Scott King’s The New Space arrives as a strange hybrid object: neither quite a book nor a magazine, but a conflation of both. It is glossy, drenched in a vibrant green cover that feels more branding deck than artist’s folio. That is not accidental. Its format situates it squarely inside the cultural economy it purports to critique. The art world today is inseparable from the logic of communications—press packs, campaigns, packages. The New Space looks like the very thing it diagnoses.

Scott King’s The New Space arrives as a strange hybrid object: neither quite a book nor a magazine. It feels more branding deck than artist’s folio. It squarely situates inside the cultural economy it purports to critique.

Tweet

Open it and one encounters a sequence of enumerated mandates: one declaration per page, printed in large type, underlined for emphasis. At first sight this could be concrete poetry—aphoristic phrases whose arrangement on the page constitutes their meaning. But it is also a solitary manifesto, written in the voice of someone with no collective to address, no crowd to summon. If a manifesto calls a public into being, this one stages the absence of such a public. The text reads like a KPI list written by a culture worker lost in the bureaucracy of his own ambition.

“Their Space” and the Binary of English Art

Point 1 sets the tone: “The accumulation of Their Space is my only goal.” The underlining matters. “Space” here is not property but visibility: gallery slots, press mentions, panel invitations, feeds, pixels. More about time than space. And it is theirs—allocated by institutions, rationed by platforms. In England, the identity “artist” is not neutral. It comes with a binary: either submit to the mandates of the market (galleries, fairs, collectors, or their digital twins on Instagram), or become an illustrator—an image supplier for other people’s messages. King is one of those. Both routes are conditioned by networking: the endless labour of circulation, dinners, intros, mutuals.

In England, the identity “artist” is not neutral. It comes with a binary: either submit to the mandates of the market or become an illustrator—an image supplier for other people’s messages. King is one of those. Market or market. No escape from and endless labour of circulation.

Tweet

In that sense, King’s manifesto is not melodramatic but diagnostic. He condenses the soft power of British cultural life—its boards, clubs, and committees—into a single metric: “Their Space.” And he confesses dependence. Point 6 admits: “As my Spatial Allocation has decreased—my identity has come under threat.” Visibility is tied to identity itself. To be unseen is not simply to be out of work but to be undone as an artist. Point 7 clarifies: “Their Space” is not property but presence—“The thought of being rendered Invisible haunts me.” Invisibility is not natural absence but an act inflicted, a verdict of non-recognition.

This is the patriarchal mandate reframed as career management: expand, accumulate, conquer. Failure to accumulate is feminised as weakness. Retreat is pathologised as burnout. King knows it. Hence the fantasy of exit.

Diogenes with Wi-Fi

Point 8 introduces that fantasy: a Total Retreat. A hut, a field, by the sea. Flat horizons, no plinths. King plays Diogenes: withdrawal as critique. But he cannot escape relationality. His practice is communicative; he has always worked through messages and circulation. So he does what every retreating artist does in 2025: he reconnects to Wi-Fi.

He announces his withdrawal online. The paradox is immediate. The act of leaving the system becomes a post to the system. And the system rewards it. He gets traction. Withdrawal circulates as content. Even boredom becomes productive. Neurosis, in solitude, turns to obsession.

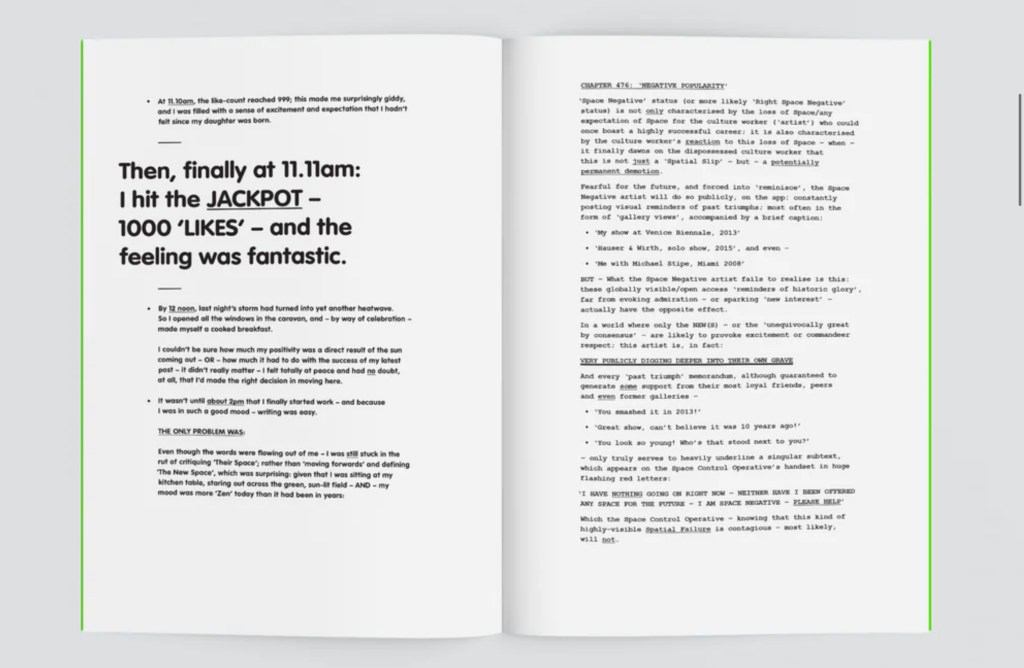

Here the satire sharpens. King resurrects an old Excel sheet he once used to track likes, ranking them according to the status of the liker. At the top: “famous culture workers with strong multiple connections to the Right Space: important institutions, publications, brands, or similar.” At the bottom: “non-famous personal friends, immediate family, random low-ranking strangers, the majority of graphic designers, fake accounts.” He labels the bottom tier Invisible. Everyone knows this hierarchy; no one says it out loud. King literalises it.

And then the miracle: the director of a major museum likes his post. Not his work, not his show, but his Diogenes lifestyle. Retreat itself becomes brand asset. The attempt to escape Space Control returns as premium allocation from its apex. This is not just comic. It is tragic. Even refusal is metabolised. Even boredom is monetised. Even invisibility is reabsorbed as content.

Addiction, Approval, and Emergency Posts

Point 12: “I cannot ignore the fact that my mood has dipped.” Mood underlined, quantified. The elation of recognition gives way to the comedown. Approval functions like a drug: bursts of dopamine followed by withdrawal symptoms. Networking is addiction. Relationality itself is the substance.

King writes himself a Post-It: “You must eliminate your desire to win their approval.” But the compulsion persists. He considers an “emergency covering post” just to remind the world I AM STILL HERE. The absurdity is clear: even horrors in the world fail to register because he is devastated by the news that a designer friend made it into “The 100 Greatest Album Covers of the 1990s. Thank you designmuseumgent.” The structure is the same: elation, collapse, withdrawal, relapse. Addiction is the allegory of the book.

In Scott King’s The New Space, approval functions like a drug: bursts of dopamine followed by withdrawal symptoms. Networking is addiction. Relationality itself is… the substance.

Tweet

Letter of Resignation and the Global South

Faced with the inauthenticity of staging outsiderhood, King pivots. The caravan itself, he realises, would be content. So the only authentic gesture left is a Letter of Resignation. Not a Happening, not a retreat, not a manifesto. A resignation letter refuses the grammar of inclusion altogether.

And here, belatedly, the Global South enters. King’s exercise is remescent of the Instituto Di Tella in 1960s Buenos Aires, where Pop and Happenings flourished under developmentalist democracy, only to be interrupted by General Onganía’s coup in 1966. Philosopher Gregorio Klimovsky condemned Happenings as immoral in a time of imperialist war. And Pablo Suárez, after participating in Tucumán Arde (1968)—a dematerialised action that exposed media manipulation—concluded that if art wants to be political, it cannot be art. The institution itself is governance. Space Control avant la lettre.

King’s resignation echoes this, but only as parody. Unlike Suárez, he cannot escape the loop of self-consciousness. His resignation will be published, archived, liked. Refusal becomes content.

The Global South matters here because refusal was not a lifestyle brand but survival. In Argentina, critique meant censorship, disappearance, exile. Against that backdrop, King’s Diogenes-in-a-caravan reads as symptom: a belated parody of critique in a country where the stakes are gentrification, not dictatorship.

Class Comedy and the Petrol Garage

Point 14: the petrol garage. Hopperesque scene. The man behind the counter wants to chat. King is too busy feeding or resisting Space Control. The counter becomes frontier. The man has “a strong accent” and “always refers to them or what they say.” Epiphany: “THE WINDOW IS A CINEMA SCREEN AND HE IS THE AUDIENCE. HE STANDS HERE ALL DAY, EVERY DAY, AND THIS SCREEN HAS BECOME HIS WHOLE LIFE.”

But is this Diogenes realising withdrawal fails unless it turns monastic? Or is it just class caricature, English vernacular inferiority dressed up as allegory? The joke is cruel: the provincial attendant reduced to foil for the artist’s revelation. But the reversal is obvious: what if the attendant is the audience and King is the spectacle? A middle-aged man in a sweaty caravan, addicted to likes, staging withdrawal as theatre. The petrol worker sees through the play.

Seriousness as Authenticity

King discovers seriousness as currency. In today’s art-academic circuit, seriousness equals authenticity. Frivolity risks cancellation. To package yourself as serious is to guarantee safety.

So he resolves: his resignation letter must look familiar and must be serious. He starts with Chomsky, then adds Mark Fisher, Chris Kraus, Ariana Reines, even mis-cites Deleuze. He calls this “glue-heavy.” He’s right. Citations here do not argue; they accumulate. Seriousness is achieved by proximity: Fisher plus Kraus plus Reines equals depth.

King discovers seriousness as currency. In today’s art-academic circuit, seriousness equals authenticity. Frivolity risks cancellation. To package yourself as serious is to guarantee safety.

Tweet

At this point, the resentment turns inward. The critique is no longer against Space Control but against himself, against his own limitations. The midlife crisis becomes English derision. Since the YBAs, self-pity has been aestheticised into privilege: the embarrassment of riches converted into conceptual art.

The Inquisition and the Cross

Point 15: “This is taking forever.” Boredom sets in. At the bottom of the page, an Adorno quote: “The categorical imperative of the culture industry no longer has anything in common with freedom.” But King writes it as a note-to-self: include this later. Belief or gesture?

This recalls the sixteenth-century Spanish mystics. Their visions happened, but only within prayer. Outside, under the Inquisition, they didn’t really happen. They were always suspect. King’s revelations are similar: they happen inside the fable, but disavowed as comedy, they never fully happen outside.

The analogy is not innocent. What the Inquisition did to mystical speech, Space Control does to critique. It polices the conditions under which anything can be said. To survive, mystics veiled their truths in allegory. King does the same. Hyperbole becomes safeguard. He introduces a concrete poem in the form of a cross, with surreal references to psychosis and rubber masks. Here the humour falters. What was satire of visibility becomes parody of mental illness. But the form betrays the truth: the confessional mode is theological. King has staged his own auto-da-fé.

Class, Masculinity, and the Far Right

Then come the jokes about trousers and make-up. “Unsure if my black t-shirt and suit trousers will be too ordinary.” This is inverted classism: ridiculing those who “try too hard,” the provincial outsider. But this is not harmless. As I write, 110,000 followers of Tommy Robinson gather in central London, cheering Elon Musk, clashing with police. Britain is tilting to the far right. Mocking the ordinary is part of the same politics of exclusion.

This is not abstract for me. For two years I have lived a judiciary purgatory where, as the victim of an attack, I was transubstantiated into the perpetrator. What I suffered were hate crimes, fuelled by homophobia and xenophobia, laundered through institutions. In that context, King’s anxieties about black trousers or wearing make-up—“It might add something, make my image seem less obviously MALE… a bit more ‘now’”—feel hollow. For him, gender performance is costume. For many, it is survival.

Gentrification and England’s Ordinariness

King admits: “A friend sold his business for £10M. He was wealthy before.” Later: “I owned once a house now worth £1.2M. Now I am in a caravan.” This is not revolution. This is gentrification. The very cultural industry he longs for thrived by inflating property values, displacing communities, feeding the bubble. Now the bubble bursts. England is forced to face its own ordinariness.

King aestheticises the fall from house-owner to caravan-dweller as if it were Cynic philosophy reborn. But what it really registers is the embarrassment of privilege in a country that no longer knows how to believe in its own exceptionalism.

Rock Bottom, Redemption, Relapse

Point 16 changes aesthetics. Fonts shrink to the type of an Olivetti, as if authenticity could be typed into being. He erases the app, meditates, narrates insignificance. Redemption at last. But then he goes to a pub. Empty but for a cleaner, who talks too much, about water distribution. King cannot listen. He misses cultivated peers. He blames the cleaner for his relapse. He returns to the caravan and downloads the app again. The cycle repeats.

Conclusion: The Ordinariness of England

What is The New Space? It is comedy that doesn’t always land, institutional critique that arrives too late, and a parody of midlife crisis dressed in Deleuze. But it is also diagnostic. It reveals the structure of cultural life in England today: visibility as allocation, networking as addiction, refusal as content, seriousness as packaging, class contempt as humour.

King wanted a Letter of Resignation, but what he produced was a ledger of neurosis. That, too, is telling. In a Britain where the far right rallies, where property bubbles burst, where hate crimes transubstantiate victims into perpetrators, The New Space is less a critique of Space Control than a chronicle of ordinariness. England, like King, confronts the embarrassment of its own decline, aestheticised as self-deprecating humour.

Scott king’s the new space: una alegoria De la adiccion de un artista por permanecer visible en el mundo del arte

The New Space de Scott King llega como un objeto extraño: ni del todo libro ni del todo revista, sino una fusión de ambos. Es brillante, con una tapa verde vibrante que se siente más como un manual de marca que como un portfolio artístico. Y eso no es casual. Su formato lo sitúa de lleno dentro de la economía cultural que pretende criticar. El arte contemporáneo hoy es inseparable de la lógica de la comunicación: dossiers de prensa, campañas, presentaciones. The New Space parece justamente aquello que diagnostica.

The New Space de Scott King llega como un objeto extraño: ni del todo libro ni del todo revista, sino una fusión de ambos. Su formato lo sitúa de lleno dentro de la economía cultural que pretende criticar.

Tweet

Al abrirlo uno se encuentra con una serie de mandatos numerados: una declaración por página, en tipografía grande, subrayada para enfatizar. A primera vista podría ser poesía concreta —aforismos cuya disposición en la página constituye su significado—. Pero también es un manifiesto en soledad, escrito en la voz de alguien que no tiene un colectivo al cual convocar. Si el manifiesto llama a un público a existir, este manifiesto escenifica la ausencia de tal público. El texto suena como una lista de objetivos redactada por un trabajador cultural perdido en la burocracia de su propia ambición.

“Su Espacio” y la disyuntiva del arte inglés

El Punto 1 marca el tono: “La acumulación de Su Espacio es mi único objetivo.” El subrayado importa. “Espacio” aquí no es propiedad sino visibilidad: lugares en galerías, menciones en la prensa, invitaciones a paneles, píxeles en redes. Y es suyo: asignado por instituciones, racionado por plataformas. En Inglaterra, la identidad de “artista” no es neutra. Conlleva una disyuntiva: o someterse a los mandatos del mercado (galerías, ferias, coleccionistas, o sus gemelos digitales en Instagram), o convertirse en ilustrador —un proveedor de imágenes para los mensajes de otros—. Ambos caminos están condicionados por el networking: la interminable labor de circular, cenar, intercambiar contactos, acumular “mutuals”.

En ese sentido, el manifiesto de King no es melodramático sino diagnóstico. Condensa el poder blando de la vida cultural británica —sus consejos, clubes y comités— en una sola variable: “Su Espacio”. Y confiesa dependencia. El Punto 6 admite: “A medida que mi Asignación de Espacio ha disminuido, mi identidad se ha visto amenazada.” La visibilidad se liga a la identidad misma. No ser visto no es solo estar sin trabajo: es dejar de ser artista. El Punto 7 lo clarifica: “Su Espacio” no es propiedad sino presencia: “El pensamiento de ser vuelto Invisible me atormenta.” La invisibilidad no es ausencia natural sino un acto infligido, un veredicto de no-reconocimiento.

Este es el mandato patriarcal reformulado como gestión de carrera: expandirse, acumular, conquistar. El fracaso en acumular se feminiza como debilidad. La retirada se patologiza como burnout. King lo sabe. De ahí la fantasía de fuga.

Diógenes con Wi-Fi

El Punto 8 introduce esa fantasía: un Retiro Total. Una choza, un campo, el mar. Horizontes planos, sin pedestales. King juega a Diógenes: el retiro como crítica. Pero no puede escapar de la relacionalidad. Su práctica es comunicativa; siempre trabajó a través de mensajes y circulación. Así que hace lo que todo artista en fuga hace en 2025: se conecta al Wi-Fi.

Scott anuncia su retiro online. La paradoja es inmediata. El acto de salir del sistema se convierte en un post para el sistema. Y el sistema lo recompensa. Gana likes. La retirada acaba siendo contenido. Hasta el aburrimiento se vuelve productivo. La neurosis, en soledad, se convierte en obsesión.

Scott anuncia su retiro online. La paradoja es inmediata. El acto de salir del sistema se convierte en un post para el sistema. Y el sistema lo recompensa. Hasta el aburrimiento se vuelve productivo

Tweet

Aquí la sátira se afila. King resucita una vieja planilla Excel que usaba para seguir “likes”, jerarquizándolos según el estatus de quien los daba. Arriba: “trabajadores culturales famosos con múltiples conexiones fuertes al Espacio Correcto: instituciones importantes, publicaciones, marcas o similares.” Abajo: “amigos personales no famosos, familia inmediata, extraños de bajo rango, la mayoría de los diseñadores gráficos, cuentas falsas.” A este nivel lo llama Invisible. Todos conocen esta jerarquía; nadie la dice en voz alta. King la literaliza.

Y luego el milagro: el director de un museo importante le da “like”. No a su obra, no a su muestra, sino a su estilo de vida Diógenes. La retirada se convierte en un activo de marca. El intento de escapar del Control del Espacio vuelve como asignación premium desde su cima. Esto no es solo cómico. Es trágico. Incluso la negativa es metabolizada. Incluso el aburrimiento es monetizado. Incluso la invisibilidad se reabsorbe como contenido.

Adicción, aprobación y posts de emergencia

Punto 12: “No puedo ignorar que mi ánimo ha decaído.” Ánimo subrayado, cuantificado. La euforia del reconocimiento da paso a la resaca. La aprobación funciona como droga: estallidos de dopamina seguidos de síntomas de abstinencia. El networking es adicción. La relacionalidad misma es la sustancia.

King se escribe un Post-It: “Debes eliminar tu deseo de ganar su aprobación.” Pero la compulsión persiste. Considera un “post de emergencia” solo para recordarle al mundo QUE SIGO AQUÍ. La absurdidad es evidente: incluso los horrores del mundo no llegan a registrarse porque él está devastado por la noticia de que un amigo diseñador entró en “Las 100 mejores portadas de discos de los 90. Gracias designmuseumgent.” La estructura es la misma: euforia, caída, abstinencia, recaída. La adicción es la alegoría del libro.

Carta de renuncia y el Sur Global

Ante la imposibilidad de representar la exterioridad sin volverla contenido, King entra en loop. La caravana misma, se da cuenta, es su nuevo contenido. Es como si no hubiera escape de este nuevo espacio. Lo único que le queda por hacer es una Carta de Renuncia. No un Happening, no un retiro, no un manifiesto. Una carta de renuncia rechaza la gramática de la inclusión por completo.

Ante la imposibilidad de representar la exterioridad sin volverla contenido, King entra en loop. La caravana misma, se da cuenta, es su nuevo contenido. Es como si no hubiera escape de este nuevo espacio. Lo único que le queda por hacer es una Carta de Renuncia

Tweet

Y aquí, tardíamente, entra el Sur Global. Lo de King recuerda al Instituto Di Tella en el Buenos Aires de los 60, donde el Pop y los Happenings florecieron bajo democracia desarrollista, solo para ser interrumpidos por el golpe del general Onganía en 1966. En realidad, para ser mas especifico, recuerda la reacción del artista Pablo Suarez,tras participar en Tucumán Arde (1968) —acción desmaterializada que expuso la manipulación mediática— concluyó que si el arte quiere ser político, no puede ser arte. El filósofo Gregorio Klimovsky había condenado los Happenings como inmorales en tiempos de guerra imperialista. El Control del Espacio, avant la lettre.

La renuncia de King lo evoca, pero solo como parodia. A diferencia de Suárez, él no puede escapar del bucle de la autoconciencia. Su renuncia será publicada, archivada, “likeada”. La negativa se vuelve contenido. El Sur Global importa porque allí la negativa no fue un estilo de vida sino una estrategia de supervivencia. En Argentina, la crítica significaba censura, desaparición, exilio. En ese contexto, el Diógenes en caravana de King suena como síntoma: una parodia tardía de la crítica en un país donde la disputa es la gentrificación, no la dictadura.

Comedia de clase y la gasolinera

Punto 14: la gasolinera. Escena hopperiana. El hombre tras el mostrador quiere charlar. King está demasiado ocupado alimentando o resistiendo al Control del Espacio. El mostrador se convierte en frontera entre el Narciso y la vida real. El problema es que la vida real, el hombre tras la caja registradora tiene “un fuerte acento” y “siempre se refiere lo que los otros dicen”. Epifanía: “LA VENTANA ES UNA PANTALLA DE CINE Y ÉL ES EL PÚBLICO. ESTÁ AQUÍ TODO EL DÍA, TODOS LOS DÍAS, Y ESTA PANTALLA SE HA VUELTO TODA SU VIDA.”

¿Es esta la conciencia de que el retiro dioquénico fracasa salvo que se vuelva monacal? ¿O es simplemente caricatura de clase, inferioridad vernácula inglesa disfrazada de alegoría? La broma es cruel: el trabajador reducido a telón de fondo de la revelación del artista. Pero la inversión es obvia: ¿y si el público es él, y King el espectáculo? Un hombre de mediana edad en una caravana sudorosa, adicto a los “likes”, representando su retiro como teatro. El trabajador ve a través de la farsa.

La seriedad como autenticidad

King descubre que la seriedad es lo que el mundo del arte exige y acepta. En el circuito arte-academia, ser serio equivale a ser auténtico. La frivolidad arriesga la cancelación. Pero qué es ser serio? Ser “serio” es empacarse como seguro.

Así que resuelve: su carta de renuncia debe parecer familiar y debe ser seria. Empieza con Chomsky, agrega a Mark Fisher, Chris Kraus, Ariana Reines, hasta cita mal a Deleuze. Llama a esto “pegamento pesado”. Y tiene razón. Aquí las citas no argumentan; se acumulan. La seriedad se logra por proximidad: Fisher + Kraus + Reines = profundidad.

En este punto, el resentimiento se vuelve hacia adentro. La crítica ya no es contra el Control del Espacio sino contra sí mismo, contra sus propias limitaciones. La crisis de la mediana edad se vuelve burla inglesa. Desde los YBA, la autocompasión se estetiza como privilegio: la vergüenza de la riqueza convertida en arte conceptual.

En el circuito arte-academia, ser serio equivale a ser auténtico. La frivolidad arriesga la cancelación. Pero qué es ser serio? Ser “serio” es empacarse como seguro.

Tweet

La Inquisición y la cruz

Punto 15: “Esto está llevando una eternidad.” El aburrimiento se instala. Al pie de página, una cita de Adorno: “El imperativo categórico de la industria cultural ya no tiene nada en común con la libertad.” Pero King la escribe como nota: incluir más tarde. ¿Convicción o gesto estetizante ?

Esto recuerda a los místicos españoles del XVI. Sus visiones ocurrían, pero solo dentro de la oración. Fuera, bajo la Inquisición, no ocurrían del todo. Siempre bajo sospecha. Las revelaciones de King son similares: ocurren dentro de la fábula, pero, al ser desmentidas como comedia, nunca ocurren del todo fuera.

Al pie de página, una cita de Adorno: “El imperativo categórico de la industria cultural ya no tiene nada en común con la libertad.” Pero King la escribe como nota: incluir más tarde. ¿Convicción o gesto estetizante ?

Tweet

La analogía no es inocente. Lo que la Inquisición hizo con el discurso místico, el Control del Espacio lo hace con la crítica. Regula las condiciones de lo decible. Para sobrevivir, los místicos velaban sus verdades en alegorías. King hace lo mismo. La hipérbole se vuelve salvavidas. Introduce un poema concreto en forma de cruz, con referencias a psicosis y máscaras de goma. Aquí el humor falla. Lo que era sátira de la visibilidad deviene parodia de enfermedad mental. Pero la forma lo delata: el modo confesional es teológico. King ha escenificado su propio auto de fe.

Clase, masculinidad y la extrema derecha

Luego las bromas sobre pantalones y maquillaje. “No estoy seguro si mi remera negra y mis pantalones de traje serán demasiado ordinarios.” Esto es clasismo invertido: ridiculizar a quienes “se esfuerzan demasiado”, al provinciano. Pero no es inofensivo. En el momento en que escribo, 110.000 seguidores de Tommy Robinson se congregan en el centro de Londres, aclamando a Elon Musk y enfrentándose a la policía. Gran Bretaña se inclina hacia la extrema derecha. Burlarse de lo “ordinario” forma parte de esa política de exclusión.

Para mí esto no es abstracto. Durante dos años viví un purgatorio judicial donde, siendo víctima de un ataque, fui transubstanciado en perpetrador. Lo que sufrí fueron crímenes de odio, alimentados por homofobia y xenofobia, blanqueados por instituciones. En ese contexto, las ansiedades de King sobre pantalones negros o sobre maquillarse —“Podría añadir algo, hacer que mi imagen pareciera menos obviamente MASCULINA… un poco más ‘actual’”— suenan huecas. Para él, el género es disfraz. Para muchos, es supervivencia.

Gentrificación y la ordinariez de Inglaterra

King admite: “Un amigo vendió su negocio por £10M. Ya era rico antes.” Más tarde: “Una vez tuve una casa que ahora vale £1,2M. Ahora vivo en una caravana.” Esto no es revolución. Esto es gentrificación. La misma industria cultural que ansía lo alimentó, inflando valores inmobiliarios, desplazando comunidades, alimentando la burbuja. Ahora la burbuja estalla. Inglaterra debe afrontar su ordinariez.

King admite: “Una vez tuve una casa que ahora vale £1,2M. Ahora vivo en una caravana.” Esto no es revolución. Esto es gentrificación. La misma industria cultural que ansía lo alimentó. Ahora la burbuja estalla. Inglaterra debe afrontar su ordinariez.

Tweet

King estetiza la caída de propietario a habitante de caravana como si fuera filosofía cínica renacida. Pero lo que realmente registra es la vergüenza del privilegio en un país que ya no sabe cómo creer en su propio excepcionalismo.

Tocar fondo, redención, recaída

Punto 16 cambia la estética. Las fuentes se achican, parecen de una Olivetti, como si la autenticidad pudiera teclearse. Borra la app, medita, narra su insignificancia. Redención, al fin. Pero luego va al pub. Vacío salvo por un limpiador, que habla demasiado, sobre la distribución de agua. King no logra escuchar. Extraña a sus pares cultivados. Culpa al limpiador de su recaída. Vuelve a la caravana y descarga la app de nuevo. El ciclo se repite.

Conclusión: la ordinariez de Inglaterra

¿Qué es The New Space? Es comedia que no siempre funciona, crítica institucional llegada demasiado tarde y parodia de crisis de mediana edad vestida de Deleuze. Pero también es diagnóstico. Revela la estructura de la vida cultural inglesa hoy: visibilidad como asignación, networking como adicción, negativa como contenido, seriedad como packaging, desprecio de clase como humor.

King quiso una Carta de Renuncia, pero lo que produjo fue un balance de neurosis. Eso, también, es revelador. En una Gran Bretaña donde la extrema derecha se reúne, donde las burbujas inmobiliarias revientan, donde los crímenes de odio transubstancian a víctimas en culpables, The New Space es menos una crítica del Control del Espacio que una crónica de ordinariez. Inglaterra, como King, enfrenta la vergüenza de su propio declive, estilizado como humor auto despreciativo.

Deja una respuesta