje, el recuerdo se congela como calco.

Lo fantástico no es un reino temático sino una lógica de aparición. El surrealismo no es estilo, es método: el mundo no copia lo real, lo deriva. Si el “dragón” quiere habitar la misma lógica, tiene que entrar por la grieta del sueño, no por la puerta de la ilustración

Tweet

A partir de lo que acabo de decir, reconstruyo mi discusión —ahora como preguntas que me hago y me contesto— para ordenar el sentido.

¿Estamos frente a una melancolía por el aura perdida o ante una crítica de la plantilla? No veo melancolía. Lo que se tematiza, con mayor o menor precisión según la obra, es la estandarización visual: una circulación de clichés que pre formatea el deseo y automatiza la mirada. Esta crítica no necesita negar lo digital ni demonizar la Inteligencia Artificial; al revés, puede apropiarse del glitch, del fallo, de la combinación improbable para producir desviaciones. La cuestión no es media versus media, sino si hay transformación de repertorios. El mal muestra esa transformación: donde había mueble, hay poder libidinal y amenaza; donde había capitoné, hay piel; donde había función, hay presagio. El “dragón” queda obligado a eso mismo.

¿En qué se diferencia esta crítica del Pop, que también trabajó con repertorios masivos? En que aquí no basta la cita brillante ni la consagración del look. El Pop clásico convertía el bajo en alto mediante operaciones formales contundentes: escala que arrasa, trama que materializa, corte que recompone la figura. Si la muestra quiere diagnosticar la crisis actual, no puede quedarse con la superficie Pop de la repetición; tiene que mostrar la ingeniería de la mutación. Lo que en Lichtenstein era trama, aquí debería ser piel de pintura; lo que en Lichtenstein era cropping, aquí debería ser torsión de la escena; lo que en Lichtenstein era escala, aquí debería ser régimen espacial que nos expulse de la contemplación cómoda. Sin eso, la pieza se acomoda al algoritmo: gusta porque ya gustaba. Si la pieza transformara el original a simple vista, el proceso sería irrelevante. Pero cuando las coincidencias son tantas, la artista tiene que mostrar el proceso de intervención para distinguir entre influencia legítima, apropiación crítica y calco.

Si la muestra quiere diagnosticar la crisis actual, no puede quedarse con la superficie Pop de la repetición; tiene que mostrar la ingeniería de la mutación.

Tweet

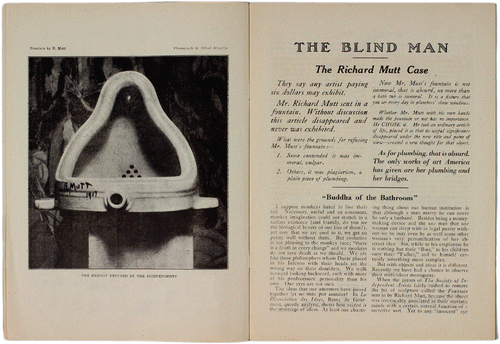

¿Y Marcel Duchamp? ¿No alcanza con declarar apropiación, como en el ready-made? No: el ready-made desplazaba un objeto de un régimen de uso a un régimen de arte mediante una operación conceptual radical y una institución dispuesta a tolerarla. Tomar una imagen casi idéntica de un repertorio circulante y volver a pintarla no es, en sí mismo, ready-made; tampoco es objet trouvé surrealista, que pedía azar, choque, montaje. Para que funcione, la imagen tomada tiene que nacer de un gesto que cambie su función simbólica, su tiempo interno, su inscripción en un mundo. Si no, se queda en derivación.

¿Se puede politizar la estandarización por hipérbole y escándalo mediático? Sí, se puede y a veces hay que hacerlo. Pero entonces hay que ser honesto con la tesis: ya no se trata de “producir mundos” sino de usar el sistema —museo, prensa, redes— como cámara de eco para tensionar propiedad intelectual, canon y género. Es válido, pero es otro proyecto artístico totalmente diferente: una obra cuyo medio es la circulación y cuyo valor es el conflicto. Fisher ayuda a verlo: el riesgo es que el sistema absorba el conflicto como contenido, lo empaquete, lo monetice, y nada cambie en la forma de ver. La política no sería entonces la transformación sensible sino el engagement. Yo no desprecio ese arte de circulación; pido que se asuma como tal y que no se presente como invención onírica si no lo es. El texto promete una aventura de imaginación política y lo que se ve en sala no muestra las operaciones que la harían posible. En El mal la respuesta aparece porque el procedimiento material produce extrañamiento: no hay un sillón representado, hay un dispositivo afectivo que exuda dominio y deseo. En el “dragón”, si todo se apoya en el reconocimiento de una forma conocida —el contorno, la pose, la anatomía de siempre—, la imaginación política queda en suspenso. No es una cuestión moralista de “originalidad”: es una cuestión formal de transformación.

En el “dragón”, si todo se apoya en el reconocimiento de una forma conocida, la imaginación política queda en suspenso. No es una cuestión moralista de “originalidad”: es una cuestión formal de transformación.

Tweet

¿Puede leerse el “dragón” como recuerdo, no como copia? Esta es la hipótesis hauntológica que me interesa. El recuerdo onírico no reproduce; deforma, condensa, desplaza. Un dragón recordado no tiene por qué costurar igual las alas al torso, ni sentarse con la misma tensión de lomo, ni mirar desde el mismo ángulo; en todo caso, se descuadra, se dobla, se mezcla con otro animal, trae un pedazo de otro cuadro. Si la pieza deja ver esas huellas —costuras raras, anatomías desplazadas, tiempos cruzados—, el recuerdo existe como operación. Si no, el recuerdo es un nombre elegante para lo que el ojo capta enseguida: más de lo mismo.

Leonora Carrie-ngton Punk?

¿Y si esto fuera un gesto feminista —“robarle el dragón al macho”— para reescribir un imaginario patriarcal desde un micromundo onírico? Esta es una hipótesis potente en el caso de esta artista pero para sostenerla, necesito ver el cambio de régimen: el dragón convertido en objeto, mascota, exvoto; el dragón mirado por un sujeto que no es la épica del héroe sino la ambivalencia de una virgen que ya no es presa; el dragón despotenciado, erotizado, ridiculizado, domesticado o devuelto a la infancia de la pesadilla. No alcanza con firmarlo en otro soporte ni con cambiar la atmósfera. En el mejor Carrington, el bestiario no es cita: es ley de un mundo que le pertenece. Ese es el umbral. ¿Dónde entra Fisher, más allá del riesgo de cooptación? Fisher escribe sobre la sensación de clausura —no hay alternativa— y sobre cómo el presente vive atormentado por futuridades que no ocurrieron. El museo, en este marco, puede ser refugio o trampa. Refugio si aloja espectros para exponer su desgaste, si convierte las imágenes gastadas en pruebas de una pérdida cultural que hay que procesar. Trampa si recicla esos espectros como privilegio institucional. La diferencia la decide la operación visible: si la obra induce la rareza —ese weird/eerie que saca a las cosas de su sitio—, hay duelo; si solo reitera, hay nostalgia. ¿Dónde están las vírgenes y cómo dialogan con los dragones? La muestra —desde su texto y su recepción— opera con ese eje. La virgen no es aquí el remanso piadoso de la iconografía católica; es un clima: un modo de suspender lo mundano y de instaurar una atención distinta. Si el dragón entra como polo complementario, la pregunta es quién manda. En Carrington, lo femenino gobierna el bestiario; en cierta tradición fantasy, el monstruo gobierna a la doncella. Si el mundo de esta exposición se inclina hacia lo primero, el dragón debe obedecer leyes nuevas.

¿Qué pasa con Conversación en esta grilla? Pasa que, a diferencia del “dragón”, se sustrae a la plantilla desde la composición y la atmósfera. El formato apaisado, el juego con el vacío central, esa nube púrpura que no explica nada pero lo impregna todo, empujan a otra temporalidad. No hay reconocimiento complaciente: hay deriva. No es un cuadro para thumbnail; es un cuadro de feria artesanal. Esa elección formal —hacer de la escena un clima— es política porque nos arranca de la hipereficiencia de la atención.

¿El “escándalo” como política puede mejorar la obra? Puede. Pero exige que el escándalo vuelva sobre la forma. Si la polémica obliga a reescribir fichas, a creditar fuentes, a ajustar curadurías, a pensar el canon fantasy desde el museo, entonces cambia la lectura institucional y social de la pieza. Si la polémica se consume como trending, la obra se convierte en un episodio del feed. Los museos —y los artistas— no siempre controlan ese desenlace; pero pueden tomar una posición, y la posición se nota en el texto de sala, en el recorrido, en cómo responden públicamente. ¿Se puede pedir a una exposición que haga todo eso? Sí, si se promete “producir mundos”. Un mundo exige leyes, y las leyes se fabrican con decisiones. A veces una sola obra basta para sostenerlas —El mal es mi caso—; a veces una sola obra alcanza para ponerlas en duda —el “dragón”—. La evaluación no es moral, es interna al dispositivo: si la muestra regula con claridad sus dos energías —devocional y monstruosa—, si el surrealismo aparece como método y no como decorado, si lo onírico se reconoce en la textura y no en el catálogo de motivos, entonces el mundo se sostiene; si no, queda la crisis que se enuncia y se perpetúa.

¿Dónde queda, en todo esto, la relación entre realidad y fantasía? Justo en el umbral. La fantasía es poderosa cuando perfora lo real, y esa perforación se ve en el cuerpo de la pintura y en la gramática de la sala. Aislar, monumentalizar, aerografiar, erotizar la superficie: son técnicas para abrir un pliegue sin caer en el efectismo. El problema del “dragón” es que, si no se pliega, si no se hiere un poco, no transpira fantasía; transpira repertorio. Y el repertorio, en tiempos de economía de la atención, triunfa por default. ¿Puedo entonces sostener ambas lecturas —espectral y feminista— del “dragón” sin contradecirme? Puedo ver si se verifica el desvío. La hauntología pide fallas con sentido; el feminismo pide cambio de régimen simbólico. Si esas marcas aparecen, la pieza puede ser el fantasma de un imaginario masculino apropiado por un mundo femenino/onírico. Si no, la pieza es exactamente lo que parece: una reiteración que confía en el poder de la cita sin asumir su costo.

¿Y el MALBA? ¿Refugio o cooptación? Las instituciones no son esencias; son decisiones acumuladas. Esta exposición muestra que hay, al menos, un procedimiento capaz de sostener la promesa —El mal— y un punto crítico que puede dinamitarla —el “dragón”—. El museo puede tomar el conflicto como oportunidad: explicitar el estatuto de las fuentes, reforzar el dossier de proceso, afinar el texto que justifica el lugar de lo fantástico en el presente. Si lo hace, la exposición no pierde; gana densidad. Si no, confirmará que la economía de atención manda, también en las salas.

¿Y el MALBA? ¿Refugio o cooptación? Las instituciones no son esencias; son decisiones acumuladas. El museo puede tomar el conflicto como oportunidad. Si lo hace, la exposición no pierde; gana densidad.

Tweet

Cierro con una constatación práctica: mirar obras en el modo “mundo” exige tiempo y fricción. El mal hace trabajar al ojo; Conversación hace respirar más lento; el “dragón” —si no se demuestra su transformación— acelera la recompensa del reconocimiento. La muestra se juega en ese ritmo. Si la promesa es salir de la plantilla, las piezas que ya lo hacen son el estándar con el que mediremos todo lo demás. Y si el “dragón” quiere ser fantasma y no calco, tiene un camino claro: deformar, desplazar, reescribir. Sin esas operaciones, el sueño no llega; llega el thumbnail. Y ahí no hay imaginación política, hay una mini-denuncia con cierta vagancia tanto material como intelectual.

Plagiarism or Appropriation?: Bencardino, Ciruelo, and the Politics of the Ready-Made and the Thumbnail (ENg)

The fantasy artist Ciruelo Cabral posted on social media about the similarity between his work Dragon Caller (2005) and a dragon painting shown in the exhibition. It quickly turned into a scandal covered by national media.

El desentierro del diablo [Unearthing the Devil], the first institutional exhibition of Carrie Bencardino (Buenos Aires, 1993), is on view at MALBA, Sala 1 – Level -1, from July 12 to October 13, 2025. Curated by Carlos Gutiérrez. It is, above all, a painting show (with an atmosphere of “almost bar, almost cinema, almost club”). The curatorial text starts from a “crisis of imagination” and proposes to reopen political imagination: scenes that oscillate between the real and the fantastic, with monumentalized objects and figures, soft edges, and synthetic atmospheres. Bencardino works in large formats, with smooth/almost airbrushed surfaces and a bestiarix/objetería—a bestiary/object-world—that mixes pop archives with the oneiric. The museum’s page and reviews place the show at that crossroads of fantasy and politics.

My premise is that the exhibition does sustain its thesis in works like El mal, among several others; however, the “dragon” in particular raises a problem that merits this blog’s attention. The critique will not be about taking offense at plagiarism, but about first trying to understand from within the artist’s work what the formal operations are and how her visual proposal speaks to the curatorial thesis. We need to distinguish between transformative appropriation and tracing, especially when there are such obvious structural coincidences. It is hard to believe that an artist who paints at her level would need to plagiarize or trace. So let’s not rush to judgment, and follow me—those who can— because this is not an “outraged” critique; it tries to understand art in this particular moment in Argentina.

Dragon (spectral/feminist hypothesis).

If the “dragon” appears as a vision erupting between wakefulness and sleep, it should carry marks of deviation: anatomical glitches, skewed perspective, visible seams between figure and ground, a title that breaks linear time. Only then would it read as a ghost of a masculine imaginary reabsorbed into a oneiric world of its own (virgin/dragon as poles that no longer obey the epic script of the “male” but its intimate deprogramming). Without those formal fissures, the piece doesn’t “possess” the symbol: it repeats it. At that point the politics of dreaming thins out and what remains is packaged nostalgia.

Dragon (déjà vu/failed Lichtenstein and the attention economy).

Déjà vu works as a method only if there is structural transformation (scale, cropping, rhythm, function of the motif). If contour, pose, and anatomy trace fantasy repertoires, the operation stops being citation and becomes a derivative work; the ethics of appropriation collapses and with it the political promise. The “scandal” could operate tactically—sparking debate about authorship, canon, gender—but in Fisher’s key it risks being captured by the attention economy, where novelty is the uproar, not the form. If the piece shows no visible displacement, its politics is circulation, not imagination.

El mal (isolated object, surrealism, and an uncanny that works).

In El mal [Evil] the procedure holds: isolation and monumentalization of the domestic object, an almost airbrushed treatment and surface sensuality that render the familiar uncanny. There’s no illustration of an idea: there is allegorical displacement (the piece of furniture becomes power, desire, threat) and an atmosphere that knots together the virgin/dragon axis without naming it: the devotional and the monstrous pulse as climates, not citations. Here the show delivers on its thesis: it builds a world and links fantasy and politics through materiality, not media noise.

From this opening, it’s worth returning to the show’s explicit theses—not to repeat them, but to test them in the gallery. The curatorship proposes three lines: a crisis of imagination in the present; the need to reopen political imagination in order to “produce worlds”; and the coexistence of scenes that operate on a threshold between the real and the fantastic, as if we were witnessing an alternate breathing between being awake and being asleep. The starting point—the “crisis”—doesn’t interest me as a Benjaminian lament for the lost aura, nor as a catch-all diagnosis about algorithms and screens; it interests me as a formal symptom. Wherever visual repertoires harden into templates—poses, anatomies, climates, palettes that circulate with admirable ease and troubling poverty—an exhibition that promises to “produce worlds” must leave traces of rupture: not “originality” as fetish, but verifiable operations that change the reading regime.

When I speak of operations, I mean decisions you see and feel: a composition that isn’t the expected one; a scale that throws off the eye’s ergonomics; a cropping that rewrites the hierarchy of forms; a thickness of matter that doesn’t illustrate but presses meaning; a montage that doesn’t just hang works but forges internal laws, recurrences, deviations. On that ground, El mal shows how surrealism here isn’t a pretext for fantasy but a politics of displacement: the domestic turned sinister power through technique, light, and touch. By contrast, the “dragon” concentrates all the questions because it confronts, head on, the border between citation and tracing, between transformative appropriation and reproduction of repertoire.

The second thesis—imagining politically—only holds if the world that’s built exceeds the sum of its motifs. That is: it’s not enough to deploy icons loaded with strong readings (a virgin, a dragon) if those signs aren’t recoded within a grammar of their own. Pop taught us that one can think with borrowed images, as long as one alters the mechanism: Lichtenstein didn’t “copy” comic panels—he turned them into painting through scale, screen, and cut; Sherrie Levine didn’t “steal” photographs—she destabilised authorship; Sturtevant repeated in order to lay bare repetition. Here, if the dragon aims to be a critical appropriation of a masculine imaginary, it has to change regime: from potency fetish to ambiguous talisman, from epic prowess to oneiric residue, from ostentatious sign to uncanny lump. If that doesn’t happen, the politics are announced; the response dissolves into the comfort of recognition.

The third line—the real and the fantastic—demands clinical precision. The fantastic isn’t a thematic realm (“painting monsters”) but a logic of appearance. In Conversación the convergence of bodies and synthetic sky suspends narrative and shifts the scene toward a kind of mental room, where the real is saturated by a climate that isn’t psychologism but symbolic weather: atmosphere does politics because it alters the attention regime. There surrealism isn’t a style; it’s a method: the world doesn’t copy the real; it derives it. If the “dragon” wants to inhabit that same logic, it needs to enter through the rift of the dream, not the door of illustration; it needs to fail a little—in anatomy, in perspective, in time—to become a ghost. Without failures, without oddities, without wrong time, without marks of montage, the memory freezes as a tracing.

From these theses I reconstruct my discussion—now as questions I ask myself and answer—to order the sense.

Am I facing a melancholy for the lost aura or a critique of the template? I don’t see melancholy. What’s thematized—more or less precisely depending on the work—is visual standardization: a circulation of clichés that pre-formats desire and automates the gaze. This critique doesn’t need to deny the digital or demonize AI; on the contrary, it can appropriate glitch, failure, improbable combination to produce deviations. The point isn’t medium versus medium, but whether there is transformation of repertoires. El mal shows that transformation: where there was furniture, there is libidinal power and threat; where there was tufting, there is skin; where there was function, there is foreboding. The “dragon” is bound to the same.

How does this differ from Pop, which also worked with mass repertoires? Here, the flashy citation or the consecration of the look doesn’t suffice. Classic Pop turned low into high through forceful formal operations: scale that overwhelms, screen that materializes, cut that recomposes the figure. If the show wants to diagnose today’s crisis, it can’t park at Pop’s surface of repetition; it has to show the engineering of mutation. What was screen in Lichtenstein should be skin of paint here; what was cropping there should be torsion of the scene here; what was scale there should be a spatial regime here that boots us out of comfortable contemplation. Without that, the piece settles into the algorithm: it pleases because it already pleased.

And Duchamp? Isn’t declaring appropriation, as in the ready-made, enough? No. The ready-made shifted an object from a use regime to an art regime through a radical conceptual operation and an institution willing to tolerate it. Taking an almost identical image from a circulating repertoire and painting it again is not, in itself, a ready-made; nor is it the surrealist objet trouvé, which demanded chance, shock, montage. To work, the taken image must be born from a gesture that changes its symbolic function, its internal time, its inscription in a world. Otherwise it remains a derivation.

Can standardization be politicized through hyperbole and media scandal? Yes, and sometimes it must be. But then one must be honest about the thesis: it’s no longer about “producing worlds” but about using the system—museum, press, networks—as an echo chamber to stress intellectual property, canon, and gender. That’s valid, but it’s another work: a work whose medium is circulation and whose value is conflict. Fisher helps here: the risk is that the system absorbs the conflict as content, packages it, monetizes it, and nothing changes in how we see. Politics would then be not sensory transformation but engagement. I don’t despise that art of circulation; I’m asking that it be owned as such, and not presented as oneiric invention if it isn’t.

What does “announcement without response” mean? It means the text promises an adventure of political imagination and what’s seen in the gallery doesn’t show the operations that would make it possible. In El mal the response appears because the material procedure produces estrangement: there isn’t a chair represented; there’s an affective device exuding domination and desire. In the “dragon,” if everything leans on the recognition of a familiar form—the same contour, the same pose, the same anatomy—political imagination is suspended. This isn’t a moralistic issue of “originality”; it’s a formal issue of transformation.

Can the “dragon” be read as a memory, not a copy? This is the hauntological hypothesis that interests me. Oneiric memory doesn’t reproduce; it deforms, condenses, displaces. A remembered dragon has no reason to stitch its wings to its torso the same way, to sit with the same tension of back, to look from the same angle; if anything, it goes off-kilter, it doubles, it blends with another animal, it brings a shard from another painting. If the piece lets those traces be seen—odd seams, displaced anatomies, crossed times—the memory exists as an operation. If not, “memory” is a polite name for what the eye notices at once: the same.

And if it were a feminist gesture—“stealing the dragon from the male”—to rewrite a patriarchal imaginary from an oneiric microworld? It’s a strong hypothesis. To sustain it, I need to see the regime change: the dragon turned object, pet, ex-voto; the dragon looked at by a subject who isn’t the hero’s epic but the ambivalence of a virgin who is no longer prey; the dragon depowered, eroticized, ridiculed, domesticated, or returned to the childhood of the nightmare. It’s not enough to sign it on another support or change the atmosphere. In the best Carrington, the bestiary isn’t citation: it’s the law of a world that belongs to her. That’s the threshold.

Where does Fisher come in, beyond the risk of co-optation? Fisher writes about the sense of closure—there is no alternative—and about how the present is haunted by futures that didn’t happen. The museum, in this frame, can be refuge or trap. Refuge if it houses spectres to expose their wear, if it turns worn-out images into evidence of a cultural mourning that must be processed. Trap if it recycles those spectres as premium fan service. The difference is decided by the visible operation: if the work induces weird/eerie rarity that takes things out of place, there is mourning; if it merely reiterates, there is nostalgia.

Are “sketches and process” essential? Not out of a fetish for craft, but as a forensic criterion when there’s a specific accusation. Process doesn’t add nineteenth-century “artisticness”; it adds evidence of deviation: dates, genealogy, proofs of transformation. If the piece transformed at a glance, process would be irrelevant. But when the coincidences are so many, process helps distinguish legitimate influence, critical appropriation, and tracing.

Where are the virgins and how do they dialogue with the dragons? The show—by text and reception—operates with that axis. The virgin here isn’t the soothing haven of Catholic iconography; it’s a climate: a way of suspending the mundane and installing a different attention. If the dragon enters as the complementary pole, the question is who rules. In Carrington, the feminine governs the bestiary; in a certain fantasy tradition, the monster governs the maiden. If this exhibition’s world leans toward the former, the dragon must obey new laws.

What about Conversación in this grid? Unlike the “dragon,” it escapes the template through composition and atmosphere. The widescreen format, the play with central emptiness, that purple cloud that explains nothing but soaks everything, push us into another temporality. There is no comfortable recognition: there is drift. It’s not a painting for a thumbnail; it’s a painting for tired legs. That formal choice—making the scene a climate—is political because it pulls us out of the hyper-efficiency of attention.

Can “scandal” as politics improve the work? It can. But it requires the scandal to return to the form. If the controversy forces rewrites of wall labels, proper crediting of sources, curatorial adjustments, a rethinking of the fantasy canon from within the museum, then the institutional and social reading of the piece changes. If the controversy is consumed as trending, the work becomes an episode in the feed. Museums—and artists—don’t always control that outcome, but they can take a position, and that position is evident in the wall text, in the layout, in how they respond publicly.

Can we ask a show to do all that? Yes, if it promises to “produce worlds.” A world requires laws, and laws are fabricated through decisions. Sometimes a single work suffices to uphold them—El mal in my view; sometimes a single work suffices to call them into question—the “dragon.” The evaluation isn’t moral; it’s internal to the device: if the show clearly regulates its two energies—devotional and monstrous—, if surrealism appears as method and not décor, if the oneiric is legible in texture and not in the motif catalog, then the world holds; if not, the crisis announced is perpetuated.

Where, in all this, is the relation between reality and fantasy? Right at the threshold. Fantasy is powerful when it perforates the real, and that perforation is visible in the body of the painting and in the grammar of the gallery. Isolating, monumentalizing, airbrushing, eroticizing the surface: these are techniques to open a fold without falling into showiness. The problem with the “dragon” is that if it doesn’t fold, if it isn’t wounded a bit, it doesn’t sweat fantasy; it sweats repertoire. And repertoire, in times of the attention economy, wins by default.

So can I sustain both readings—hauntological and feminist—of the “dragon” without contradicting myself? I can if deviation is verified. Hauntology asks for meaningful glitches; feminism asks for a change of symbolic regime. If those marks appear, the piece can be the ghost of a masculine imaginary reappropriated by a feminine/oneiric world. If not, the piece is exactly what it seems: a reiteration that trusts the power of citation without paying its cost.

And MALBA? Refuge or co-optation? Institutions aren’t essences; they are accumulated decisions. This exhibition shows there is, at least, a procedure capable of upholding the promise—El mal—and a critical point that can blow it up—the “dragon.” The museum can take the conflict as an opportunity: make the status of sources explicit, reinforce the process dossier, sharpen the text that justifies the place of the fantastic in the present. If it does, the exhibition doesn’t lose; it gains density. If not, it will confirm that the attention economy rules, even in the galleries.

I close with a practical observation: looking at works in world-mode demands time and friction. El mal makes the eye work; Conversación makes one breathe slower; the “dragon”—if its transformation isn’t demonstrated—accelerates the reward of recognition. The show plays out in that rhythm. If the promise is to depart from the template, the pieces that already do so are the standard by which we’ll measure the rest. And if the “dragon” wants to be ghost and not tracing, its path is clear: deform, displace, rewrite. Without those operations, the dream doesn’t arrive; the thumbnail does. And there, there is no political imagination—only a pact with habit.

Deja una respuesta