Scroll Back for the English Version

La iglesia de Saint Giles Cripplegate no tiene nada de espectacular. Blanca, pelada, protestante, con ese aire de templo que sobrevive más por obstinación patrimonial que por fe. En medio del Barbican —ese conjunto brutalista que quiso ser utopía y terminó museo del futuro fallido— el silencio tiene otra textura: no es devoción, es conservación patrimonial lo que es muy lindo pero para nada lo mismo. La acústica allí es de piedra desnuda: reverberación suficientemente larga como para envolver el timbre del chelo (sobre todo en las frecuencias medias y graves), pero lo bastante nítida como para que los ataques del arco y los armónicos salten con filo. Es un sitio donde cualquier decisión de presión de arco, punto de contacto (sul tasto/sul ponticello) y vibrato se vuelve declaración estética.

El problema de este país y no me refiero al Reino Unido sino a Inglaterra es lo que el gran Chileno Patricio Marchand llamaba ‘la cosa’ y yo llamo ‘los sistemas’. Este un país enamorado con la producción saturante, incluso para ellos mismos, de sistemas con los cual asfixian y se asfixian.

Tweet

Fui de casualidad. Ben está en LA. Yo tenía ganas de escuchar un buen concierto y la otra opción era la claustrofóbica octava sinfonia de Shostakovich, a la que me invitó Johnny, por lo que no lo dude. Me fui solo a escuchar al cellista Seth Parker. A mi, desde hace un par de años, Inglaterra me mata de manera lenta y meticulosa. No sé si es literal lo que digo pero, por ahora, se siente así. Desde ya, no me refiero ni al lugar ni a su gente o tal vez, un poco si a su gente que hace un cultivo un tanto excesivo de la miserabilidad propia y la infelicidad ajena. El problema de este país y no me refiero al Reino Unido sino a Inglaterra es lo que el gran Chileno Patricio Marchand llamaba ‘la cosa’ y yo llamo ‘los sistemas’. Este un país enamorado con la producción saturante, incluso para ellos mismos, de sistemas con los cual asfixian y se asfixian. Así, cuando las instituciones se tropiezan, les salta la xenofobia o, mejor dicho, la inseguridad por perder el status imperial y buscan un adversario (eso es lo que aprendió Laclau y casi inconscientemente lo transformo en teoría) y nada mejor que un argentino para cagar a palos o violar si se lo tiene inconsciente. Pero con lo que no cuentan es que el argentino no es un ente inerte sino pensante y tal vez, inteligente e incluso mas que ellos. El tema es que me transformaron de victima que fui a sub-humano invisible y de mudo a expediente judicial. El problema con esto es que demanda que uno sea realmente estupido o analfabeto; ademas de muchas mentiras dichas bajo juramento y las mentiras en materia judicial son un boomerang que, tarde o temprano, devienen delito. Para borrarla, alargaron el proceso y aplicaron una estrategia de desestabilización coordinada interinstitucionalmente en la que con dos excepciones, todos me abandonaron. Desde hace meses, la policía, el sistema de salud y la diplomacia argentina hicieron de mí un caso legal olvidándose que antes que nada, yo había sido un caso clínico por un ataque no investigado de acuerdo a protocolos garantizados por ley inglesa y tratados internacionales en donde la culpa, en ultima instancia, recae sobre el ‘sistema’. Y así sufrí dos ataques mas: una amenaza de muerte y un sin fin de ninguneo de mi Consulado, pidiendo protección. Hasta que mi cama amaneció llena de sangre y yo sin entender que había pasado. Ya había conocido durante mi cancelación, el poder de silenciamiento del poder pero, como en aquel caso, al hacerlo se tiran un tiro en el pie porque es como el yudo. Uno termina usando la fuerza ajena a favor de uno. Un argentino que pide ayuda se convierte, sin saberlo, en un problema de relaciones públicas. Y ahí empieza la traducción: de víctima a sospechoso, de ciudadano a paciente, de persona a síntoma. Pero las relaciones publicas se convierten en una queja que pone en cuestión el sistema muy fácilmente y yo diría que casi a la fuerza esa es mi trabajo cultural hoy. Marcar la metamorfosis de lo humano en subhumano y de la mentira en ley. Usar esa fuerza negativa que me llega para transformarla en algo que ayude a prevenir estas cosas y convengamos que todo esto ocurrió bajo un gobierno laborista.

El resultado fue una cadena de malentendidos tan graves que ya no se pueden llamar errores. Me negaron atención médica cuando la necesitaba, me etiquetaron con diagnósticos contradictorios, me dejaron sin medicación de HIV, pretendieron borrar una posible violación tras ser burundageado y esto, la Fiscalía misma. Ya no es un tema legal sino de derechos humanos. Cada paso que di buscando protección generó otra capa de burocracia, otro informe que me congelaba un poco más dentro del sistema. Y todo increíblemente sincronizado. Nunca sabre si lo estuvo. Pero, el zorro ya es viejo y desarrolla anticuerpos y los ve venir de lejos y se prepara. Con eso no contaron.

Me negaron atención médica cuando la necesitaba, me etiquetaron con diagnósticos contradictorios, me dejaron sin medicación de HIV, pretendieron borrar una posible violación tras ser burundageado y esto, la Fiscalía misma. Ya no es un tema legal sino de derechos humanos.

Tweet

Todo eso por una razón tan simple y tan brutal que apenas se nombra: la xenofobia que viene en diferentes paquetes y que, durante años yo había tomado como halago. Es odio empaquetado como halago o, incluso broma. Está la educada y la no educada. No es odio explícito, sino el prejuicio envuelto en cortesía. Esa idea paternalista de que el latino —el “argentinito”— no entiende cómo funcionan las cosas, que hay que explicarle, corregirlo, o simplemente dejarlo esperar hasta que se canse y diga a que es culpable porque se supone que es débil. I mean… Y después están los supuestos amigos que aprovechan tu momento de fragilidad y como el cancer, se acercan para sacarte plata, como, quien apareciera originalmente en el blog como la madama de Barrio Parque: Mariana Marx. Pero de esa rata ya voy a hablar en detalle.

Mientras tanto, en Inglaterra los mismos organismos que me ignoraban producían documentos donde mi confusión se volvía evidencia. Así se fabrica un diagnóstico. Así se produce un trauma tras otro. Vivo con CPTSD, un estado que no deseo a nadie. Es un cuerpo que no distingue entre pasado y presente, que responde con pánico a lo invisible. Londres, con su arquitectura del control, se volvió el escenario perfecto para esa condición: cada carta oficial, cada llamada institucional, cada correo sin respuesta, puede ser un disparador. Una risa en la calle puede disparar un ataque de pánico.

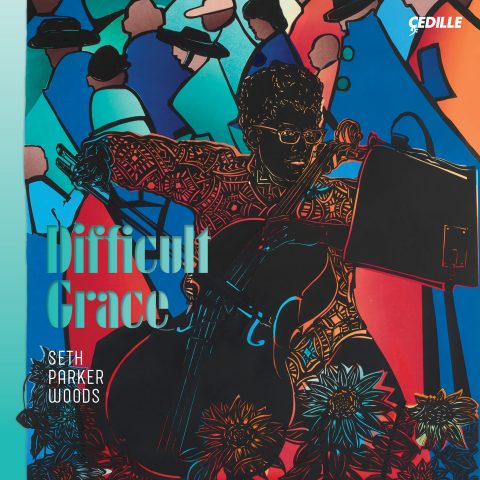

Por eso fui al Barbican. No para escuchar música, sino para respirar un poco. Fui buscando melodía. Llegado el momento del concierto nadie presentó al músico. No hubo el ritual de aplausos ni de títulos honoríficos. No se leyó su curriculum, ni se preparo al publico. Solo se le dio el espacio. Apareció un hombre vestido con telas africanas, con un PhD, con varias nominaciones al Grammy y un cello. Seth Parker Woods —chelista, performer, doctor en Performance por la Universidad de Huddersfield (West Yorkshire)— apareció sin palabras, sin refugio, como quien va a ejecutar un conjuro y vaya que lo hizo. Me agarro desprevenido. El formato del programa —Bach como columna vertebral intercalado con voces del siglo XX y XXI, afro-diaspóricas y asiáticas— ya era un manifiesto curatorial: canon/contracanon, archivo/ritual.

Por eso fui al Barbican. No para escuchar música, sino para respirar un poco. Fui buscando melodía. Llegado el momento del concierto nadie presentó al músico. Solo se le dio el espacio. Apareció un hombre vestido con telas africanas, con un PhD, con varias nominaciones al Grammy y un cello. Seth Parker Woods me agarro desprevenido.

Tweet

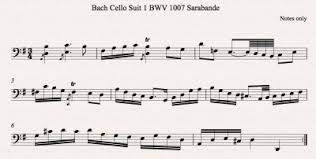

Comenzó con fragmentos de la Sarabande de Bach (Suite No. 1, BWV 1007). Tocó como al pasar, sin pathos, sin esa teatralidad sentimental que los intérpretes suelen usar para demostrar profundidad. Sonaba arqueológico: el canon barroco reducido a su esqueleto. No era frialdad; era una operación crítica. Usaba su virtuosismo para describir un cadaver. Y aca hay que prestar atención porque como yo soy argentino pero no tengo un pelo de boludo, Parker Woods es afroamericano pero cada inserción es una estrategia conceptual que funciona como operación en el espacio publico de carácter politico, La elección de la Sarabande no es casual. La tocó con un arco muy controlado, vibrato mínimo, dejando que las dobles cuerdas respiren sin retórica; cuando desplazaba el punto de contacto hacia el puente (sul ponticello leve), emergía un brillo casi calcáreo, como si exhibiera la osamenta armónica del movimiento. En Saint Giles, esa desnudez se expande: la resonancia de la nave redondea los finales de frase, y el silencio posterior queda cargado, más significante que cualquier rubato romántico.

Comenzó con fragmentos de la Sarabande de Bach (Suite No. 1, BWV 1007). Tocó como al pasar, sin pathos, sin esa teatralidad sentimental que los intérpretes suelen usar para demostrar profundidad. Sonaba arqueológico: el canon barroco reducido a su esqueleto. No era frialdad; era una operación crítica.

Tweet

La Sarabande —danza lenta de origen afro-latino, nacida como zarabanda y prohibida en España por “obscena”— fue blanqueada por Francia y Alemania hasta volverse rezo cortesano. Woods la interpretaba sin ornamentación, como quien muestra el hueso de un santo para recordar que también se pudre. Un hueso que, en realidad, es una alegoria de violencia sexual colonial. En su arco apareció una arqueología del sonido colonial para un público anciano, blanco y demasiado nostálgicamente inglés para entender la sofisticación de la operación. Incluso en los retornos a Bach (más adelante volvería a la Sarabande de otras suites), mantuvo esa ética de “museo sonoro”: bordaduras contenidas, fraseo recto, articulaciones secas donde otros buscan lágrimas.

Al instante, entendí que el concierto no trataba de Bach, sino de cómo se manipuló y pretende seguir manipulándose al fantasma de Bach. Bach es un canon que sobrevive porque fue limpiado de deseo y cuerpo. Y ahi me vino a la mente un recuerdo en el British Museum, con mi ex, el Bahiano. Él, que nunca había salido de su Bahía natal, me escuchaba recitar la genealogía del mundo frente a las vitrinas del imperio. Yo haciendo gala de la educación logrado en la metropolis y el, muy poco impresionado y hasta ofendido. En un momento, mirando los bronces de Benin, dijo: “Todo esto está robado”. Yo veía universalidad; él veía botín. El museo, en el mejor de los casos, es apenas la forma elegante del saqueo. En el peor es una compilación de muerte y salvajismo.

Algo pareciodo pasó en Saint Giles, esta noche. El público londinense escuchaba a Woods tratando de reconocer algo que ya no puede reconocer, como su país. Lo que sonaba ya no era música sino arqueología del canon. La Sarabande se volvió metáfora: una danza negra convertida en plegaria blanca.

El público londinense escuchaba a Woods tratando de reconocer algo que ya no puede reconocer, como su país. Lo que sonaba ya no era música sino arqueología del canon. La Sarabande se volvió metáfora: una danza negra convertida en plegaria blanca.

Tweet

¿Qué hacer con Bach?

Entre Sarabande y Sarabande algo mutó. Cuando Woods abandonaba a Bach y se adentraba en piezas donde él mismo había intervenido —como Dam Mwen de la haitiana Nathalie Joachim— el cello se encendía. Ya no era un objeto ilustrado: era un cuerpo que respiraba. Dam Mwen significa, según el contexto, “mi mujer”, “mi alma” o “mi casa”. En la interpretación de Woods esa ambigüedad se volvía pertenencia sonora. El instrumento hablaba en creol. El aire cambiaba de densidad: si Bach era museo, Joachim era ritual. Se notó en la paleta tímbrica: alternó sul tasto ancho (el arco cerca del diapasón, sonido aterciopelado) con acentos casi percusivos que sugerían palma y tambor; insinuó patrones de llamada-y-respuesta dentro del propio instrumento, como si el chelo fuera dos voces. La pieza —que proviene del universo de Fanm d’Ayiti— trae el pulso del canto haitiano y Woods lo deja entrar al templo sin pedir permiso.

Cuando Woods abandonaba a Bach y se adentraba en piezas donde él mismo había intervenido —como Dam Mwen de la haitiana Nathalie Joachim— el cello se encendía. Ya no era un objeto ilustrado: era un cuerpo que respiraba y hablaba en creol.

Tweet

El público, sin embargo, no sabía qué hacer con eso. Se movían en las butacas, miradas espasmicas al programa. La incomodidad era casi táctil. La música era demasiado emotiva para la contención protestante y demasiado intelectual para el sentimentalismo clásico. Les devolvía una imagen que no querían ver: la de su propio límite. En esa tensión me reconocí. Yo también soy, para esta Inglaterra, un significante flotante. No encajo en la narrativa del refugiado ni en la del culpable; no represento una minoría que se pueda celebrar sin riesgo. Soy mestizo, latino, queer, lúcido, y por eso indigerible. Ellos tampoco saben qué hacer conmigo.

Experimente la disociación frente a las autoridades británicas. Durante el concierto, not pun intended pero lo que reino fue el desconcierto. Para mi funciono como un espejo: Woods hacía sonar la fractura, y todos —educadamente sentados— nos veíamos reflejados en ella.

La disociación como forma de conciencia

Con las obras de Fredrick Gifford y Alvin Singleton, el recital cambió de estado. Lo electrónico no era adorno sino desdoblamiento. Cada nota encontraba su eco digital, cada impulso su sombra. El cello se volvió enjambre, cuerpo expandido, materia en tránsito. En Gifford, la electrónica (live) funcionaba como cámara de espejos: pequeños retardos y capas granulares que devolvían al chelo con otras edades; escuchabas el ataque crudo y, milisegundos después, su fantasma. Woods explotó armónicos naturales, glissandi de mano izquierda y sobrepresión controlada del arco para forzar rugosidades (scratch tones) que, al ser reinyectadas por los altavoces, parecían otra especie de chelo.

Con las obras de Fredrick Gifford y Alvin Singleton, el recital cambió de estado. Lo electrónico no era adorno sino desdoblamiento. Cada nota encontraba su eco digital, cada impulso su sombra. El cello se volvió cámara de espejos

Tweet

No era atonal, era esquizoide, pero no en el sentido clínico de la ruptura sino en el político de la multiplicidad. El sonido era muchos a la vez: un cuerpo atravesado por historias, géneros y memorias que no caben en la unidad. Singleton empujó en otra dirección: escritura incantatoria, silencios que pesan, células rítmicas que vuelven como mantra; una espiritualidad seca, sin azúcar sinfónica, donde el swing es recuerdo y el rezo es pulso. Y pensé en mi propia desintegración física e identitaria frente al avance sistémico de esta metrópolis que ya no se reconoce a sí misma. Lo que para mí fue trauma, Woods lo convertía en método. Transformaba la disociación en conciencia. Cada repetición, cada eco, cada ruido parecía decir que lo roto también puede ser conocimiento. En su gesto había dignidad, no nostalgia. El sonido no buscaba curar sino habitar la fractura.

El límite del oído occidental

Entre pieza y pieza, Woods hablaba. En Inglaterra eso se considera una falta de decoro: el intérprete no debe contaminar la pureza de la música con su biografía. Pero sus comentarios —que en cualquier otro sonarían autorreferenciales— se volvían aceptables bajo el sello Barbican. El sistema cultural británico domestica la diferencia: la convierte en subversión curada. Ser un hombre negro le otorga, además, un tipo de legitimidad que el liberalismo blanco adora: la del “otro autorizado”. El público progresista necesita esos cuerpos para confirmar su propia tolerancia. Yo no tengo ese salvoconducto: soy latino, híbrido, un tipo de alteridad que el sistema no sabe archivar.

Pero la segunda parte del concierto borró toda etiqueta. Con Khse Buon de Chinary Ung, el lenguaje se volvió irreconocible. La melodía occidental se deshizo en microtonos, el tiempo en respiración. Era la música del otro lado del espejo. Ung escribe como quien devuelve al instrumento su condición de voz no temperada: glissandi que no “buscan” nota sino que habitan el entre-nota, armónicos que aparecen y se van como sombras, golpes de arco (a veces quasi col legno) que rompen la línea y la vuelven percusión. Saint Giles amplifica esa inestabilidad: los microdesajustes se quedan flotando y te obligan a escuchar el aire entre un tono y otro.

Grand Tour

Pensé en Grand Tour, la película de Miguel Gomes que había visto la noche anterior en MUBI. En ella, un diplomático británico recorre la Asia colonial intentando escapar de su prometida y de sí mismo. En cierto momento confiesa: “Los occidentales nunca podremos comprender a Oriente.” Esa frase, dicha en 1917 por un hombre que huye de todo, resume el fracaso histórico del imperio: viajar sin entender, clasificar sin escuchar. La obra de Ung le pone sonido a esa imposibilidad. No traduce ni explica; deja al oyente suspendido, sin suelo, como un funcionario colonial sin mapa. El público inglés, que había sobrevivido con Bach, quedó allí expuesto: enfrentado a un idioma que no se ofrece a su desciframiento.

El sonido en loop del trauma

El final fue con Julius Eastman. Su Joan of Arc (más precisamente, The Holy Presence of Joan d’Arc, 1981, originalmente para diez cellos; aquí en versión/condensación para chelo y electrónica) convirtió la iglesia en un panal de abejas. Un enjambre sonoro que avanzaba en oleadas, entre la geometría y el delirio. Una gestalt vibrante, un loop del trauma. La pieza se arma con ostinati que se superponen por capas: patrones de arco en presión media-alta, trémolos que se compactan hasta parecer motor, y repeticiones que no son “la misma cosa” sino un insistir que cambia el aire. La electrónica le da el grosor de coro: escuchás “muchos cellos” cuando hay uno solo.

Eastman, negro, queer, expulsado del canon, murió en la pobreza mientras la academia que lo ignoró ahora lo eleva a mártir. Woods lo revivía sin sentimentalismo, con una potencia casi terapéutica: el trauma vuelto estructura. Cada repetición era un intento de recordar lo que no puede recordarse; cada vibración, una forma de hacer del dolor un sistema. Era hasta gracioso verlo hacer eso frente a los ingleses. Los mismos que veneran la contención escuchaban la furia organizada del cuerpo queer racializado. Eastman devolvía el golpe: la barbarie era su música, y la civilización, su desconcierto. En esa inversión se condensaba todo: el imperio reducido a un murmullo perplejo, la iglesia protestante convertida en laboratorio del cuerpo, la música descolonizando el oído en tiempo real.

Salí de la iglesia con una mezcla de vértigo y alivio. Londres seguía siendo la maquinaria que clasifica y diagnostica, pero durante una hora y pico el sonido había abierto una grieta y qué es lo vida sino una sucesión de grietas. Allí donde las instituciones me fallaron —la policía, el sistema de salud, la diplomacia— encontré algo parecido a reparación: no justicia, pero sí un modo de respirar distinto. En la música de Woods, el trauma se volvió lenguaje; la disociación, método; la extranjería, gramática.

Y comprendí algo simple: la conciencia no siempre nace de la calma. A veces solo emerge cuando el ruido deja de ser enemigo y se vuelve ritmo. El ritmo y el ruido es como la belleza, el loco, el excéntrico, etc. Depende quien lo defina.

Classical Music That Reverses the Relation Between Civilization and Barbarism: Seth Parker Woods and the Cello as Ghost

Decolonising with the Body the Neo-Colonial

Saint Giles Cripplegate Church is nothing spectacular. White, bare, Protestant—one of those temples that survive more out of patrimonial obstinacy than faith. In the middle of the Barbican — that brutalist complex that wanted to be utopia and ended up a museum of a failed future — silence has a different texture: not devotion, but conservation. Beautiful, but not the same thing. Its acoustics are stone-pure: enough reverberation to wrap the cello’s middle and low registers, yet dry enough to expose every bow attack and harmonic. In that space, every pressure, every sul tasto or sul ponticello, every shimmer of vibrato becomes a statement.

Ben, my love interest is filming in L.A. I did not have much to do and felt like listening to a good concert. The other option was Shostakovich’s claustrophobic Eighth Symphony, which my friend Johnny had invited me to, so I didn’t hesitate: I said no. Instead, I went alone to hear the cellist Seth Parker Woods.

Tweet

I went by chance. Ben, my love interest is filming in L.A. I did not have much to do and felt like listening to a good concert. The other option was Shostakovich’s claustrophobic Eighth Symphony, which my friend Johnny had invited me to, so I didn’t hesitate: I said no. Instead, I went alone to hear the cellist Seth Parker Woods. For the last couple of years, England has been killing me slowly and methodically. I don’t know if that’s literally true, but for now, it feels that way. I don’t mean the place itself, nor even its people—or perhaps, a little, its people too, who cultivate their own misery and others’ unhappiness with almost aesthetic devotion. The problem with this country—and I mean England, not the United Kingdom—is what the great Chilean Patricio Marchand once called the thing, and what I call the systems. This is a nation in love with the suffocating overproduction of systems—with building them, enforcing them, and ultimately choking on them. So when institutions stumble, their insecurity leaks out: a kind of refined xenophobia, or rather, the fear of losing imperial status. They look for an adversary (something Laclau understood and, almost unconsciously, turned into theory), and there’s nothing better than an Argentine to beat up—or to rape—if he’s unconscious. The Falklands, Maradona, the Hand of God, the Nazis… so many reasons to find an Argentine turn from friend into enemy, in seconds.

What does systemic forms of Herrshaft, since we mentioned the Nazis, do not count on, however, is that the Argentine is, in principle, not inert but could think back—and perhaps those thoughts may end up being more elaborate than previously thought, maybe even more so than they are. The problem is that they turned me, the victim of crime back then in January 2024, into something subhuman and increasingly invisible. Someone who passed from voiceless to judicial case file. The difficulty with trusting that this “systemic”, let’s call it, Neo-Colonial strategy to work is that it requires the (hate the word) “victim” to be truly stupid or illiterate. Besides the serial production of so many lies told under oath is always problematic—and lies in legal matters are a boomerang that sooner or later become crimes in themselves. Whether they became human rights crimes or common law crimes depends on the position of the State in front of that very abstract value called Justice.

To erase those lies, the System prolonged the process and applied a coordinated inter-institutional destabilisation strategy in which, with two exceptions, everyone abandoned me. But do not feel sorry for me, so quickly. Not yet. For months now, the police and the health system have made a legal case out of me, forgetting that I was first and foremost a clinical case—after an attack never investigated according to procedures guaranteed by English law. The one to blame for that is, ultimately: “the system.”

I warned all parties involved because one is not Minister of Culture of his country for no reason. There must be some strategy buried in my spirit. As expected, I suffered two more attacks (one of them very recent), a death threat, and an endless series of dismissals and silences from my own Consulate, even as I begged for protection—until one morning I woke up to find my bed full of blood, with no idea what had happened the night before. I had already learned, during my so-called cancellation in my country which, since that time, was preparing to be sold. In that occasion, it shocked me how power silences—but like in judo, it ends up shooting itself in the foot. You end up using its own force against it. An Argentine who asks for help becomes, without knowing it, a public-relations problem. And that’s where the translation begins: from victim to suspect, from citizen to patient, from person to symptom.

But public relations easily turn into complaint, and complaints expose systems. I would say that, almost by necessity, that has become my cultural work today: tracing the metamorphosis of the human into the subhuman, and of lies into law. Using that negative force aimed at me to transform it into something that might help prevent such things from happening again—and let’s be clear: all this happened under a Labour government. The result has been a chain of misunderstandings so grave they can no longer be called errors. I was denied medical care when I needed it, labeled with contradictory diagnoses, left without medication or response. Every step toward protection created another bureaucratic layer, another report freezing me deeper inside the system. All eerily synchronized, even if it wasn’t. I’ll never know. But the fox is old now; he’s grown antibodies, sees them coming from afar, prepares.

All this for a reason so simple and brutal it barely gets named: xenophobia in its various packages—the educated kind and the raw kind. Not open hatred, but prejudice wrapped in courtesy. That paternal idea that the Latin — the little Argentinian — doesn’t understand how things work, must be corrected, or simply left to wait until he gives up. Meanwhile, the very institutions that ignored me produced documents turning my confusion into evidence. That’s how you manufacture a diagnosis. That’s how you produce trauma upon trauma. I live with CPTSD, a state I wouldn’t wish on anyone: a body that can’t tell past from present, that responds to the invisible with panic. London, with its architecture of control, became the perfect stage for that condition: every official letter, every unanswered email, every street laugh can trigger a collapse.

What Does Seth Parker Wood Have To Do With This?

That’s why I went to the Barbican. Not to hear music, but to breathe. I went in search of melody, of a space where sound wasn’t attached to a form to fill. When the concert began, no one introduced the performer. No ritual of applause or honorary titles. No curriculum read aloud, no program notes to guide the audience. Just a man in African fabrics, with a PhD, multiple Grammy nominations, and a cello. Seth Parker Woods — cellist, performer, Doctor of Performance from the University of Huddersfield (West Yorkshire) — appeared without words, without refuge, as if to cast a spell. And he did. It caught me off guard.

When the concert began, no one introduced the performer. No ritual of applause or honorary titles. No curriculum read aloud, no program notes to guide the audience. Just a man in African fabrics, with a PhD, multiple Grammy nominations, and a cello.

Tweet

The program itself—Bach as spine, interwoven with twentieth- and twenty-first-century Afro-diasporic and Asian voices—was already a curatorial manifesto: canon versus counter-canon, archive versus ritual. He began with fragments of Bach’s Sarabande (Suite No. 1, BWV 1007). He played them as if passing by, without pathos, without that sentimental theatre performers use to prove depth. It sounded archaeological: the Baroque canon reduced to its skeleton. It wasn’t coldness; it was a critical operation. He used virtuosity to describe a corpse.

Parker Woods began with Bach’s Sarabande (Suite No. 1, BWV 1007). He played them as if passing by, without pathos, without that sentimental theatre performers use to prove depth. It sounded archaeological: the Baroque canon reduced to its skeleton. He used virtuosity to describe a corpse.

Tweet

The Sarabande—a slow dance of Afro-Latin origin, born as the zarabanda and banned in Spain for being “obscene”—was later whitened by France and Germany into a courtly prayer. Woods played it stripped bare, as if showing the saint’s bone to remind us it also rots. In his bow there appeared an archaeology of colonial sound for an elderly, white, nostalgically English audience too self-satisfied to grasp the sophistication of the gesture.

In Parker’s bow there appeared an archaeology of colonial sound for an elderly, white, nostalgically English audience too self-satisfied to grasp the sophistication of the gesture.

Tweet

He kept the bow tight, vibrato minimal, double-stops breathing without rhetoric. When he edged toward the bridge (a faint sul ponticello), a chalky brilliance surfaced—as if exposing the harmonic skeleton of the movement. In Saint Giles, that nakedness expands; the nave’s resonance rounds the line endings, and the silence that follows is charged, more eloquent than any Romantic rubato.

In that instant I understood the concert wasn’t about Bach but about how Bach’s ghost has been manipulated, embalmed, and made to haunt us. Bach is a canon that survives because it was scrubbed clean of desire and body. A memory hit me from the British Museum with my ex, the Bahian. He’d never left his native Bahia, and there I was reciting the genealogy of the world in front of the empire’s vitrines. I played the metropolitan pedagogue; he, unimpressed and almost offended. Staring at the Benin Bronzes, he said: “All of this is stolen.” I saw universality; he saw loot. The museum, at best, is the elegant form of theft. At worst, a compendium of death and savagery.

Something similar happened in Saint Giles that night. The London audience listened to Woods trying to recognize something they could no longer recognize—like their own country. What sounded wasn’t music but the archaeology of the canon. The Sarabande became a metaphor: a Black dance turned white prayer.

What to do with Bach?

Between Sarabandes something shifted. When Woods left Bach behind and entered works he’d helped create—like Dam Mwen by the Haitian-American Nathalie Joachim—the cello ignited. It stopped being an illustrated object and became a breathing body. Dam Mwen means “my woman,” “my soul,” or “my home,” depending on context. In Woods’s performance that ambiguity became a form of sonic belonging. The instrument spoke Creole. The air thickened: if Bach was museum, Joachim was ritual.

Between Sarabandes something shifted. When Woods left Bach behind and entered works he’d helped create—like Dam Mwen by the Haitian-American Nathalie Joachim—the cello ignited. It stopped being an illustrated object and became a breathing body.

Tweet

You could hear it in timbre: broad sul tasto for a velvet tone, interrupted by almost percussive accents suggesting palm and drum. Call-and-response patterns seemed to form within the instrument itself, as if it were two voices. The piece, from the world of Fanm d’Ayiti, carries the pulse of Haitian song, and Woods let it enter the church without asking permission.

The audience didn’t know what to do. They shifted in their seats, flicked at their programs, nervous. The discomfort was almost tactile. The music was too emotional for Protestant restraint, too intellectual for classical sentimentality. It mirrored back an image they didn’t want to see: their own limit. In that tension I recognized myself. I too am, for this England, a floating signifier. I don’t fit the refugee narrative or the guilty one; I’m not a minority that can be safely celebrated. I’m mestizo, Latin, queer, lucid—therefore indigestible. They don’t know what to do with me either.

I’ve experienced dissociation in front of British authorities. During the concert, no pun intended, what reigned was disconcertment. For me it worked as a mirror: Woods made the fracture audible, and all of us—politely seated—saw ourselves reflected in it.

I’ve experienced dissociation in front of British authorities. During the concert, no pun intended, what reigned was disconcertment. For me it worked as a mirror: Woods made the fracture audible, and all of us—politely seated—saw ourselves reflected in it.

Tweet

Dissociation as a Form of Consciousness

With the works of Fredrick Gifford and Alvin Singleton, the recital changed state. Electronics were no ornament but duplication. Each note found its digital echo, each impulse its shadow. The cello became swarm, expanded body, matter in transit.

In Gifford, the live electronics acted like a hall of mirrors: micro-delays and granular layers returning the cello at different ages. You heard the raw attack and, milliseconds later, its ghost. Woods exploited natural harmonics, left-hand glissandi, and controlled bow pressure to produce rough textures—scratch tones—which, when re-injected through the speakers, sounded like another species of cello. Singleton pushed elsewhere: incantatory writing, heavy silences, rhythmic cells that return like mantras—a dry spirituality, sugarless, where swing is memory and prayer is pulse.

It was not atonal but schizoid—not in the clinical sense of rupture but in the political sense of multiplicity. The sound was many at once: a body crossed by histories, genders, memories that can’t fit into unity. And I thought of my own physical and identity disintegration against this metropolis that no longer recognizes itself. What for me had been trauma, Woods turned into method. He transformed dissociation into consciousness. Each repetition, each echo, each noise seemed to say that what’s broken can also be knowledge. In his gesture there was dignity, not nostalgia. The sound didn’t try to heal; it chose to inhabit the fracture.

The Limit of the Western Ear

Between pieces, Woods spoke. In England, that’s bad manners: the performer must not contaminate the purity of music with biography. But his remarks—elsewhere deemed self-referential—became acceptable under the Barbican’s seal. The British cultural system domesticates difference; it turns it into curated subversion. Being a Black man grants him the kind of legitimacy white liberalism adores: that of the “authorized other.” The progressive audience needs such bodies to reassure itself of its own tolerance. I have no such pass. I’m Latino, hybrid—an alterity the system doesn’t know how to file.

But the second half erased every label. With Khse Buon by Chinary Ung, language itself became unrecognizable. The Western melody dissolved into microtones, time into breath. It was music from the other side of the mirror. Ung writes as if returning the instrument to a pre-tempered voice: glissandi that don’t seek a note but dwell in between, harmonics that flicker and vanish, bow strikes (quasi col legno) breaking the line into percussion. In Saint Giles, those micro-instabilities hover, forcing you to listen to the air between pitches.

With Khse Buon by Chinary Ung, language itself became unrecognizable. The Western melody dissolved into microtones, time into breath. It was music from the other side of the mirror.

Tweet

Grand Tour

I thought of Grand Tour, Miguel Gomes’s 2024 film I’d watched the night before on MUBI. In it, a British diplomat roams colonial Asia, fleeing his fiancée and himself. At one point he confesses: “We Westerners will never be able to understand the East.” That line, uttered in 1917 by a man running from everything, condenses the empire’s historic failure: to travel without understanding, to classify without listening.

Ung’s work gives that impossibility a sound. It doesn’t translate or explain; it leaves the listener suspended, floorless, like a colonial officer without a map. The English audience, which had survived Bach, was left exposed—confronted with a language that refused to be decoded.

The Looped Sound of Trauma

The concert ended with Julius Eastman’s Joan of Arc—more precisely, The Holy Presence of Joan d’Arc (1981), originally for ten cellos, here condensed for cello and electronics. It turned the church into a hive. A sonic swarm moving in waves between geometry and delirium. A vibrating gestalt, a loop of trauma.

The piece builds through layered ostinati: bow patterns under medium-high pressure, tremolos compacted into motor noise, repetitions that aren’t the same but a shifting insistence. Electronics supply the choir’s thickness—you hear many cellos when there is only one. Eastman—Black, queer, expelled from the canon—died in poverty while the academy that ignored him now hails him as martyr. Woods revived him without sentimentality, with almost therapeutic power: trauma turned structure. Each repetition was an attempt to remember what can’t be remembered; each vibration a way of turning pain into system. It was even funny watching him do it before the English. Those who venerate restraint were now listening to the organized fury of the queer, racialized body. Eastman struck back: barbarism was his music, civilization its confusion. In that inversion everything condensed: empire reduced to a perplexed murmur, the Protestant church transformed into a laboratory of the body, music decolonizing the ear in real time.

Epilogue: Breathing

I left the church dizzy but relieved. London remained the same machine of classification and diagnosis, but for an hour the sound had opened a crack. Where institutions had failed me—police, health, diplomacy—I found something like repair: not justice, but a different way of breathing. In Woods’s music, trauma became language; dissociation, method; foreignness, grammar. And I understood something simple: consciousness doesn’t always arise from calm. Sometimes it appears only when noise stops being the enemy and becomes rhythm.

Deja una respuesta